connect the dots.

The complicated history of Soviet computer science

Subtitle: How did computers get revenge on the Soviet Union? Computers denounced as tools of capitalism exposed the weakness of the Soviet Union.

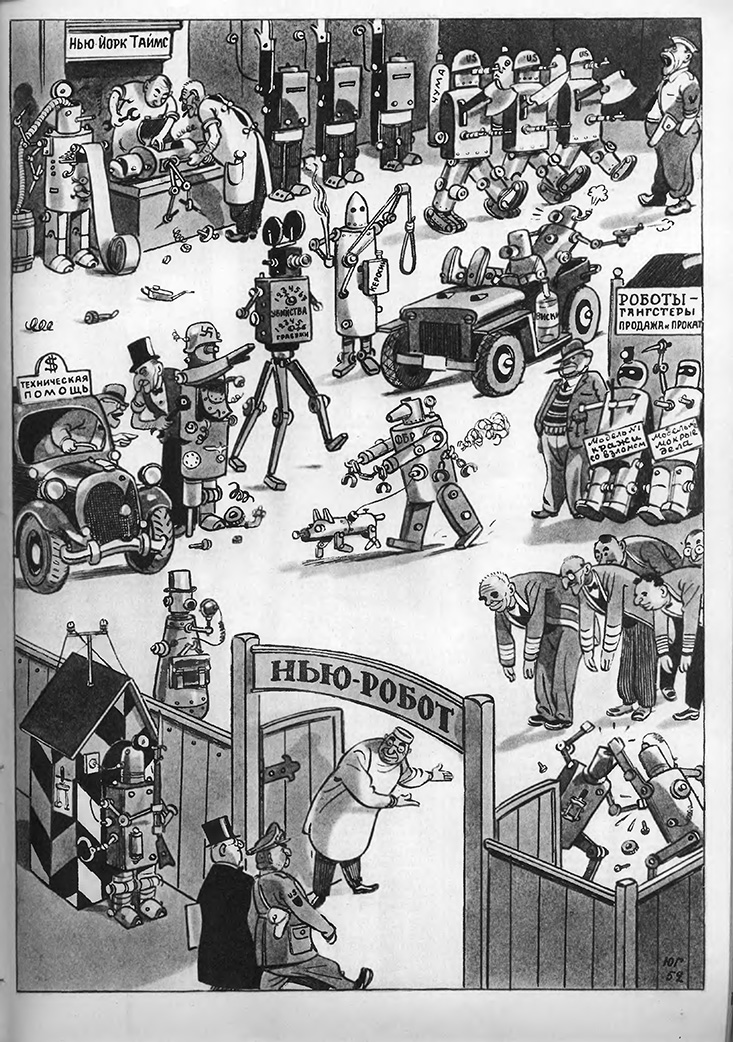

In 1950, with the Cold War in full swing, Soviet journalists were desperately looking for something to help them with their anti-American propaganda mission. In January of that year, a Time magazine cover seemed to offer just that. It showed an early electromechanical computer, called the Harvard Mark III, and featured on the cover: "Can Man Build a Superman?"

This is a goal that meets ideological standards. In May 1950, Boris Agapov, the science editor of the Soviet Literary Gazette, wrote a dismissive commentary on the American public's fascination with "thinking machines." He mocked the capitalist "sweet dream" of replacing class-conscious workers and human soldiers with submissive robots. He scoffed at the idea of using computers to process economic information, and quipped that American businessmen "love information [like] American patients love patented pills." He scorned the Western prophets of the information age, especially the most famous of them—the creator of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener, a professor of mathematics at MIT. Cybernetics, which was only a few years old at the time, claimed that the mechanisms of control and communication in biology, technology, and society were fundamentally the same. Of course, Boris Agapov hadn't actually read Wiener's book Cybernetics on the subject; the content of his article makes it clear that all he knew about cybernetics was from January Borrowed from the 23rd issue of Time magazine, and likely borrowed from its cover image.

In the paranoid Soviet media environment, Boris Agapov's article was seen as a signal from above. The psychologist Mikhail Iaroshevskii picked up on the implication and published two sharp attacks on cybernetics, one in the Literary Gazette and the other in the Literary Gazette. One was published in a 1951 collection of essays entitled "Against The philosophing Henchmen of American and English Imperialism". He accused Wiener of reducing human thought to formalized operations, and called cybernetics a "fashionable pseudo-theory" fabricated by "ignorants hostile to humans and science." He goes on to quote Wiener's famous statement that the computer revolution "bound to devalue the human brain" just as the industrial revolution devalued human labor. While Wiener meant that his comments were a liberal critique of capitalism and called for "a society based on human values other than buying and selling", Miha Mikhail Iaroshevskii apparently interprets it as a cynical deviance. "From this wonderful idea," he wrote, "(semanticists-cannibals) concluded that the greater part of mankind must be exterminated." Like Boris Agapov, Mikhail I Mikhail Iaroshevskii also did not read any of Wiener's writings. In fact, it wasn't easy: Wiener's cybernetics were removed from the Soviet library after Boris Agapov's attack. Instead, Mikhail Iaroshevskii draws his views mainly from Boris Agapov's earlier articles.

When one critic repeats the accusations of another critic, repeating old accusations, and fabricating new ones, an anti-cybernetics movement unites. Critics didn't stop them from being ignorant of what cybernetics actually was about -- in fact, it helped unleash their imaginations. They deftly manipulated some Wiener quotes out of context, putting cybernetic cloak on an ideological scarecrow. Wiener's statement that "information is information, not matter or energy" (information is information, not matter or energy) has been exaggerated, and it has become "nothing to do with matter or consciousness" (nothing to do with matter or consciousness). ), critics concluded that cybernetics was moving along a "straight path to open idealism and religion" (both terms were derogatory terms in the Soviet Union, of course).

Philosophers also joined in, attacking cybernetics as "clinging to the remnants of old idealistic philosophy" and "mechanisms" that reduce the activity of the human brain to "mechanical connections and signals." Cybernetics, they claim, is doubly guilty. It departed from dialectical materialism, the official Soviet philosophy of science, and went in two opposite directions at the same time—idealism and mechanism. The media portrayed it as "idealistic" and "mechanistic", "utopian" and "dystopian", "technocratic" and "pessimistic" ( pessimistic), "pseudo-science", is a dangerous weapon of Western military aggression. Critics of the Soviet Union ignored, or perhaps did not realize, Wiener's public pacifist stance after the Hiroshima bombing, and his refusal to engage in military research.

Of course, the trouble with these overt attacks on computer use is that the country desperately needs computers. The military in particular recognizes the value of this emerging technology, as well as the risk of falling behind.

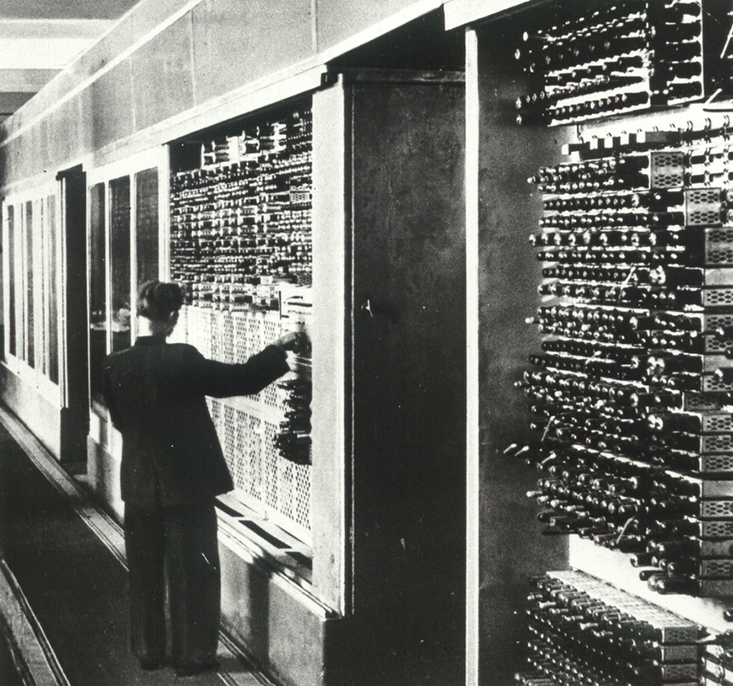

Thus, in a classic example of "two-facedness", the Soviet Union began to secretly pursue military calculations while condemning the West for doing so. While the media mocked the Americans' "fantasy" of giving military orders to robots, Sergei Sobolev, the chief mathematician of the Soviet nuclear weapons program, worked tirelessly to develop new computers. These included the Soviet Union's first computer, the MESM, and its first minicomputer, the M-1.

In January 1950, the Soviet Union even launched a capitalist-style competition between two competing projects, the same month that Time magazine ran its famous cover. The task of each top-secret project is to build large, high-speed electronic computers for military computing. One of them, called BESM, was developed by the Academy of Sciences of the USSR; the other, called Strela, was developed by the Ministry of Machine Building and Instrumentation. Both institutions devoted enormous resources to these flagship projects, and in 1954, Strela was declared the winner. Seven of the massive, room-sized machines were produced and put into military use, helping to design hydrogen bombs, nuclear strike efficiency simulations, missile defense system design, and various naval and air force projects. An improved version of the BESM became the fastest computer in Europe and soon went into production as well. Computer experts verbally supported the anti-cybernetic movement at their political education conferences and then began to develop new military control and communication systems based on cybernetic principles.

Using computers requires special care: any questionable cybernetic terminology must be avoided. Even the phrase "logical operations" is dangerous, as it could be interpreted to imply that machines can think. The researchers used the more neutral technical term "storage" instead of "computer memory", "information" was replaced by "data", and "information theory" ) was replaced by the puzzling expression "the statistical theory of electrical signal transmission with noise". A joke about Stalin's man, Beria, who was in charge of the nuclear weapons program, became popular. Beria approached his boss and asked for permission to use the notorious cybernetic realm for military purposes. Stalin, blowing his pipe, said, "Okay, but make sure other Politburo members don't find out."

By 1953, Soviet cybernetics had been snubbed for three years. In March of that year, Stalin died, and five months later, the Soviet Union tested its first thermonuclear device (the United States also tested theirs two years earlier), and the Soviet Union's fortunes finally began to turn around. Scientists and engineers, encouraged by the reputation their military work had earned, began fighting back against Stalin-backed ideologues and party literati. Disciplines that were suppressed under Stalin, such as genetics and mathematical economics, began to return to universities and research laboratories. Scientists and computer experts began to advocate a similar revival of cybernetics. In August 1955, the journal Problems of Philosophy, which published a scathing critique of cybernetics, suddenly changed its stance, like a weathervane sensing the changing direction of the wind. It published a landmark article in support of the discipline called The Main Features of Cybernetics.

The article, signed by three heavyweights from the military computing field, refuted all ideological accusations of cybernetics. Instead of trying to reconcile it with dialectical materialism, the author simply states that it is valid and therefore must be ideologically correct. They read Wiener's work in the classified section of the Military Research Library, and they synthesized the Soviet version of cybernetics, drawing its legitimacy from the practical value of computer technology.

The article inspired cybernetic enthusiasts to push computers into all areas of the civilian economy—from transportation and industrial automation, to weather forecasting and economic planning. The regime's ideological platitudes are back again, but this time in support of this emerging field. The researchers began publishing an annual book series called Cybernetics in the Service of Communism, highlighting the bright future of computers helping to build a new society.

Party leaders were quickly persuaded, and the 1961 Communist Party program stated that cybernetics was essential to the building of communism. The government issued a series of resolutions authorizing the construction of new computer factories, and the mass media began touting computers as "communist machines." The word "cybernetics" was removed from the blacklist and became a trendy nickname. Genetics is now "biological cybernetics," non-Pavlovian physiology is "physiological cybernetics," and mathematical economics is "economic cybernetics." It helped replace the simplistic Pavlovian conditioning scheme based on the telephone switchboard analogy, with a more complex model that likened the brain to an information processor. Even the law turns its attention to "judicial cybernetics"; legal scholars dream of having their concepts "as exact as [those] of mathematics, physics, and chemistry ). Soviet computers have been restarted.

The cybernetic agenda in economics and management is particularly bold. The researchers proposed to link all Soviet enterprises through a unified national computer network, so as to process economic information in real time and optimize the entire economy. The proposal raised serious alarm among CIA analysts, who began to suspect that cybernetics had grown too powerful in the hands of the Soviet government. They attracted the attention of the Kennedy administration, and in October 1962, President Kennedy's special assistant, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., pessimistically predicted in a memo that "the full Soviet commitment to cybernetics "would give the Soviet Union a "great advantage". Schlesinger warned that "by 1970 the Soviet Union may have an entirely new production technology involving entire enterprises or industrial complexes governed by closed-loop feedback control using self-learning computers." A special group of experts was established to investigate the Soviet Union cybernetic threat.

What Schlesinger may not have realized is the extent to which the Soviet authorities used cybernetics to maintain their administrative hierarchy and resist reform. In the 1970s, the Soviet government launched a massive campaign to introduce computerized management systems into the economy for production control and planning, but without fundamentally changing management structures or the balance of power.

This turned out to be a serious mistake. The Soviet centrally planned economy was ill-prepared for computerization. Its cumbersome bureaucracy is too slow to implement rapid changes in production and distribution, and it is ruled by ministries of industry that, like separate fiefdoms, are reluctant to share their information or decision-making power. Therefore, each ministry has established its own information management system, which is disconnected and incompatible with other departments. Instead of turning a top-down economic system into a self-regulating system, the bureaucrats used their new cybernetic models and computers to protect their power. Expensive and largely useless information management systems are scattered across the country.

The results of top-down computerization are devastating. New computer systems accumulate ever-increasing amounts of raw data, producing a horrific mountain of paperwork. In the early 1970s, approximately 4 billion documents circulated in the Soviet economy every year. By the mid-1980s, following a major push to computerize the bureaucracy, that number had risen 200-fold to some 800 billion documents, the equivalent of 3,000 documents per Soviet citizen. All of this information still has to pass through centralized, hierarchically assigned narrow channels, squeezed by institutional barriers and secrecy restrictions. Management has become very unwieldy. For example, in order to obtain a license to produce common flat iron, a factory manager must collect more than 60 signatures. Technological innovation has become a bureaucratic nightmare.

Big Brother wants to see everything and know everything, but is inundated with distorted information from lower-level officials trying to paint a better picture. A flood of inaccurate information paralyzes decision-making mechanisms, while accurate information can only be exchanged locally, like black market merchandise or banned books in samizdat. Computers were once vilified and now championed, but one thing remains the same: they magnify the advantages and disadvantages of the systems that implement them. After all, the key idea behind cybernetics is control through feedback. In the hands of self-motivated free agents, it is a powerful economic engine. In the hands of a single controlling agency, it brings stagnation. Or, as computer scientists like to say, "garbage in, garbage out." Originally intended to prove the superiority of socialism, information technology ultimately proved the incompetence of the Soviet regime.

Soviet humour is an irony. As a joke goes, Brezhnev had the latest artificial intelligence, so he asked, "When will we build communism?" The computer responded, "Within 17 miles." Brezhnev thought , "There must be something wrong", and repeated the question. The computer replied again, "Within 17 miles." Enraged by the incomprehensible answer, Brezhnev ordered a technician to investigate the machine. "Everything is fine," the technician replied after a while. "You said it yourself: every five-year plan is a step toward communism."

The author, Slava Gerovitch, is a lecturer in the history of mathematics and director of the research program at MIT. He is an expert on the history of Russian science and technology and is the author of From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics and two books on Soviet space exploration.

Compiled from: An article on the Nautilus website How the Computer Got Its Revenge on the Soviet Union

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…