記者/譯者

After Putin's invasion of Ukraine, what should the Russians do?

Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine, I've always wondered: How did the Russians feel about the war?

A recent article by Duan Media answered this question to a certain extent. According to the local first-hand observations of Duan Media’s contributors, Russians seem to have fallen into habitual questioning and information about war-related information. fatigue.

But what I thought after reading it was that in addition to the people in Russia, the Baltic countries (including Estonia, Latvia, and recently Lithuania, which has frequent exchanges with Taiwan) actually have a lot of Russian populations.

Most of these Baltic Russians settled in the Soviet period (the three Baltic countries were also part of the Soviet Union at that time), and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, many Russians chose to stay and acquired the nationality of the Baltic countries.

However, the descendants of these Russian-speaking populations may not be better off in the newly independent countries - they were originally the largest ethnic group in the Soviet Union, but after the independence of the Baltic countries, they turned into "minorities" instead.

In addition, the Russians, as the main ethnic group of the Soviet Union, are sometimes regarded by the "local communities" in the Baltic region as "the incarnation of the Soviet Union", so they still occasionally have tensions with the local communities, and even become the targets of anger.

When I crossed the Eurasian continent and took the train from China to Spain in 2009, I also passed by Estonia and witnessed this kind of post-Soviet era ethnopolitics.

On the day I arrived in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, I was in a square in the city and met several policemen who were pulling up a cordon. The locals told me that two drunk Estonians killed a Russian resident in the square the night before. , adding that "Russians are not welcome here".

However, to this day, the Russian/Russian population still accounts for one-fifth of the total population of Estonia, and the last person I knew in Estonia was a descendant of Russian.

At that time, I was watching the sunset beside the old city wall of Tallinn, but the screws on my glasses came loose. When the man standing next to me saw this, he took out a sewing kit and used simple tools to help me fix my glasses.

So we chatted.

The man I spoke to was named Vitali. He told me that his parents moved to Estonia during the Soviet Union for work; he himself was born in Estonia.

Later, Vitali accompanied me to the bus stop and dropped me off for a ride to Latvia. Before saying goodbye to me, he signed his name on the sewing box and shoved it into my hand, hoping I would always remember him.

Finally I mustered up the courage to ask him, why not go to Russia if the Russian population is so unpopular here? He shook his head and said, "This is my home."

Looking back now, I don't know how Vitali is doing now, and how will he view this war?

More importantly, after Russia invaded Ukraine, it seems that the Baltic countries, including Estonia, have also moved closer to the West. Now that the war is not over, how do the "local communities" in these places deal with these Russian populations?

In addition to Russians in Russia and in the former Soviet Union countries, another article by Duan Media, from the perspective of music, talked about the news that "Russian musicians were asked to express their opinions and choose sides", and borrowed This discussion is a topic: how should we view the statement that "music belongs to music, and politics belongs to politics"?

The author of the article mentioned that in history, music and politics have been difficult to separate completely, and the reason why classical music can touch people's hearts is because "it has an impact on all aspects of life, whether it is love, friendship, politics, war, Hunger, religion, philosophical thinking, etc., all kinds of fears and longings are deeply written into the works, stirring the heartstrings of listeners and making them reflect on life.”

But the author also reminds that we cannot "indiscriminately" ban all Russian musicians, because that would be tantamount to "homogenizing" all Russians.

As listeners and readers, what we can do now is: from now on, try to understand Ukraine as an independent country, its unique culture, and its achievements in classical music, art and culture.

After reading the article, I thought that almost ten years ago, a friend introduced a Russian conductor to me and wanted me to teach him Chinese online.

At that time, I only found out that he wanted to learn Chinese because he had performed in China, wanted to increase his chances of performing in China, and wanted to communicate with Chinese people more. But maybe because his schedule was too busy, I remember that after I taught three or four classes, he disappeared silently.

Later, when I read his posts on Facebook, I realized that he seems to be a little-known musician who not only tours around the world, but also keeps reposting reports about him by various media.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, I paid special attention to his Facebook and found that he has been posting continuously recently, and there are even photos of him performing at the Bolshoi Theater these days, but there is no information related to the Ukraine-Russian war. As if nothing happened.

I can only guess: is he a Putin supporter? Or did he accept official Russian propaganda, and also thought it was a "special operation" and not a war?

But then again, is it possible that a musician like him, who often tours abroad and communicates with the outside world so frequently, is ignorant of the recent situation in Ukraine, as well as the caliber and perception of Western countries' reports on the war?

Or does he also feel that this is just a "political" matter that has nothing to do with him personally or with his favorite classical music? Or is it that he is afraid to express his views on the war simply because he is in Russia?

I don't know either—I haven't figured out how to ask him about it.

Another worthy of attention, and also related to the internal dynamics of Russia, is the characteristics of the composition of soldiers within the Russian army.

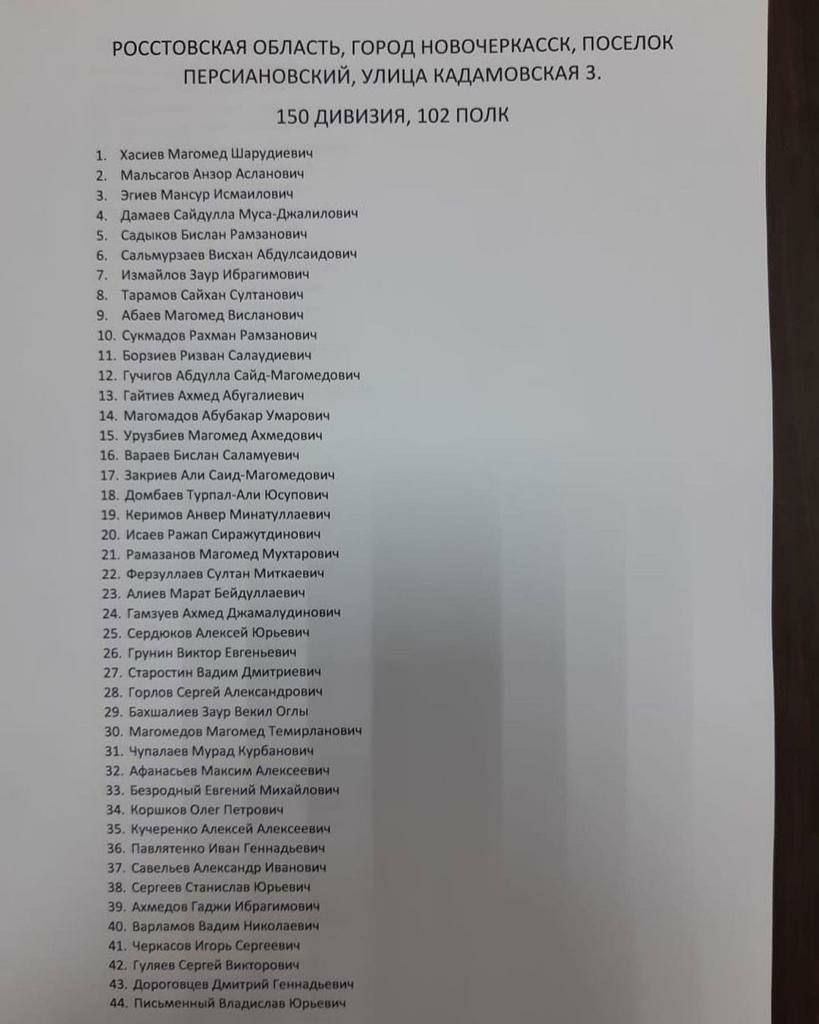

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Russian journalist and scholar Kamil Galeev, who has been very active on Twitter and has attracted the attention of many fans, recently mentioned that the proportion of soldiers of "non-Russian ethnicity" in this invasion of Ukraine was higher than that of these ethnic groups. The proportion of the total population of Russia is even higher - that is, the concept of overrepresented in English (this word, I still don't know how to translate it into Chinese in a simplified way).

Galeev gave an example: in a list of wounded soldiers of the Russian army, many people's first names or surnames were derived from Muhammad, such as Магомед, Магомедович.

If you look closely at the list, you can find many more common Muslim names, such as Абдулла (Abdullah), Ахмед (Ahmed), Рахман (Rahman).

According to Galeev, most of these people are "Dagestani" (Dagestani) from the North Caucasus; they are traditionally devout Muslims, like the neighbouring Chechens.

Galeev points to several reasons for the high percentage of Dagestanis (and other "minorities") in the Russian military.

First, the regions where these "minorities" are located were originally the regions with the highest fertility rates in Russia, so they can provide an abundant supply of young men.

Second, these ethnic groups come from rural areas, where job opportunities are scarce, so military careers are relatively attractive.

In addition, they come from rural areas with poor education and do not know how to avoid conscription; even if they are killed on the front line, their families will only grieve in secret, instead of defending their rights and protesting like urbanites.

But the Muslim names in that list also reminded me of one thing:

The first time I knew that there were a lot of Muslims in Russia was when I was studying Arabic in Kuwait—the language school at that time was filled with Russian students, many of them from the North Caucasus.

Since there were many Muslims from the former Soviet Union countries (such as Kyrgyz and Tajiks) in the language center, the language most often heard by students in language schools at that time, in addition to English, was actually Russian.

Later, I translated a book and learned that during the expansion of the Russian Empire, Dagestan was one of the most violent areas against the Russians, and continued to rise up until the nineteenth century.

However, it is somewhat ironic that, just over a hundred years after the annexation, the Dagestanians have become an important element of the Russian army today, helping the Russians to revive the glory of the nation.

But then again, the disproportionate number of "ethnic minorities" serving as professional soldiers is not unique to Russia. When I was in the army more than ten years ago, I also discovered that a high percentage of volunteers are indigenous people. .

I remember one time, a sergeant told me jokingly that when the old communists called, it was us aboriginal people who wanted to help you on the battlefield, but it was obviously a war between you Han people, and it was none of our aboriginal people’s business ( To the effect) …

But somewhat surprisingly, the Ukrainian war also drew news , bringing an interesting new case to the "enclave" issue I've been tracking.

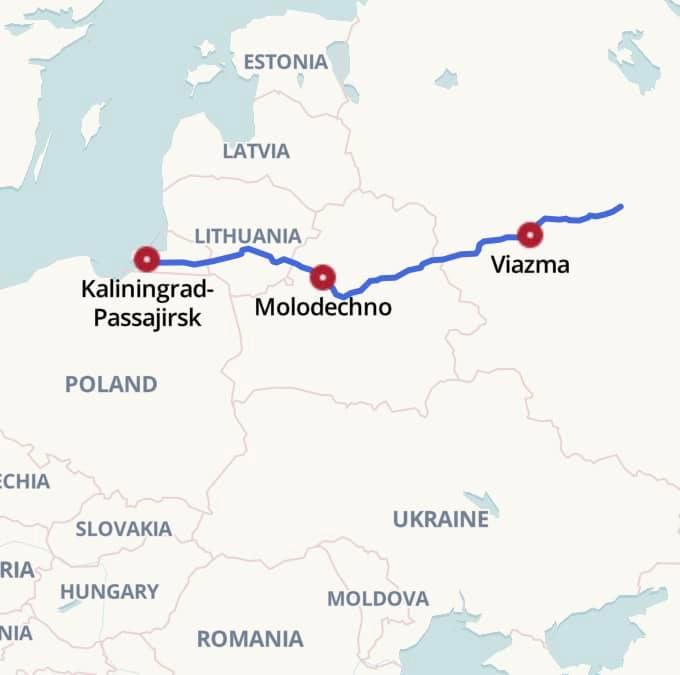

Here's the thing: Russia has an enclave territory called Kaliningrad on the Baltic Sea between Poland and Lithuania. This place was originally German territory (Kant's hometown is here), named Königsberg, but after Germany's defeat in World War II, it was assigned to the Soviet Union and attached to Russia.

Although Lithuania and Belarus are still separated from this territory and the Russian mainland, this was not a problem at all in the Soviet era—because Lithuania and Belarus are also part of the Soviet Union, so there is no cross-border The problem.

However, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the independence of Lithuania and Belarus, the problem became bigger: if you don't take a plane, you have to take a train from Russia to Kaliningrad, which is bound to pass through Lithuania and Belarus.

It doesn't matter to Belarus, after all, Russia and Belarus are related, and for a long time after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were no border checks between the two countries - but Lithuania is different. They are solidly independent and later It also joined the Schengen area.

So Russia and Lithuania made an agreement so that trains from Russia to Kaliningrad could pass through Lithuanian territory.

Unexpectedly, this arrangement because of the enclave had an unexpected purpose during the Ukrainian-Russian War.

To stop the Russians from being fooled by the state media and telling them about the damage caused by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Lithuanian Railways Agency set up 24 signboards on the platforms of the capital’s station with bombed apartments in Ukraine, Photos of displaced people.

Ten minutes after the train stopped, there was a Russian broadcast on the platform: "Dear passenger, Putin is killing Ukrainian civilians. Do you support this?"

Meanwhile, there's another, also rail-related news today: Finland is ending the St. Petersburg-Helsinki rail service -- a railroad that the Russians have escaped from while Russia is sanctioned and almost blocked to foreign traffic. One of the last few routes in the country.

It's also interesting to think about.

Because of the characteristics of being "surrounded by other countries' territory and separated from the mother country", enclaves are often very closed and difficult to access. Unexpectedly, at the moment of the Ukrainian-Russian war, Russia has almost turned itself into the world's largest "enclave". ”, isolated from the whole world.

As for the home country of this new "enclave"? It may be Putin and his supporters, the resurgent but still non-existent "Great Russia" in their minds.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…