The Voices from Inside China: The Censored and Ignored Messages of COVID-19

Preamble

When an unknown disease (later named COVID-19) surfaced in late December 2019 in Wuhan, the Chinese authorities began increasing their internet censorship, according to research done by The Citizen Lab. When the epidemic had spreading globally by February 2020, the Chinese authorities claimed success in their containment of the outbreak, yet continuing to ignore thousands of messages for help from their own people. An engineer recognized this negligence and decided to build a database — Wuhan Crisis (武漢人間) — in order to save and archive these call-for-help messages.

An article from The Reporter (報導者) (original article) used these two important sources to highlight how the Chinese government conducted a campaign of Online Censorship and Public Opinion War in the face of the COVID-19 epidemic. This article highlights some of those struggling voices from China; voices that have been silenced, but needs to be heard.

This English translation is authorized by The Reporter (報導者) and has the licenses of CC BY.

Translator | COVID-19 Asia Observer

New Disaster under China’s Internet Censorship

Censoring hundreds of keywords and claiming themselves as the “global anti-epidemic role model”, how does Communist Party of China (CPC) fight the war against the public opinion of COVID-19 (Wuhan Pneumonia)?

Publisher | Reporter 報導者

Author | Jason Liu 劉致昕

Graphic | Gina Lin 林珍娜, Dada Wu 吳政達

The COVID-19 (Wuhan pneumonia*) epidemic has broken out globally. For the Chinese government, the most urgent battle they must fight is not only against the epidemic, but also that of the public opinion and consensus. In addition to the inaccurate and falsifying the reporting of those fallen ill and have died from COVID-19, large amounts of social media accounts, posts and groups sharing information to the disastrous conditions within China have also been made to disappear.

* Wuhan Pneumonia is the common name of COVID-19 used in Taiwan.

The Reporter interviewed The Citizen Lab from Canada and the Information Manager from Wuhan Crisis from China, and have obtained 561 censored words and more than 1300 call-for-help messages from YY and Weixin, two large social media platforms in China. With seeing these messages, we can better understand how the Chinese government strives to build a strong reputation in their fight against COVID-19 through censorship and propaganda. It must also be noted that countless number of these front line messages from both the people of Wuhan, as well as global public health experts researching and analyzing the epidemic situation, have all but disappeared within China due to the Communist Party of China (CPC) public opinion regulations.

On February 10th, a news article from the Chinese’s official media China Central Television (CCTV) caught the attention of the software engineer Xiaowu (pseudonym). In the article, it stated that up to February 9th, Wuhan officials had checked 3371 suburban regions in total, which account for 99% of people in the region.

In this broadcast, Ma Guoqiang, the Secretary of the Wuhan Municipal Party Committee (Editor’s note: he has since been fired from the office as of February 13th) discusses the progress of the epidemic in Wuhan. He states that as of February 8th, 1,499 patients whom had been diagnosed as severely ill, but have not yet to be admitted to hospital, have now admitted. CCTV also used “#Wuhan number investigation reached 99%” hashtag on Chinese social media, which went on to become a popular tag.

The disappearance of call-for-help messages from Wuhan pneumonia patients

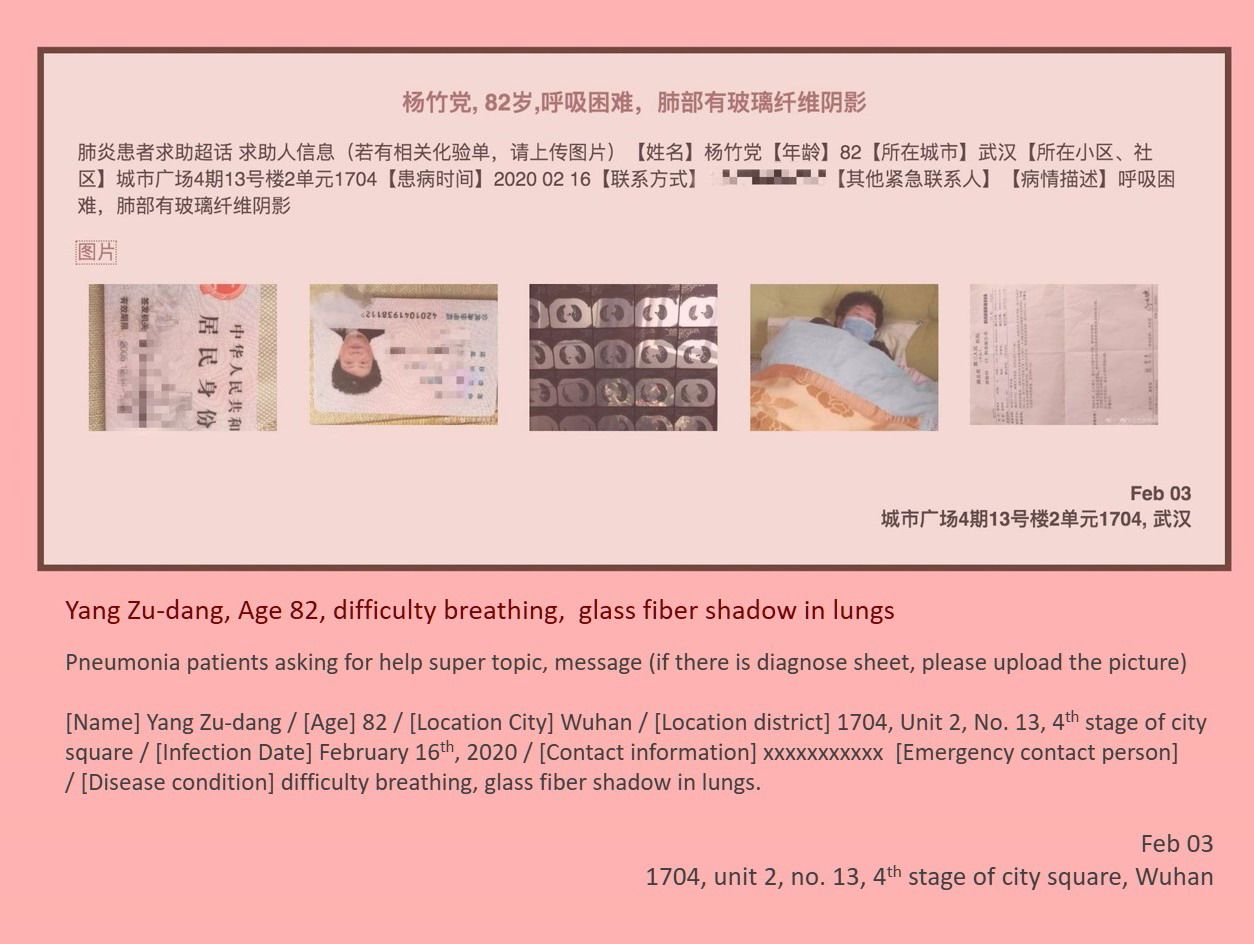

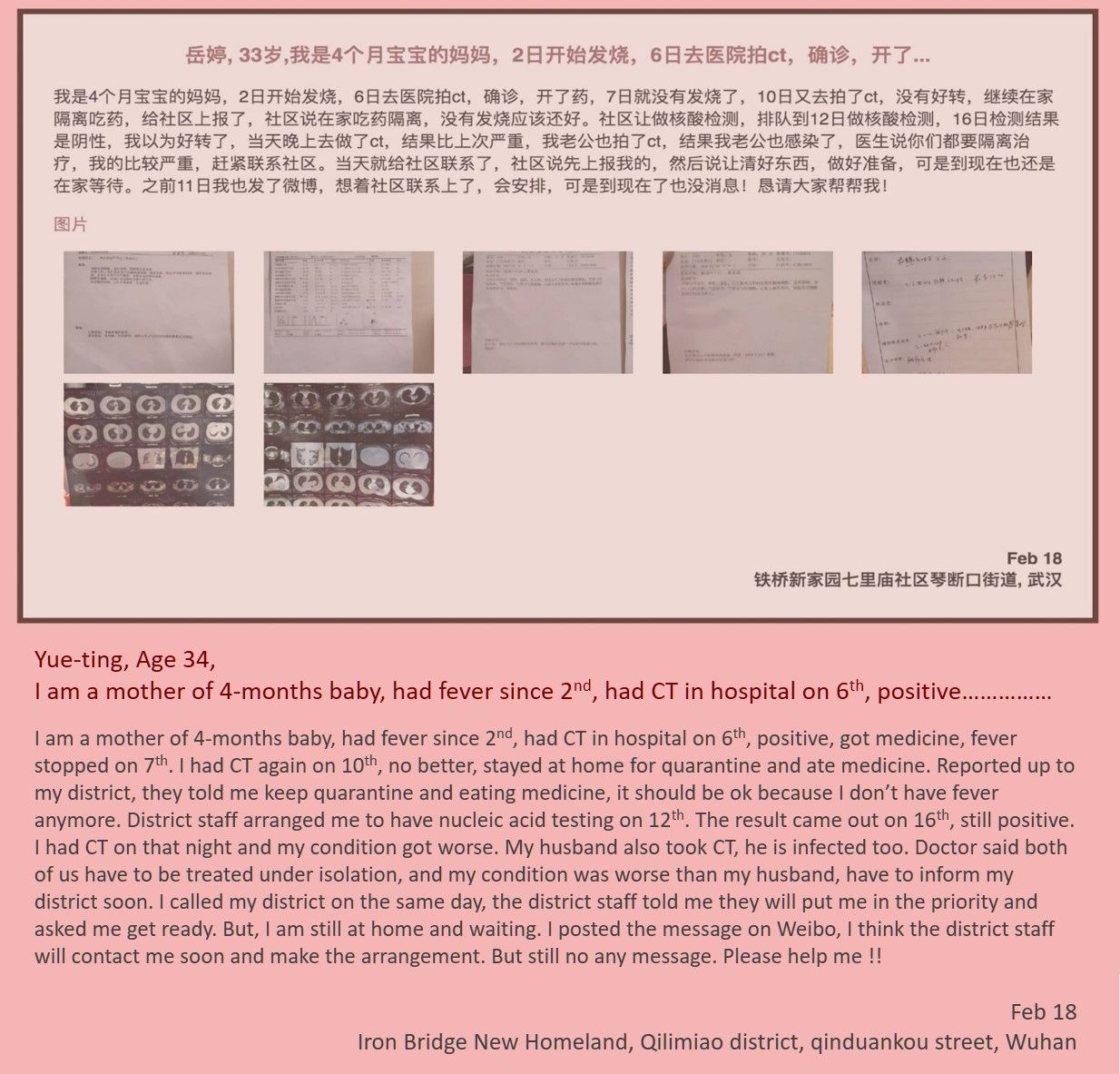

Xiaowu returned his gaze back to the world, away from the CCTV. As of January, there have been thousands of these “call-for-help” messages from Wuhan. Seemingly from hell and circulating on Weibo, it conveyed a sense of what was happening on the ground:

52-year-old Nie Lihua whom has had problems breathing for four days, needs oxygen. Unattended individual, and has yet to have nucleic acid test done.

32-year-old Qin Xiaoyue has been running a fever and is unable to get help as there has been no taxi’s or public transportation running since the city was shut down. She has received nothing after calling numerous times for help. She questioned, how do you get checked into the hospital?

52-year-old Zendi and 62-year-old Pu Honglian, the latter diagnosed with severe heart disease, have both had a running fever for eight days, yet no hospital would admit them.

90-years-old Huang Renqiang was seriously ill and could not get up at home. He did not have the chance to receive a proper diagnosis from the hospital.

A family member of 57-years-ld Wang Ping, died of COVID-19 and had contracted it himself. Since then, his direct family members have also been infected and his high fever has yet to abate. The community and quarantine hotels are pushing away responsibilities and unwilling to help. He has not had food for three days. He has problems breathing.

These were all public call-for-help messages posted by patients’ families and Xiaowu on Weibo. According to Weibo’s statement on February 5th, a total of 195,000 call-for-help posts were issued by all sectors of society in China, 473 of which were from hospitals, and all of which could only be shown publicly through their platform.

3000 articles were deleted. He overreacted himself and built an archive.

“It’s horrible. It’s too miserable, and it’s not matching with the news.” When Xiaowu accepted the interview from The Reporter, he said these call-for-help posts include information such as name, phone number, address, and even medical records. “These are the most authentic stories, and the voices of the people need to be remembered.” Xiaowu claimed that he had little to do at home, so instead had put in about twenty hours into creating the website “Wuhan Crisis” and began to record on it more than 1300 messages, beginning on February 3rd.

After he set up the website, Xiaowu was informed by fellow netizens that these distress messages have disappeared from Weibo. Since February 3rd, when the Weibo officials discovered the existing tag of “pneumonia patients asking for help super topic”*, the number of call-for-help messages dropped from more than 3000 daily to only 142. In this regard, the platform claimed that more than 80% of the call-for-help messages were invalid and so have been deleted.

* 超级话题 (Super Topic) is the specific tag Weibo used to link related posts.

“I personally hope that more people can find the stories of these individuals. They should never have encountered this catastrophe; and none of us is innocent”. Xiao Wu implied. He admitted that this is not the first time he has worked on a project that is socially meaningful. He refused to disclose more personal information on the grounds of safety. He does what he can to help as he stays at home due to the epidemic in China. His intention was not complicated and has no agenda. He had nothing to do at home, so he setup this website.

During this epidemic, he saw countless people rendered hopeless and aimless, as even the exposure of their last distress messages got reduced by the platform, through either Weibo’s limiting of internet traffic flow or by directly blocking accounts. Xiaowu felt that he had to do something. He spent days revising and improving the site after it was setup, so that through his work, he may find some peace in this chaotic situation.

“I hope the website will allow more people to pay attention and feel for every sick fellow citizen. Similar to us in body, through their first person narrative, we empathize their difficulties, pain, despair, separation and the death that they come to face.

Like trying to keep a verdant forest from a fire, Xiaowu ’s website inevitably cannot withstand the might of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in their fight against the public opinion war. Though the website has been viewed by more than 100,000 people and its contents have since been backed up by other supportive netizens, he was confronted by Xi Jinping’s war order.

“We must strengthen the guidance of public opinion, public communications, and interpretations of relevant policy measures.” On January 25th, the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee held a meeting on the epidemic. Xi Jinping instructed clearly to launch three major official battlefields: The Epidemic, Public Opinions and Psychology. On the day of the meeting, the WeChat Security Center announced, “notice regarding managing rumours related to COVID-19”, which within states that offenders could be imprisoned for up to seven years. As of now, the ringing of “Accounts Blocked” on Weixin has not stopped. Without reasons, countless accounts have since been locked from use. It became so frequent that “account blocked”’ even became a super topic on Weibo at one point. To circumvent government censorship in their criticisms, users have devised new ways to communicate such as through a morse code method, the use of “cui” 翠 (a combination of characters of “習 Xi” and “卒 soldier”) or the “collapsed emperor” to refer to Xi Jinping.

Analysis of 500 sets of keywords: epidemic blockade started as early as Li Wenliang whistled

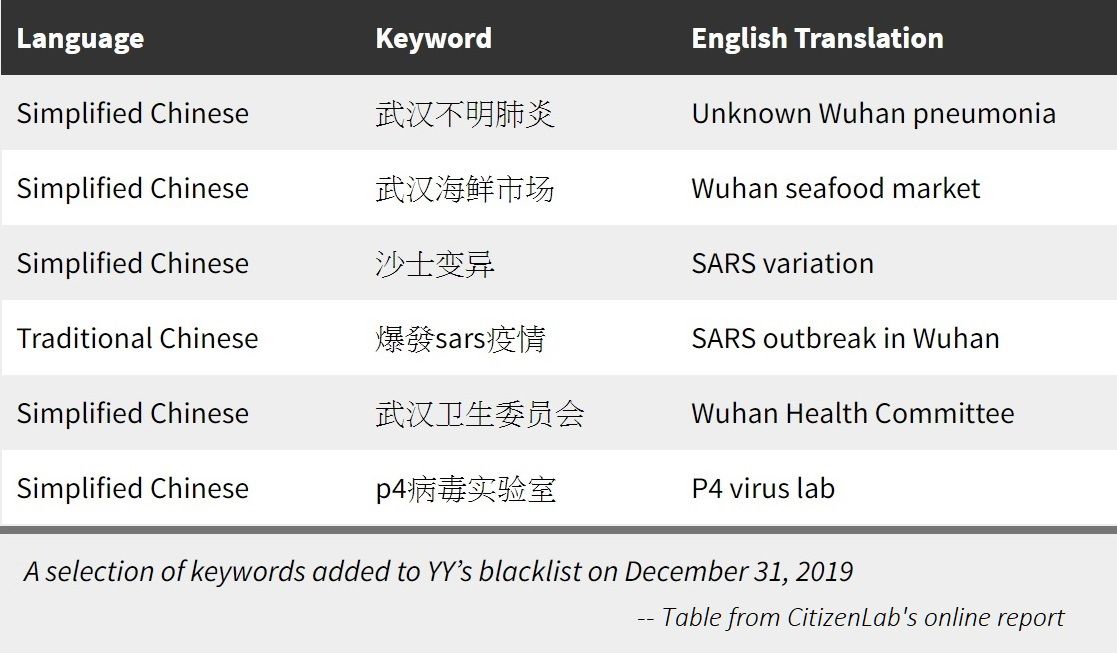

From University of Toronto’s The Citizen Lab’s report, The Reporter discovered that censorship had began as early as the end of 2019, soon after the physician Li Wenliang(李文亮) raised the Wuhan pneumonia warning in his group chat.

“According to the study, various social media platforms have started censoring relevant keywords before the CPC officially announced the situation of the epidemic (Editor’s note: January 20, doctor Zhong Nanshan was interviewed by CCTV) and the possibility of person-to-person transmission. It could possibly mean that these platforms received the government’s censorship requests earlier in the spread of the epidemic”. The Citizen Lab’s report stated, on December 31st, the day after Li Wenliang issued a warning message in the group chat, 45 keywords were added in the Chinese live-streaming platform, YY’s, censored list, most of which relate to Wuhan’s local government organizations, fresh markets, unknown viruses, and SARS symptoms. As long as the users’ messages include words such as P4 virus laboratory, seafood market, etc., messages cannot be sent.

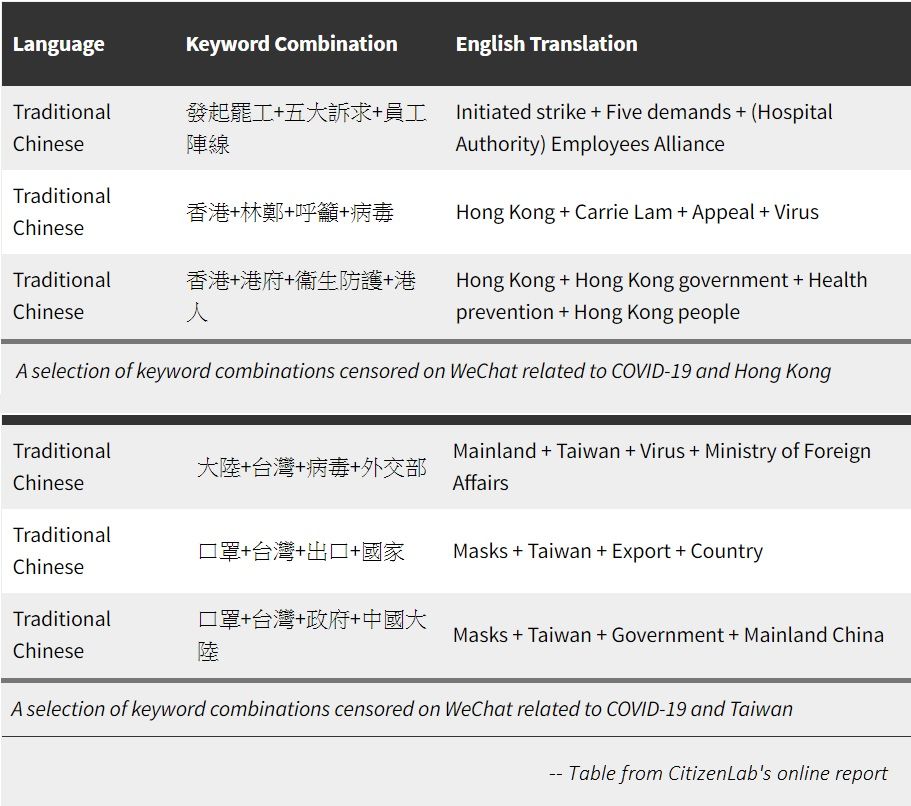

On the WeChat platform, which is used by nearly 1 billion people, The Citizen Lab discovered that during the most severe epidemic period in China between January and February, there were at least 516 new keyword combinations on the “review list”. Users who are registered with Chinese’ telecommunication companies cannot send out messages containing any of these 516 word combinations.

Of the 516 word combinations, nearly 200 relate to the central leadership — including Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang — and people’s criticisms of their inabilities, such as General Secretary Xi Jinping + formalism, Xi Jinping + accountability, Xi Jinping + slogan; discussions regarding whether the leaders personally visited Wuhan and the Huoshenshan Hospital, and words such as “cliff-like drop” are censored. The second is about governments’ roles and policies, criticisms of local governments, dissatisfaction with the Red Cross, “eaten by dogs”, and even the “virus of officialdom,” a homonym of the Chinese phrase for COVID-19, are all added to the censored list.

It is also worth noting that Taiwan’s mask export ban policy, Hong Kong’s Carrie Lam’s unwillingness to close borders between Hong Kong and Mainland China, and Hong Kong’s medical staff’s strike have also become censored words. Taiwan and Hong Kong’s “public opinion battle” during this epidemic are also controlled. In addition to Li Wenliang, words that are borrowed from Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement, such as “liberate” Wuhan, the “five demands” of the epidemic and other words about the civic movement were all blacklisted.

Concerns of losing control, even wordings from the government, media and objective facts are banned on internet platforms.

During the interview, Lotus Ruan from The Citizen Lab, noted that the massive censorship during the epidemic has shown to be quite similar to that of during the Lianghui (annual plenary session of the national or local People’s Congress and the national or local committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) where certain sensitive moments such as June 4th, are under scrutiny by online censorship. However the key difference is that the Wuhan pneumonia epidemic is a public health crisis that affects the entire world; yet under CPC examination, even the name, the incident and the descriptions of this crisis is blocked — this has severely affected the judgement and the preparation towards the pandemic when wide reaching platforms like Weixin, which is one of the primary social media platforms in China and globally, to receive and disseminate messages. She stated, for example that some of the censored keyword combinations include city lockdown, quarantine, court announcements, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), COVID-19, Western Medical Law and other fairly neutral words.

“Popular and intellectual information cannot be circulated, which can be very problematic, no matter what it is, [to handle] public affairs, health incidents.” Ruan stated.

Although there is no way to obtain internal documents, the The Citizen Lab, which has long observed Chinese censorship, points out that, “We know that the public and private sectors are managing the incident together, but from our observation, even the already published media reports (policy, incident name) are under investigation. It may be that platform operators are afraid that they can’t control the level of spread of the discussions and speech, so they expanded their scopes of censorship”.

The testing method of The Citizen Lab on WeChat mainly selects topic keywords from Chinese media. Since WeChat accounts distinguish between Chinese users and international users, the laboratory passes a potential censored word/phrase to a Chinese user through an international account. The result is, the censored words will only appear on the screen of the international client but not the Chinese user on the other end. This is the testing method.

Ruan explained that texts that can be published in the Chinese media have already passed the first level of government review; however various combinations of these words may be censored online. This means that the social media platforms believe that these words and phrases, when appear on social platforms, may not be officially recognised or they might become too popular to control. “To prevent the loss of control, simply censor.” Ruan described.

Through past documentations and research, The Citizen Lab pointed out that during major events or sensitive moments, Chinese social platform companies tend to receive government pressure. Though we can’t know clearly the specific demands that Chinese government put on private sectors, the results of this report indicate that the platform may have received official guidelines to start the censorship, as early as the end of December 2019, the day after Li Wenliang whistled.

Chinese government’s two-hands strategies: powerful censorship and magnified propaganda

The “Public Opinion War” in CPC’s perspective includes both censorship and propaganda. “Censorship and propaganda are two sides of one coin. In China, it causes a long-term contradiction. Censorship is conducted by private sectors.” Ruan pointed out that the extensive censorship toward COVID-19 may come from the combination of the government and the private sectors. In the system, the Chinese government is in charge of publishing the regulation and guidelines, which then private sectors have to invest resources, technologies, and manpower to conduct the censorship. If there are any violations, the platforms themselves will be held accountable.

However, there is a time difference between private sectors’ actions and the government’s orders. When private sectors cannot keep up with the government’s censorship management speed or when they realize that they cannot receive clear instructions, the private sectors will expand their censorship scope to protect themselves from being blamed.

Due to the pressures from government authority, private sectors have widely expanded their censorship controls. On February 5th, “Cyberspace Administration of China” published an announcement, which states that if any platform violates the policy, there will be immediate repercussions, including the mobile application taken off the shelf, related personnel questioned by the authority accordingly to the law, and the company/platform will be required to reform and restructure. The announcement directly called out SinaWeibo*, Tencent*, ByteDance (the parent company of TikTok*), and other platforms as such for strict inspection. According to The Citizen Lab’s research report, it was around the beginning of February where they started to notice massive amounts of censored keywords and when Weibo started to restrain the call-for-help posts.

After a wave of powerful review, the Chinese authority initiated a propaganda machine. Since late February, the Chinese government reshaped themselves within the narrative from the country who exported the virus, to the country who has successfully defeated the virus. China announced the plan to publish the book, “China combating COVID-19 in 2020 (大国战疫) *“ in five languages where they can share their experiences. According to Xihua News 新華社 (a government media), with 100,000 words, the entire book “objectively describes how China strongly and effectively prevents and controls this epidemic devil with scientific attitude and a common language.”, “It shows that China has been actively collaborating with the international society to collectively protect and maintain global and regional public health.”

When Elizabeth C. Economy, the C. V. Starr senior fellow and director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relation, was interviewed by The New York Times, she indicated that Xi Jinping is facing international scrutiny and criticism as the virus spreads globally. By thrusting out a public opinion war, “Xi reshapes the image of China, an attempt to shrug off any responsibilities, and avoid the international community’s requests to disclose the truth.

* SinaWeibo:It owns “WeiBo 微博”. It is a Chinese microblogging platform with over 445 million users.

* Tencent: the biggest Chinese internet company. It owns “WeChat 微信”, the major direct messaging system which has 1 billion users.

* Tik Tok: It is a video-sharing social networking service which is used worldwide.

* The book received many negative comments in China after release. It went off the shelf on March 1st.

Blocking messages sacrificed public health

The desperate attempt Xi Jinping took to control the perception of the situation, has turned into an over-extensive information censorship, which in turn has been made with the sacrifice of control over the pandemic and public health. Ruan pointed out that the way CPC “managed” information this time, censoring even objective facts, imposes concerning effects on the efficacy of battling the epidemic. Ruan reminded us that information controls — fact-checking, anti-conspiracy, or providing accurate information — are not unacceptable when facing a public crisis, and instead needs to be conducted with transparency and accountability. However, the censorship in China is not only vague but truths are also blocked. Ruan said: “It has caused a completely opposite effect when the CPC limited discussion and information exchange among the public, which not only limited people’s awareness of the epidemic but also their responses to COVID-19.”

Peter W. Singer, a specialist on 21st century warfare who wrote the book, Military Culture and Cyber security, had released an article that discusses how China initiated the public opinion in this pandemic by utilising the common techniques used by totalitarians: censorship, focus diversion, and lies.

Singer indicated: “China’s use of these three techniques clearly shows how the launch of cyber warfare, though protecting their power, can reversely harm public health.” He referred to what The Citizen Lab’s report has proved, how China chose to handle censorship first rather than the public health crisis on December 31st, 2019, the day after Doctor Li Wenliang blew the whistle. “This reveals what the totalitarian government really cares about.” Singer said.

China’s public opinion war jeopardizes the global public health warning system.

It is imperative that we recognize that it is not only Chinese people’s public health is being gambled and fought for under this public opinion war, but also that of the entire world’s when facing an pandemic. On December 31st, 2019, besides Dr. Li Wenliang’s warning, several global infection prevention systems such as HealthMap, ProMED, BlueDot also publicly released warnings regarding a SARS-like virus appearing in Wuhan. These systems use artificial intelligence to predict global outbreaks have successfully predicted the occurrence of Ebola and avian flu before Wuhan Pneumonia. After the occurrence of SARS, data scientists and public health experts tried to strengthen the global warning system through open data of healthcare, insurance, consumption, aviation, local news and social media. However, CPC’s attempts to delete, manage, and cover up “non-positive” internet content, planted mines that reduce the efficacy of these global early warning system.

Professor Ming-Hsiang Tsou, the director of Human Dynamics in the Mobile Age (HDMA) in University of California, San Diego, had conducted and published research about using Twitter data to track flu. He explained in The Reporter‘s interview that contents on social media platforms are helpful for people to prepare, react, recover and respond (in the long term) in disaster prevention. Decision-makers can use these data sets to better understand the effect of the policies, people’s reactions and further master the situation of an epidemic.

As an example, Professor Tsou proposed that the geographical locations of these thousands of COVID-19 call-for-help posts from Wuhan could allow the government to determine where new detection points may need to be added. The design of China’s real-name system enables the government to easily grasp the virus distribution of the population. The amount of call-for-help posts allow the government to evaluate the effectiveness of their measures, such as if the establishment of mobile cabin hospitals really reduce the call-for-help needs? Most importantly, these posts were so detailed and realistic that they can be useful when building a future epidemic prediction model.

When new technology bumps into old problems

Professor Tsou recalled at the time of the SARS epidemic, the international community missed the first opportunity to respond due to the delayed report from CPC. After SARS, experts searched for multiple methods, hoping to build a global automatic data analysis system to help predict the spread of unknown diseases. However, the effectiveness of the system depends on the transparency of data and sharing of information.

Seventeen years later, people did have new techniques, but progress failed due to old problems.

“(At the time) many posts from China immediately disappeared (censored). If such information is key in the early stages of the epidemic, the earlier we know, the less serious the spread. Like in Iran, a similar situation happened (censorship).” Professor Tsou believes that it is through transparency and openness that we can crowdsource knowledge to speed up in finding the solution to the epidemic.

Besides censorship, methods to control information also include active propaganda. Professor Tsou, living in the United States, pointed out that not only in China, American officials, when encountered COVID-19, also tried to reduce panic buying by stating “face masks cannot really prevent the virus.” He reminded us that decision-makers, when facing public crisis, have to find the balance between disclosing information and avoiding causing public panic, and it is often a challenge. In any case, the premise is that people’s privacy must be protected. For example, when revealing confirmed cases, it is ok to disclose their path records but not their addresses and names.

The Communist Party of China (CPC) chose to enhance centralized censorship.

The management of the epidemic situation not only requires sharing essential information openly and transparently within a country, but also globally. Professor Tsou explained: “If a certain region or country blocks information, we cannot know the current status, the starting point and the source of the epidemic, nor can we further find out the efficiency of the spread and the development of possible future prediction models. We would not be able to analyze the differences between various regions or discover conditions that may have affected the spread. If information is shared, people can gather and work together. Decisions made like this will exceed oligarchy or elitism, which may truly benefit the majority.

On the day of the interview, China’s most stringent network control regulation, “Provisions on Environment and Management of Network Information Content” (網絡信息內容生態治理規定), was officially activated. Furthermore, the “Alipay Health Code” (健康碼)* was put into practice where the Chinese authorities linked public health information to the police system, attempting to use new technologies to strictly control civilians’ freedom of speech and freedom of movement.

The Chinese’s style of battling COVID-19 seems to be determined to go against openness and transparency. Whether they can control the epidemic or prevent the next one from happening, we will have to wait for time to prove itself; but what is certain is that the world and the Chinese people’s expectations for a more transparent public health information system in China, have fallen short once again after the lessons from SARS.

* Alipay Health Code is a mobile system that uses software to dictate quarantines — green enables its holder to move about unrestricted; yellow requires the holder to stay at home for seven days and red means a two-week quarantine. The app appears to send personal data to police. (source New York Times)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!