【社會觀察×教育評論】台灣的台語(閩南語)發展 The Development of Taiwanese Hokkien (Taiyu)

1. 台語在台灣弱化的原因

The reasons for the decline of Taiwanese Hokkien in Taiwan

台灣的台語,過去曾為中華民國政府推廣的地方漢語方言。第二次世界大戰日本戰敗,日本曾經從清朝割地的殖民地台灣,在1945年後藉由美軍給中華民國政府託管。而被日本殖民的台灣,已經轉變為高識字率的地區,因此中華民國國民黨政府1946年延續當年1896年日本殖民台灣推廣國語用平片假名拼閩南語的方案,推廣用閩南語去學習中文。

然而國民黨的蔣中正與共產黨毛澤東爭奪中國政權失敗後,蔣中正計畫將台灣成為反攻大陸的基地,並在美國制衡蘇俄策略下,接受美國的援助。專制的蔣中正政權為了避免台灣本土知識份子參與或反對政治統治,也為了增加其他中國其他省份與台灣本土居民的隔閡、避免台灣本土人士往統治階層流動,因此國民黨執政的中華民國政府開始了消滅母語運動。若是講母語(主要是閩南語)、不講中文,在學校就會罰錢。幾十年下來,戰後嬰兒潮的世代已經越來越不會講母語。

Taiwanese Hokkien, a local Chinese dialect, was once promoted by the government of the Republic of China. After Japan's defeat in World War II, Taiwan, which had been ceded by the Qing dynasty and colonized by Japan, was placed under the administration of the Republic of China by the U.S. military in 1945. During Japan's colonization, Taiwan had developed into a region with a high literacy rate. Building on Japan's earlier efforts from 1896 to promote the use of the national language (using simplified phonetic katakana to teach Hokkien), the Kuomintang (KMT) government of the Republic of China launched a program in 1946 to use Hokkien as a bridge to learn Chinese.

However, after Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang lost to Mao Zedong's Communist Party in the struggle for control of China, Chiang planned to transform Taiwan into a base for retaking the mainland. Under the United States' containment strategy against the Soviet Union, the KMT regime accepted American aid. To prevent local Taiwanese intellectuals from participating in or opposing the authoritarian government and to deepen the divide between residents from other Chinese provinces and native Taiwanese, the KMT-led Republic of China government initiated a language suppression campaign. Speaking native languages (mainly Hokkien) instead of Mandarin Chinese was penalized in schools, often with fines. Over several decades, this policy significantly eroded the use of native languages among the post-war baby boom generation.

2. 台語與閩南語

Taiyu (Taiwanese Hokkien) vs. Hokkien

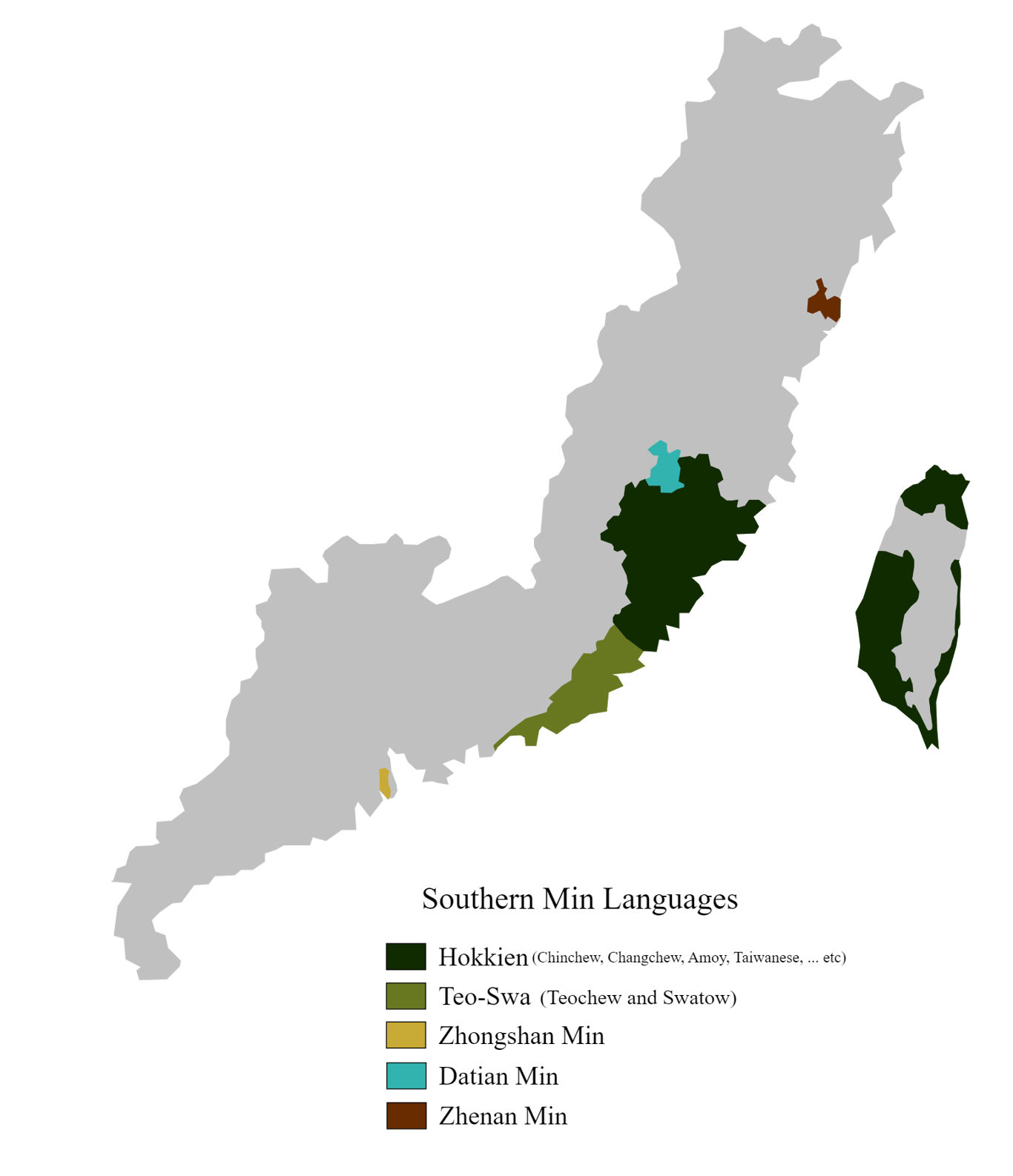

目前比較主流的學術研究,認為閩南語是中國福建一帶的漢語的方言,在語言學上屬於漢語支,由於福建省一帶的丘陵地眾多、造成了居民交流的物理隔閡,光是在閩南語內部就有很多地區腔調,並且除了閩南語外,還有閩北語、閩東語等差異略大的方言。

隨著大航海時代以後,遭遇小冰河飢荒時期的中國居民,受到歐洲國家船隻貿易與傳教的影響,明朝的中國沿海人民受到歐洲人聘請為廉價勞力到東南亞種植稻米、番薯、甘蔗,使得如今的東南亞(新加坡、越南、馬來西亞、台灣)有相當部分的閩南語使用人口。台灣最早的一批移民使用閩南語的人群,就是受到荷蘭東印度公司而來到台灣定居。

後續台灣正式成為中國清朝的領地,並後來因為戰爭割讓給日本,又遇到中華民國統治、受到美國援助,如今的台灣地區閩南語已經與其他地方的閩南語有小部分的用詞不同。在語言學研究圈中,認為台語(Taiwanese)是閩南語(Hokkien);然而台灣有一部分的人認為差異已有不同,是一個演化於閩南語的新的語言。台灣一部分人支持台語並非閩南語的原因,更多是屬於政治選擇,認為這樣子的語言名稱顯示了台灣這塊土地名稱、具有在地性,而非使用中國福建的古名"閩南",試圖想要脫離中國的華文文化國族論。

Current mainstream academic research suggests that Hokkien is a Chinese dialect originating from the Fujian region of China and linguistically classified under the Sinitic branch. Due to the hilly terrain in Fujian, physical barriers limited communication among residents, leading to significant regional variations within Hokkien itself. Besides Hokkien, other dialects like Northern Min and Eastern Min also exist in Fujian and exhibit notable differences.

Following the Age of Exploration, during the period of famine caused by the Little Ice Age, Chinese residents were influenced by European trade and missionary activities. Coastal communities in Ming dynasty China were recruited by Europeans as cheap labor to work in Southeast Asia, cultivating crops such as rice, sweet potatoes, and sugarcane. As a result, Southeast Asia, including Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Taiwan, now has a significant population of Hokkien speakers. The first group of Hokkien-speaking settlers in Taiwan arrived under the influence of the Dutch East India Company, establishing their presence on the island.

Later, Taiwan became an official territory of China's Qing dynasty, was ceded to Japan after a war, and subsequently came under the rule of the Republic of China, with additional influence from American aid. Over time, the Hokkien spoken in Taiwan has developed minor lexical differences compared to other Hokkien-speaking regions. In linguistic research, Taiyu (Taiwanese Hokkien) is considered a variety of Hokkien. However, some people in Taiwan argue that the differences are significant enough to classify it as a distinct language that has evolved from Hokkien.

Supporters of this view often base their argument on political considerations. They prefer the term "Taiwanese" to emphasize the connection to Taiwan's identity and local culture, rather than using the historical Chinese term "Hokkien," which references Southern Fujian. This reflects a desire to distinguish Taiwan from Chinese cultural nationalism and align more closely with the local identity of the island.

3. 台語的各種拼法、寫法

Various Systems for Writing and Romanizing Taiyu

目前台語的各種寫法如下:Current Writing Systems for Taiwanese Hokkien

台語正字:Taiwanese Southern Min Recommended Characters

閩南語原本就是中國唐朝中葉的中原居民,因為軍閥往南征而統治如今福建省一帶,由上古漢語(Archaic Chinese)與當地土著語言(原始閩語 Proto-Min)而混合成,再加上宋朝貴族因為與各族戰爭而退敗南下,再與中古漢語(Middle Chinese)混合,形成今日的台語。

因此在福建與台灣的知識份子,不但能講閩南語,而且也會寫漢字,而漢字面對正式文書(如宗教祭祀文、符咒與咒語、往明清朝政府溝通公文)都有另一套唸法。因此很多閩南語的字是能夠以漢字被書寫的。

然而也因為混有原始閩語,因此有些底層語言(特別是數字、日常用品與動植物的詞彙)並沒辦法有公認或對應的中文漢字可以書寫。所以2007年,台灣政府為了解決這個困難,所以利用中文字的造字法則,創造或者借用中文漢字,並且大量參考古中國字(現今幾乎沒有使用的字)。

Hokkien originated from the Central Plains residents of mid-Tang Dynasty China, who migrated southward during military campaigns and established dominance over what is now Fujian Province. It evolved through a mixture of Archaic Chinese and the indigenous Proto-Min languages. Later, during the Song Dynasty, aristocrats fleeing southward due to wars with various ethnic groups introduced elements of Middle Chinese, further shaping the language into what is now known as Hokkien, including its Taiwanese variant.

As a result, intellectuals in Fujian and Taiwan not only speak Hokkien but are also proficient in writing Chinese characters. For formal documentation—such as religious texts, rituals, talismans, spells, and official correspondence with the Ming and Qing governments—Hokkien employs an alternative set of pronunciations for Chinese characters. Thus, many Hokkien words can be written using existing Chinese characters.

However, due to the influence of Proto-Min, certain foundational elements of the language, particularly vocabulary related to numbers, daily items, and flora and fauna, lack universally accepted or corresponding Chinese characters. To address this challenge, the Taiwanese government in 2007 devised a solution by creating new characters or repurposing lesser-used historical ones, following the traditional principles of Chinese character construction. This effort relied heavily on references to ancient Chinese characters that are rarely used in modern writing.

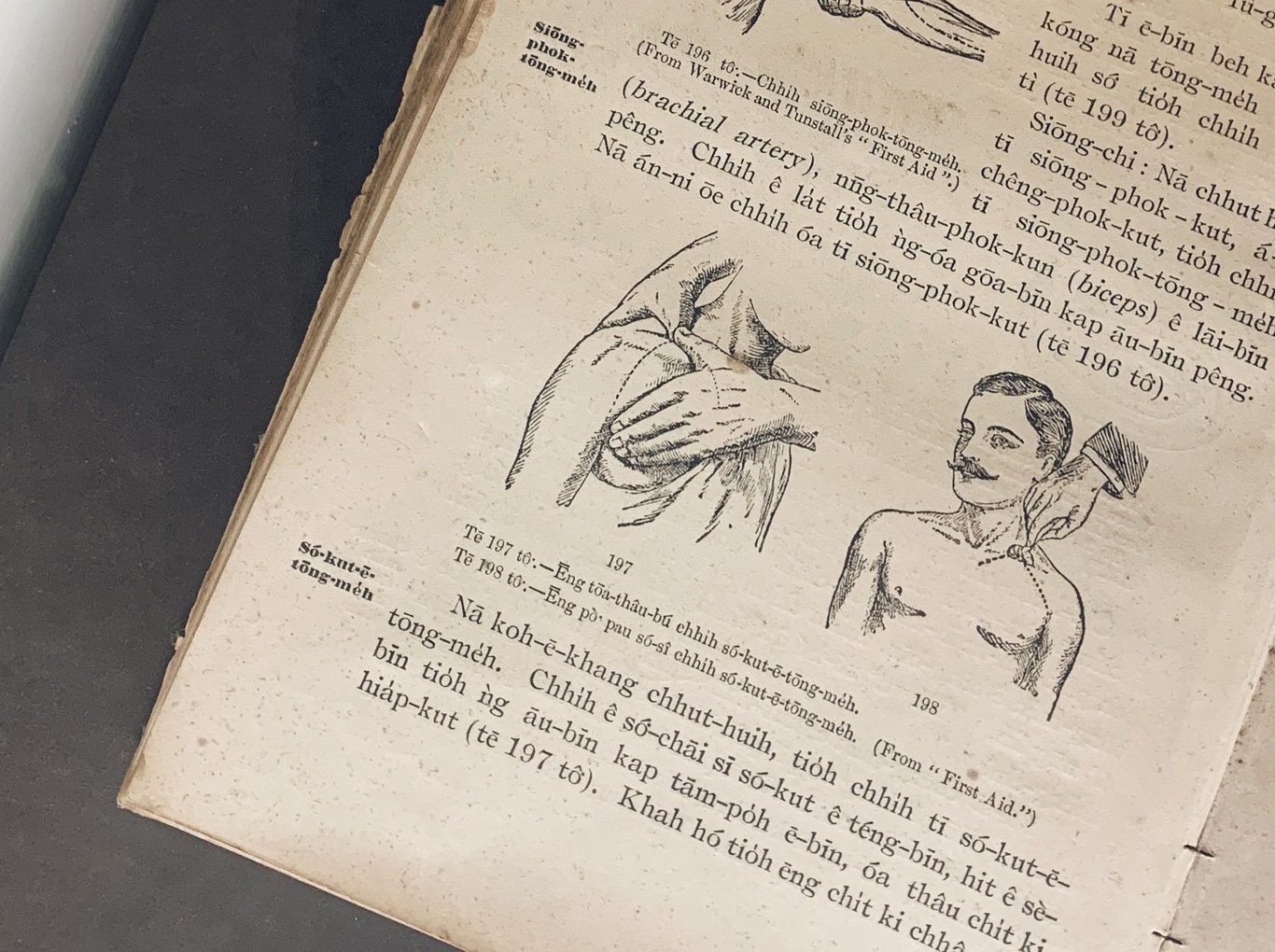

教會羅馬拼音/白話字:Hokkien church romanization script/Pe̍h-ōe-jī

教會羅馬字,是鴉片戰爭以後西方國家來華傳教士制訂和推行的各種羅馬字母(拉丁字母)拼音方案,教會羅馬字最早產生於英國殖民海峽地馬六甲,於1832年由傳教士麥都思(Walter Henry Medhurst,1796-1857)所制訂之閩南語(漳州地方口音)羅馬字拼音。旨在為傳教士和當地皈依者提供書寫和教授語言的語音框架。

Church Romanization refers to various phonetic transcription systems using Latin alphabets, devised and promoted by Western missionaries in China after the Opium Wars. These systems were primarily intended to help missionaries and local converts write and learn regional Chinese languages and dialects.

The earliest Church Romanization system for Hokkien was created in 1832 by British missionary Walter Henry Medhurst (1796–1857) in Malacca, then a British colony in the Straits Settlements. Medhurst’s system was based on the Zhangzhou (漳州) dialect of Hokkien and served as a phonetic framework for missionaries and local Christians to write and teach the language.

後期研發出來,白話字 Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ),它從英國長老教會傳教士甘為霖(William Campbell,1841-1921)的著作演變而來,但當時的台灣人民使用的依然還是閩南語,使用上與福建一帶的差異幾乎不存在。白話字後來成為1920年日本調查台灣人民識字人口1/3的台語使用語言。

Later, a more refined system known as Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) was developed. This romanization evolved from the work of William Campbell (1841–1921), a missionary of the British Presbyterian Church. POJ aimed to further standardize Hokkien romanization and was primarily used in Taiwan and Fujian.

At the time of its adoption in Taiwan, the local population predominantly spoke Hokkien, and linguistic differences between Taiwan and Fujian were minimal. In 1920, under Japanese colonial rule, a literacy survey revealed that one-third of Taiwan's population who were literate could read and write using POJ.

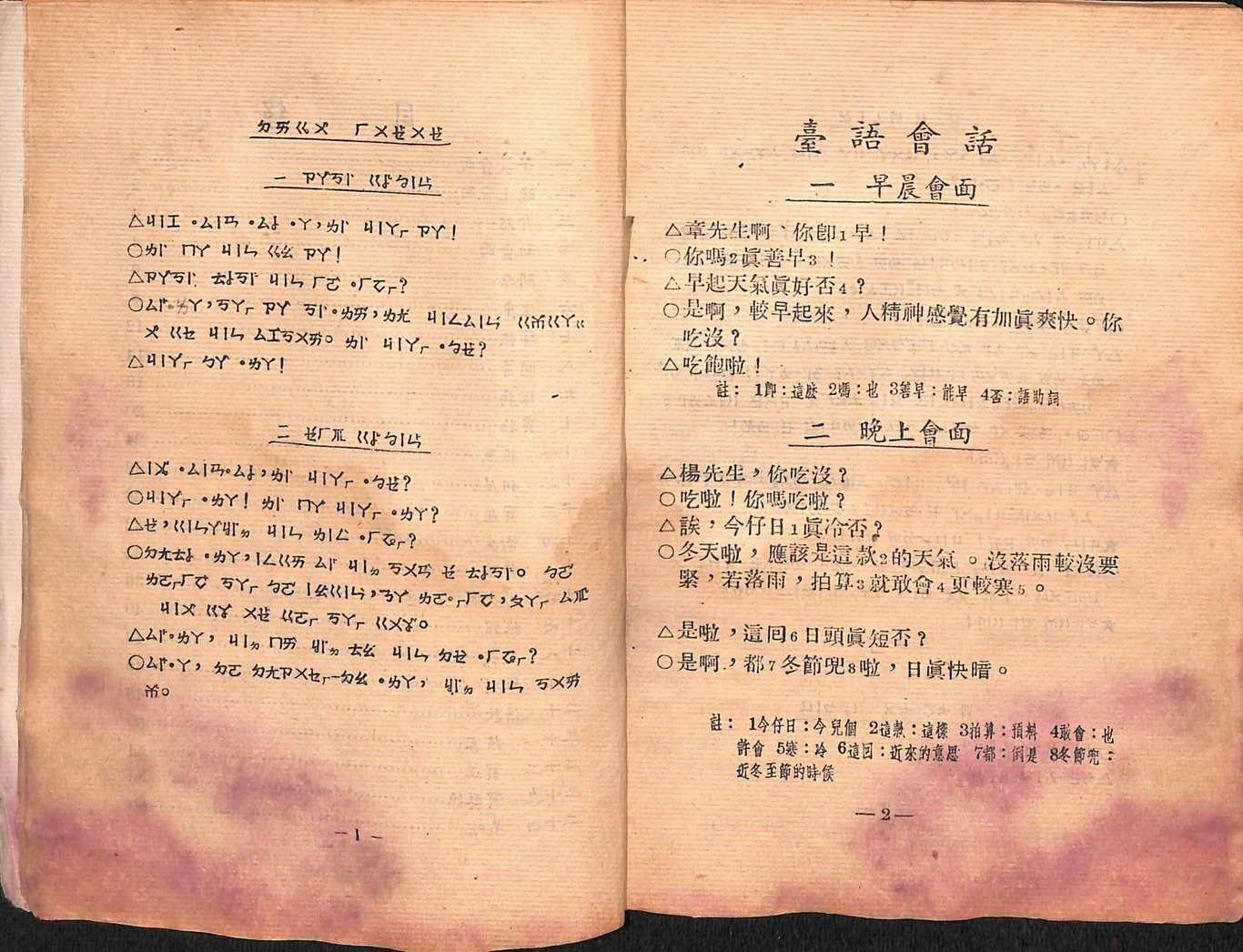

方音拼音方案:Taiwanese Phonetic Symbols

如前面所言,日本統治台灣時,為了推廣官方語言(日文),所以使用片假名來拼台語,除了教育目的也是為了統治而用的風俗調查學術目地。

During Japan's colonial rule of Taiwan, the Japanese government promoted the use of the Japanese language (Nihongo) as the official language. To facilitate this, they employed katakana to transcribe Taiwanese Hokkien. This was done not only for educational purposes but also for governance and academic research, such as ethnographic studies of local customs and languages.

當時中國因為多次與歐洲國家戰爭失敗,部分清朝的官員提出要進行教育改革、國民教育的理念,問題是中國各地的方言實在太多了,因此中國試圖想要透過詳細的語言學來拼寫各種方言的發音。此時中國學者章太炎(Zhang Binglin,1869-1936)因為用拳頭抵抗清朝政府而被通緝,躲到台灣來,學習到日本用片假名拼音台語的靈感,研發注音符號(Bopomofo)的雛形,使用一些中文字的簡寫來做為音標。

At the same time, China faced repeated defeats in wars with European powers, prompting some Qing officials to propose education reforms and the concept of national education. However, China's vast array of regional dialects presented a significant challenge. To address this, Chinese scholars began developing systems to phonetically transcribe the pronunciation of various dialects.

Zhang Taiyan (1869–1936), a Chinese scholar and revolutionary, became a key figure in this linguistic evolution. While on the run from the Qing government for his revolutionary activities, he sought refuge in Taiwan. There, he encountered the Japanese practice of using katakana to transcribe Hokkien, which inspired him to create an early version of what would later become the Bopomofo (Zhuyin) system. Zhang's system used simplified Chinese characters as phonetic symbols, laying the foundation for modern phonetic notation in China.

原本的中國語是參考北京話後,又再試圖揉合四川話、粵語、客家語、閩南語的半人工語言,希望全中國都有一個共同可以方便溝通的官方語言,一開始並沒有想要打壓其他方言的意思。然而部分教育學者因為使用習慣而大力反對後,只好回歸北京話為藍本的簡化語言,也就是現今的中國漢語。而那些原本可以拼客家語、閩南語音標,就成為了方音拼音方案。

Initially, China's national language project aimed to create a simplified, standardized language by blending elements of Beijing Mandarin, Sichuanese, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hokkien. This "semi-artificial language" was intended to serve as a common language for all Chinese people without suppressing regional dialects. However, opposition from some educators, who preferred the linguistic habits of Beijing Mandarin, ultimately led to the adoption of a simplified version of Beijing Mandarin as the foundation for Modern Standard Chinese (Putonghua).

The phonetic symbols originally designed for transcribing Hakka, Hokkien, and other dialects were repurposed into the Dialect Phonetic System (方音拼音方案) in later years. This system served as a tool for preserving and documenting the phonetic details of regional languages, although it never became widely used in practice. Meanwhile, Bopomofo remained a key phonetic tool, primarily for teaching Mandarin in Taiwan.