哈维尔:人权高于国家主权——在加拿大国会的演说

野兽按:虽然天涯博客算是国内尺度最松的博客网站了,但是还是有不少文章发布后被隐藏。自2006年2月22日受李国盛邀请,要天涯开办【陈寿文专栏】,至今已经十四年了。不过自从2013年有了微信公号【心灵自由】之后,就很少使用这个博客,只是偶尔想起会去那里发一篇微信公号发布不了的文章。刚才看了一下数据。

- 访问:36511810 次

- 日志: 1400篇

- 评论: 5163 个

- 留言: 76 个

- 建站时间: 2006-2-22

后台总共有74篇文章被隐藏。今天开始,把这74篇翻出来。站友们,我又要开始刷屏了。

这篇被屏蔽应该不是正文的问题,而是我在评论上的回复文章。Roger N. Walsh是我非常欣赏的一个超个人心理学家,期望这两年能有一个美国之行,去拜访他以及斯坦·格罗夫和杰克·康菲尔德。

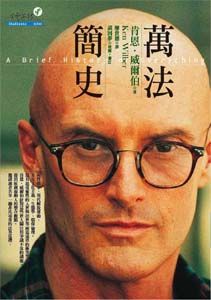

9.Roger N. Walsh

作者:陈寿文 提交日期:2008-12-13 1:07:00 | 分类:新知 | 访问量:978

Roger N. Walsh (MD, Ph.D.) is a professor of Psychiatry, Philosophy and Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine, in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, within UCI's College of Medicine. Walsh is respected for his views on psychoactive drugs and altered states of consciousness in relation with the religious/spiritual experience, and has been quoted in the media regarding psychology[1], spirituality,[2] and the medical effects of meditation.[3]

According to the University of California, Dr. Walsh is involved in six ongoing research areas: 1) comparison of different schools of psychology and psychotherapy, 2) studies of Asian psychologies and philosophies, 3) the effects of meditation, 4) transpersonal psychology, 5) the psychology of religion, and 6) the psychology of human survival (exploring the psychological causes and conseuqences of the current global crises).[4]

• The World of Shamanism: New Views of an Ancient Tradition (Llewellyn, 2007) ISBN 0-7387-0575-6

• A Sociable God: Toward a New Understanding of Religion --with Ken Wilber-- (Shambhala, 2005)

• Essential Spirituality: The 7 Central Practices to Awaken Heart and Mind (Wiley, 2000) ISBN 0-471-39216-2

• Paths Beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision --ed., with Frances Vaughan-- (J.P. Tarcher, 1993) ISBN 0-874-77678-3

• ^ "New evidence points to growth of the brain even late in life", New York Times, Jul. 30, 1985.

"Greenhouse Effect: The Human Response", Washington Post, Apr. 17, 1990.

"Survival could depend on your attitude", CNN, Jun. 1, 2005.

• ^ "Psychology of east gaining attention in western world", New York Times, Oct. 9, 1984.

"Mystic journeys breathing life into visions beyond the rational", San Jose Mercury News, Jun. 10, 1995.

"Web site gives scientists outlet for explaining the unexplainable", Sacramento Bee, Sep. 4, 2001.

"West meets East: UCI puts Eastern techniques under the microscope of Western scientific method", Orange County Register, Mar. 14, 2004.

• ^ "Meditation as Medicine", Orange County Register, Dec. 28, 2003.

"Doctors say meditation helps patients improve health", Kansas City Star, Feb. 1, 2004.

• ^ UCI Faculty Profiles: Roger N. Walsh

• The World of Shamanism at Llewellyn Publications

• Staying Alive: The psychology of Human Survival. Transcript of an interview with Walsh on the television series Thinking Allowed, Conversations On the Leading Edge of Knowledge and Discovery.

• UCI Faculty Profile for Roger Walsh

Roger N. Walsh

Positions: Professor, Psychiatry & Human Behavior

School of Medicine

Philosophy and Anthropology

School of Humanities

Degrees: PH.D., University of Queensland, Australia

M.D., University of Queensland, Australia

Research

Interests: Asian psychologies, Asian philosophies, Asian religions, Buddhism, ecology, meditation,exceptional psychological wellbeing, postconventional development, transpersonal psychology

Research

Abstract: Dr. Walsh is involved in six research areas: 1) comparison of different schools of psychology and psychotherapy, especially existential, humanistic and cognitive perspectives, 2) studies of Asian psychologies and philosophies, 3) the effects of meditation, 4) transpersonal psychology, which explores exceptional psychological wellbeing, 5) the psychology of religion and 6) the psychology of human survival: an examination of the psychological causes and conseuqences of the current global crises.

Publications: Walsh R and Vaughan F (eds). Paths Beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, 1993.

Walsh R. The Transpersonal Movement: A history and state of the art. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1993, 25:123-140.

Walsh R. The ecological imperative. Re Vision, 1993, 16:50-52.

Walsh R. Two Asian psychologies and their implications for Western psychotherapists, American Journal of Psychotherapy, 1988, XLIII:543-560.

Address University of California

B140D Medical Sciences 1

Mail Code: 1675

Irvine, CA 92697

Phone: (949) 824-6604

Fax: (949) 824-7012

Email: rwalsh@uci.edu

Updated 04/22/2002

The Intuition Network, A Thinking Allowed Television Underwriter, presents the following transcript from the series Thinking Allowed, Conversations On the Leading Edge of Knowledge and Discovery, with Dr. Jeffrey Mishlove.

STAYING ALIVE:THE PSYCHOLOGY OF HUMAN SURVIVAL with ROGER WALSH, M.D.

JEFFREY MISHLOVE, Ph.D.: Hello and welcome. Today we're going to be talking about an extremely profound topic, the psychology of human survival -- and in fact, explicitly, the psychology of the survival of the human race. My guest, Dr. Roger Walsh, is a psychiatrist and a professor at the University of California, and also the author of a very interesting book called Staying Alive: The Psychology of Human Survival. Roger, welcome.

ROGER WALSH, M.D.: Thank you very much.

MISHLOVE: It's a pleasure to have you here. In your book you look at the big problems facing humanity -- global nuclear war, pollution, overpopulation -- and you come to a very interesting conclusion. You suggest that all of these problems are man-made; they reflect our minds, our psyches, and that certainly one angle for dealing with these problems has to be psychological. What got you involved in these issues? So many people really don't want to face the big problems.

WALSH: That's true, and it's really quite understandable. If you look at the magnitude and urgency and complexity of the problems we're up against, it's really no surprise that most of us feel pretty uncomfortable when we look at them. And yet when we're brought face to face with them, it's really hard to keep the veils of denial and repression up. For me the veils were torn away when I went to Asia. I spent a couple of months there studying and doing research. Although I thought I knew about the state of the world, it was really quite a shock to me to find out firsthand just how most of the people in the world live, and to live with these people, and from day to day see the conditions which they were surviving under.

MISHLOVE: I had the experience myself this year. I've been to the Orient several times, and I can remember being in Shanghai, a city of some fourteen million people -- crowded. It's like the Bay-to-Breakers Race all the time.

WALSH: Yes, it's hard to imagine.

MISHLOVE: The per-capita income is something like less than the equivalent of two hundred and fifty dollars a year.

For an intelligent, well-bred individual, it's horrifying in some ways.

WALSH: That's true, and in fact one billion people live on an annual income of less that two hundred dollars a year on the planet at the moment.

MISHLOVE: It's hard for us to appreciate, when we consider less than five thousand a year is poverty. I heard somebody say recently, "If you're not making at least a hundred thousand dollars a year, you're living in poverty."

WALSH: Well, that's a very generous definition of poverty, and not something which most of the world's population would understand.

MISHLOVE: Not at all. So you were moved by your personal experience of seeing this?

WALSH: I was very moved by that. It really made me rethink; it made me realize I'd really been asleep about the state of the world. Then when I came back to the States I started reading, and it didn't take more than a few days of reading about the global situation for me to appreciate that I just had not understood what we were up against, and to let some of those facts in was mind boggling. Then I saw the film that the Physicians for Social Responsibility, the Nobel-Prize-winning group, put out, called The Last Epidemic, on the medical consequences of nuclear war, and that was another eye opener. Again I realized I'd just been ignoring the greatest issues of our time. And then it was very hard to stay asleep.

MISHLOVE: You know, there are some optimists, perhaps people in the current administration, who would argue that what's really going on in the world now is a redistribution of wealth because of the forces of the free market, which is why we're buying Japanese and Korean automobiles -- so that those workers there, because of their poverty, can compete more effectively in the workplace and the labor market.

WALSH: Well, to some slight extent that's true. There is some redistribution going on in that way. But unfortunately the facts are very clear, and that is that the gap between the wealthy nations, the haves of the world, and the have-nots, is growing, so that the poor are getting poorer and the rich are getting richer to some extent. In part that reflects many of the other problems we're facing, such as population explosion -- most of the population explosion is occurring in Third World countries, which can ill afford it. Starvation of course is occurring in these countries; we lose twenty million people a year of starvation, fifty thousand a day. That's extraordinary. And so this idea that things are kind of correcting themselves is not true. It can be corrected; I think that we have to appreciate that we do have the power, we have the technology, the resources, the information, to correct the problem, to handle the global threats. But it's a question of whether we are willing to really make that our priority.

MISHLOVE: I think the most striking statistic -- and in your book you cite many statistics -- the one that really got to me the most was the notion that we spend worldwide, I think you said some six hundred and sixty billion dollars on armaments and the arms race and the military. And maybe one percent of that would be sufficient to end world starvation.

WALSH: You know, those figures are extraordinary. And the tragedy is, Jeff, that those figures are a couple of years out of date now. This year for the first time the world will spend over a trillion dollars on weapons -- one trillion dollars. That's three billion dollars a day. You know, if you spent a million dollars a day since the birth of Christ, you wouldn't have gotten through more than about two-thirds of a trillion dollars. That's how much it is. If you compare that with the amount needed to eradicate world starvation, which has been estimated by the Presidential Commission on World Hunger at about six billion dollars a year, that's a lot of money, but it's less than one percent, as you said, of the world's arms expenditures. So one year of the world's arms expenditure would eradicate starvation for a hundred and fifty years.

MISHLOVE: Somehow it makes me angry at us when I hear you say that. It's like there's something in our minds, collectively, where we have agreed that, as I think you put it in the book, we can't afford to feed the starving, and we can't afford not to build up these arms. Honestly, Roger, it makes me angry to think that this is what we collectively believe.

WALSH: Well, that's probably a very healthy response, because the state of the world is almost one of insanity, and we have to really appreciate that before we can start working effectively. Because, as you pointed out in the introduction, for the first time in human history each and every one of the threats we're facing to human survival -- whether it be nuclear weapons or overpopulation or starvation or degradation of our environment -- each and every one of these is human-caused, which means it stems from our behavior, from our ways of thinking and acting and perceiving, and is ultimately traceable to the psychological forces within us and between us. What that means is that what we've called our global problems are actually symptoms; they're symptoms of the distorted ways we look and perceive and think and believe and act. And unless we appreciate that we're only going to treat symptoms, and the way most of us have treated or tried to treat global situations is with the military, economically, or politically, and it hasn't gotten us too far. Of course those are absolutely essential. But unless we recognize that the state of the world is a reflection of the state of our minds, and try to heal our perception -- to see more clearly, to reduce our fear and paranoia, and to correct our beliefs to get correct information -- we're not going to get it handled.

MISHLOVE: You know, I had a discussion with a spiritual teacher, Idries Shah, the Sufi master, about this issue over ten years ago. I said to him, "You know, at this point we have to wake up. We have to become enlightened. We have to change. It's a matter of survival." And he said, "Yes, that's absolutely true, but if you put it to people that way it won't work. That's not the reason that people are going to wake up."

WALSH: What was his suggestion as to why people would?

MISHLOVE: Well, listen to Sufi stories? I don't know quite what he had in mind.

WALSH: I'm a little more pragmatic.

MISHLOVE: You're putting it more directly, aren't you?

WALSH: Well, I think it's very possible that the situation might evoke from us more mature responses. There are two things that could happen out of this, because these threats have really strong effects on us. We can deny and repress all we want, but there's no way we can escape completely the effects of the fact that our lives hang by a thread and we have no guarantee that any of us, or our culture, or our friends, or our loved ones, are going to be here tomorrow. That has major effect. What that means is we could go two ways. On the one hand, the very threats we've created could exacerbate the fear and paranoia and defensiveness that got us here in the first place; or on the other hand, if a sufficient number of us are really willing to face these honestly and act appropriately, then we might be able to reverse the situation and even perhaps learn and grow in the process. Because it's going to take more than we've had before. It's going to take new levels of individual and collective responsibility and maturity and growth and collective action. So it's just possible that the very threats we've created might act as catalysts to pull us out of the situation. That's a hope, I think.

MISHLOVE: That's the optimistic view of things.

WALSH: That's the optimistic view.

MISHLOVE: As in a Shakespearean tragedy, it will bring out the noblest.

WALSH: Of course the reality is, we don't know. We don't know that we're going to survive. We have no guarantees whatsoever, but it doesn't seem to make sense to do anything except work like hell to ensure that we do.

MISHLOVE: What you have done -- and I certainly want to go into this in some detail -- is you've analyzed the situation psychologically, using the various schools of psychology and what they can offer, from behaviorism all the way to transpersonal and the spiritual aspects of psychology. Yet there are those who suggest that the problem isn't really psychological, quite. They suggest that what we really have to come to terms with is the problem of evil itself. How do you address that?

WALSH: Well, I think we need to take a real close look at what we mean by evil. You can look at unskillful behavior, behavior which causes incredible suffering to people, either in terms of evil and malevolence, or you can look at it terms of it being an expression of people's mistaken beliefs and fears and paranoia. And it's very interesting -- what comes up for you when you hear the word evil?

MISHLOVE: Well, one thinks of the religious mythologies and Satan, or the notion of absolute evil, embattled, locked like day and night.

WALSH: That's it. And when there's evil, then the automatic response is to attack and defend and feel very righteous about it. So what I'd suggest is that seeing people acting in terms of evil is very dangerous, because one of the sad facts of human nature is that we tend to become what we believe our enemies are, and to justify our actions in terms of theirs. So if we see them as evil, then we're likely to respond in the same way ourselves.

MISHLOVE: Well, the classical example of this would be the Inquisition, where the Church tortured and killed ten million people in the name of Jesus, because they were evil.

WALSH: For their own good. For the good of their souls.

MISHLOVE: And yet this notion of evil, which you seem to be challenging in a very intelligent fashion, is embodied in most of the major religious traditions today.

WALSH: It is, at some levels, and yet some of the more sophisticated religious teachings tend to see unskillful behavior more in terms of an expression of people's fear and defensiveness, and try to heal that rather than trying to attack and destroy the person who has it.

MISHLOVE: So one of the things that you're saying is that our tendency to label the problems that we're having as resulting from evil in the world, that in itself is an illustration of part of the problem, from a psychological perspective.

WALSH: Yes, and a very tricky one too, because we can feel so righteous when we're battling evil. We're on the side of light. It's always interesting, if you look over history, that everyone always thinks they're on the side of the light and angels, and no one's ever fighting for the devil.

MISHLOVE: Then of course there's the classic statement of Reagan. The focus of evil in the modern world becomes the Soviet Union, and it has this almost religious aura, like we're getting ready for a holy war here.

WALSH: Of course that's a real danger. Whenever throughout history people have seen the "enemy" as entirely evil, then there's been a tendency to engage in battle, to attack them.

MISHLOVE: And another level here, mythologically speaking, may be in the Bible itself, the myth of Armageddon -- we're moving towards this gigantic nuclear war, and it's God's will.

WALSH: Yes. That's a very tricky belief. I think you're pointing to something very important here. You're pointing to the beliefs that may be operating in the culture which may pull us towards mass suicide, particularly when those beliefs aren't recognized as only myths, or only beliefs. When we either don't recognize these myths are operating in us, or we just assume automatically that they're the truth, then they have power over us. So one of the crucial issues, I think, what's really facing us here, is firstly to recognize the power of myths and beliefs, and then to recognize the beliefs that we hold, and to recognize that they're just beliefs -- that they are statements about reality which we tend to take for reality.

MISHLOVE: You cite the statistics of young children today, schoolchildren -- what? eighty, ninety percent of whom anticipate a nuclear war now in their lifetime.

WALSH: There are a large percentage of kids who fear that.

MISHLOVE: I may have overstated it, but it's high.

WALSH: Yes, it's high, it's very high. And that's a very scary fact, because if these kids don't have any reason to think they're going to live out their life, then it leads to a sense of hopelessness, depression, despair, and quite possibly an exacerbation of feelings of aggression towards society and so forth. It's a very dangerous situation we're facing.

MISHLOVE: You see it reflected in the young countercultures now -- the punk movement, the new wave movement. They've changed from the days of the hippies, say.

WALSH: Well, the younger generation always keeps reacting against the older, so I'm not sure we can blame it entirely on the nuclear situation. But there's no question that the global threats have embedded themselves deep in the minds of all people, young and old, American and Soviet, and are having their impact. The question is whether we can face these facts, open ourselves to them, look at them honestly, and out of that honest looking allow ourselves to be touched by them. And to the extent we're touched by the enormity of preventable suffering in the world, and the possibility of this useless mass killing, to that extent we're likely to react with compassion and concern and contribution. The ancient wisdom was, "The truth will set you free," and that's not only good theology, it's very profound psychology as well. So one of the first things we have to do is just keep looking truthfully at the situation we've created.

MISHLOVE: And to start out with, I guess what you're saying is to recognize the severity of the problem.

WALSH: Recognize the severity of the problem, and also recognize the extent to which it's a creation of our own minds and our own beliefs and our own misperceptions, and then start working on those.

MISHLOVE: I suppose for the sake of clarification we might start with -- I think the big ones must be population, pollution, nuclear war, starvation.

WALSH: Indeed, those are the big ones we're facing.

MISHLOVE: The big four. Have I missed any?

WALSH: Well, that covers a lot. There are others, of course -- climate changes and carbon dioxide increase. But we don't have to list ad nauseam. The message is very simple. We've got lots of problems. And they're solvable, if enough of us are willing to take responsibility and start acting. One of the things that's really crucial here, I think, is for us to appreciate that these problems are solvable. Not only are they solvable, but each of us can make a useful contribution here. One of the problems that so many of us have is the feeling of hopelessness and helplessness: what the heck can I do, I don't have the facts, or I don't know enough, or I'm too this or I'm too that. There's a wonderful quote by Henry Ford, which I love. Henry Ford said, "Those who believe they can do something and those who believe they can't are both right." I think that's a pretty potent statement. It really is a message of hope and empowerment for all of us, to appreciate that if we believe that we can make a contribution, we can.

MISHLOVE: And that's exactly what you're doing.

WALSH: Well, that's exactly what we're trying to do now, and what many people watching will be doing as well.

MISHLOVE: Let's now begin to outline some of the major areas where you see a psychological dynamic that we can focus in on. For example, behaviorism is a school of psychology that seems to be saying quite a lot about these problems.

WALSH: Well, each school says quite a bit. Behaviorism, for example, emphasizes the role of rewards and reinforcers, and also the role of modeling -- that is, the people who are put up to us as role models. For example, if we want to look at the role of the media here, which is incredibly powerful, then who are the stars? What is presented to us on TV? We find that the heroes of Western television tend to be rewarded for being aggressive and highly consumptive, using a lot of raw materials and so forth -- exactly the things which are creating these problems.

MISHLOVE: You know, there's kind of a cycle there, because the major networks believe that they have to put this on in order to get market share; and so a lot of people must believe that that's what they want to see.

WALSH: Well, as long as those examples are provided to us of what's successful and what makes people happy, as long as the media keep fostering that illusion, then for sure that is what people will tend to watch. I think we really need a new generation of heroes. You know, John Wayne is not going to keep us on this planet.

MISHLOVE: But we do have Bill Cosby.

WALSH: We have Bill Cosby, right. There may be hope yet.

MISHLOVE: So what you're saying as regards behaviorism is that we need to provide positive models.

WALSH: Yes, we need positive models, particularly given the power of the media and the fact that an average kid spends more time in front of TV than in front of a teacher. So we really need this, and we need to be aware of what we're reinforcing people for. For example, we reinforce our politicians for supplying unlimited amounts of raw materials -- for example, gasoline -- right now, even though it may mean that our kids face a very drastic situation.

MISHLOVE: Nobody thinks in the long term. We think now about oil glut. Five years ago we were thinking otherwise.

And five years from now, who knows?

WALSH: Five years from now again, yes. We don't reward our politicians for that type of long-term thinking.

MISHLOVE: In fact just the opposite. The system seems to have short-term rewards built in. This is the teaching of the behaviorists -- that the closer the reinforcement or the reward follows the behavior, the more people recognize it. So built into the very nature of the human organism is shortsightedness.

WALSH: That's true, and so we need to do things to make us more aware of the long-term consequences. One example of that that's now institutionalized is the necessity of environmental impact reports, which make it clear to everyone what exactly the long-term impact of major institutional changes is going to be. That's one example of what can be done.

MISHLOVE: What in effect we're doing, as I see it, is we're kind of telescoping. We're taking a long-term impact, which might be a reinforcer of some kind, and we're saying okay, you've got to have this report ready next month. So we're making it into a short term, by requiring the environmental impact report be done.

WALSH: Well, we're making ourselves aware, right now.

MISHLOVE: Are you saying that awareness is enough, that if we're aware of the fact that we only look towards short-term reinforcements, that that will actually change?

WALSH: Well, awareness is healing, there's no question about that. I'm not sure it's enough by itself.

MISHLOVE: Behaviorists would probably not say so, I would take it.

WALSH: Right, exactly. Some other schools might. But I don't think anyone would argue with the idea that awareness is crucial to healing both the individual, the culture, and the planet.

MISHLOVE: And it may be our best point of leverage.

WALSH: It may indeed. One of the best things any of us can do, I think, is to educate ourselves, to educate other people, just to know the facts, because once we know the facts, that tends to evoke appropriate responses. So the first step is always education. H.G. Wells said it very well. He said, "Human history is becoming more and more a race between education and catastrophe." That's very true now, more true than when he said it.

MISHLOVE: If we were to look at education today in its optimal sense, what I think we'd be needing to do is to give people a whole perspective of what's really happening, in the largest possible sense.

WALSH: That's right. We really would need to be giving more courses about the global situation, the whole planet, the state of our world. There are very few courses like that in colleges or schools at the moment. But they're getting more, and that's very hopeful, that the education is beginning to shift. I see it in the University of California, where I work, and I feel encouraged by that.

MISHLOVE: As a psychiatrist, what about our understanding of the unconscious dynamics of the mind? Freud I think seemed rather hopeless about the human situation, because he saw all this muck -- aggression, libido, and so on -- going on in the unconscious. How do you deal with that?

WALSH: Well, Freud was a little bit of a pessimist about the human condition. I'm not sure I'd want to agree completely with that. I think the reality is that all of us have the potential for positive and negative, and we react according to circumstances -- environment, upbringing, etcetera -- so we're a lot more malleable, changeable, than perhaps Freud would have wanted to believe. So that gives me a little hope. But clearly unconscious factors play a large role. For example, the role of fear operates unconsciously, and we respond to our fears by what we call defense mechanisms, whereby, for example, we repress and deny our awareness of the situation, or we project onto other people those parts of ourselves and those motives we're unwilling to recognize and acknowledge in ourselves. So then, for example, we turn out to be lily white and they turn out to be evil and malevolent and bad and vicious and all the things that we're not.

MISHLOVE: How do we put a stop to that?

WALSH: Well, knowing about these processes is very helpful, first off. Once you know that all of us tend to project, all of us tend to repress and deny at bit, no one's perfect -- at least I haven't met any perfect human beings, and I've been looking for some time. So all of us do these, and once you know that, then it gets very hard to deny that these forces are operating between nations and between leaders as well as between you and me, for example.

MISHLOVE: In other words, when we label someone as enemy, we make them all bad, and we think of ourselves as all good. The truth of the matter, I suppose, is that our enemies aren't as bad as we think they are, and we're not as good as we think we are.

WALSH: Well, the truth often tends to be somewhere in the middle, yes. And the interesting thing, of course, is that we look out and we see our enemies -- for example, the Soviets -- as evil and bad and wicked, and they look at us and see us exactly the same way. So there's something very interesting going on there. There's this mirror image that we hold of each other.

MISHLOVE: What do we do about that?

WALSH: Well, again, I think you pointed to one of the things -- that's information, just letting in accurate information. You know, for a long time it wasn't even allowed to teach or talk about Communism openly in this country for a while. And of course the Soviets do a tremendous amount of censoring. So letting accurate information in is one thing. Getting people in contact is another, just allowing greater contract. One of the interesting developments is this movement of citizen summitry, with people going across to the Soviet Union, inviting the Soviets here, getting to know one another firsthand. That clearly breaks down some of the stereotypes.

MISHLOVE: What do the spiritual psychologies -- if you can tell us in about a minute -- have to say about these issues? Perhaps we could conclude on that note.

WALSH: Well, let's see. I think the spiritual psychologies, some of the Eastern psychologies, would point to the role, for example, of greed or addiction and hatred and anger, and of what they call delusion; that is, not seeing clearly -- the appreciation that our mistaken beliefs and defenses distort our perception of one another, and of other nations.

MISHLOVE: In other words, by not being in touch with our deepest, truest self, we're acting out of false values.

WALSH: That puts it very nicely. Yes, that's good, that's very good.

MISHLOVE: Well, Roger, the sense that I have from being with you is that just by being able to discuss these things, and maybe share them with other people as we're doing now, that that's a step in the right direction.

WALSH: I certainly hope so.

MISHLOVE: And that's something that everybody can do.

WALSH: Absolutely everyone, yes.

MISHLOVE: And perhaps it's something that will continue to grow and snowball.

WALSH: I hope so.

MISHLOVE: Roger, thank you very much for being with us.

WALSH: Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity.

END

评论人:陈寿文 | 评论日期:2008-12-23 0:25

哈维尔:人权高于国家主权——在加拿大国会的演说

独角兽资讯 发表于 2008-2-3 15:37:00

尊敬的总理、参议长、众议长、参议员、众议员,各位来宾:

能在这里演说,我的确感到非常荣幸。我愿借此机会就国家及其可能在未来的地位说一些看法。

所有迹象表明,作为每个民族共同体的发展顶峰与人类的最高价值----事实上这是可以为其杀人或值得为它而死的唯一价值----的民族国家,已经越过了其最高顶点而开始走下坡路。

若干代追求民主人士所从事的启蒙事业,两次世界大战的可怕经历,对於制订世界人权宣言以及人类文明的全面发展,作出了非常重要的贡献,似乎正逐渐使人类认识到,人比某一国家更为重要。

在当今世界,国家主权的偶像一定会逐渐消解。当今这个世界透过在商业、金融、财产,直到信息方面的数以百万计的整合性联系,将各国人民联为一体;这种联系还提供了各种普遍观念和文化模式。而且,在当今的世界,对一些人的危险会立即影响到其他所有人;由於许多原因,特别是由於科学技术的巨大进展,我们各自的命运已融合为一种单一的命运;无论我们喜欢与否,我们都要对发生的一切承担责任。

显然,在这样一个世界里,盲目热爱自己的国家,把爱国置於至高无上地位,仅仅因为它是自己国家而为它的任何行动寻找借口,仅仅是因为不是自己国家而反对其他国家的任何行动,这种爱国必然变成一种危险的时代颠倒,一种产生冲突的温床,最终会成为无数人类苦难的源泉。

我认为,在下一个世纪,大多数国家将开始从那种类似邪教团体的、诉诸情感的实体,转变为更为简单的、公民享有更多管理权力的单位。这种单位将拥有较小的权力,但它更富于理性,它仅仅是一个复杂的、多层次的、社会自我管理的全球组织的层次之一。这种转变,要求我们逐渐抛弃那种互不干预的观念,即那种认为其他国家发生的事,其他国家对人权尊重与否,与己无关的观念。

谁来承担现在由国家行使的多种功能呢?

首先来看国家在诉诸情感方面的功能。我认为,这些功能将被更平等地分配给组成人类同一性的多层次的领域,即人类活动於其中的多层次领域,也就是我们看作自己家园或自然界的各种领域,家庭、公司、村庄、城镇、地区、专业、教会、协会,以及我们所在的大陆和我们居住的行星----地球。所有这些组成我们的自我认同的多种环境。而且,迄今已膨胀过度的我们与自己国家间的连系如果受到削弱,这必定有利於其他领域。

至於国家的实际职责与法律制度,可以向上和向下转移。向下转移是指国家应该把其现行的许多职权,逐步转移给公民社会的各种组织和机构。向上转移是指国家把其许多职权,转移给各种地区性的、跨国的和全球性的团体和组织。这种职权转移现已开始进行。在某些地区,这种转移已走得相当远;在另一些地区则进展较小。

然而,由於许多原因,这种发展趋势必须沿著这条道路继续发展下去。如果界定现代民主国家的特徵,通常包括尊重人权和自由、公民平等、法治和公民社会,那麽作为人类未来目标的这种生存方式,或者人类为自己的生存而应该朝著它前进的生存方式,也许可以被界定为一种以世界性或全球性的尊重人权、世界性的公民平等、世界性的法治和全球性的公民社会为基础的生存方式。

民族国家建立过程中伴随的一个重要问题是国家的地理边界,即其疆界的确定。无数的因素,包括种族的、历史的、文化的因素,地理因素,权力利益,以及整个文明状态,都在其中起著重要作用。

建立地区性或跨国性的更大共同体,有时会遇到同样的问题。在某种程度上,这种问题可能从加入共同体的民族国家那里继承而来。我们应该用一切力量来保护这一自我界定的过程不会像民族国家的建立过程那麽痛苦。

例如,加拿大和捷克现在是同一防御性组织--北大西洋公约组织的成员。这是一个具有历史重要意义的发展过程,即北约扩展到中欧和东欧国家的结果。这一过程的重要性在於,它是为了打破铁幕、在真实上而不仅在口头上废除雅尔塔协议,所迈出的真正严肃的、历史上不可逆转的第一步。

众所周知,这一扩展过程远非容易,而且是在两极对立的世界结束十年後才成为现实。进展如此困难的原因之一,是由於俄罗斯联邦的反对。他们对此不理解而且十分担心:为何西方要向俄罗斯附近国家扩展,而不接纳俄罗斯?如果我在此刻撇开所有其他动机,俄罗斯的这种态度暴露了一个非常有趣的问题,即俄罗斯世界或东方世界对自己的地理疆界□不清楚。北约与俄罗斯结成夥伴的前提条件是:地球上存在著两个对等的强大实体,即欧洲-大西洋实体和广袤的欧洲-亚洲实体。这两个实体可以而且必须相互携手合作,这对全世界有利。但之所以能这样做是因为双方都意识到自己的身份,都知道自己的范围在何处。在这个问题上,俄罗斯在其历史发展过程中就遇到某些困难,并把这些困难带到现今世界,而在现今世界,地理边界不再涉及民族国家,而是涉及文化和文明的地区和区域。的确,俄罗斯有许多与欧洲-大西洋或西方相联系的东西,但如同拉丁美洲、非洲、远东、其他地区或大陆,俄罗斯也有许多与西方不同的东西。世界的各地区存在著差别,这一事实并不意味著有些地区比另一些地区更有价值。它们是互相平等的。它们仅仅在某些方面有所不同。但不相同□不意味著可耻。俄罗斯在一方面认为自己是一个实体,是一个应该受到特殊对待的全球强国;另一方面,它又因为自己被看成是一个独立实体,一个很难成为另一实体之组成部分的实体,而感到不舒服。

俄罗斯正在逐渐习惯北约的扩展,有一天它会完全习惯这种扩展。我们希望,这将不仅是恩格斯所谓的被认识到的必然性的一种表现,而且是新的更深刻的自我理解的一种表现。在这个多元文化、多极化的新环境里,正如其他国家必须学会重新界定自己,俄罗斯也必须这样作。这不仅意味著,它不能永远以自大狂或自恋来代替自然的自信心,而且意味著它必须认识到何处是自己的疆界。例如,拥有丰富自然资源的广袤无边的西伯利亚,属於俄罗斯;而小小的爱沙尼亚就不属於并永远不属於俄罗斯。而且,如果爱沙尼亚属於北约或欧盟所代表的世界,俄罗斯必须理解和尊重这一点,而不应把这看成是一种敌意的表现。

只要人类能经受人类为自己准备备的所有危险的考验,二十一世纪的世界将是一个以平等为基础的,人类在范围更大的、有时甚至覆盖整个大陆的跨国组织内更密切合作的世界。为了使这个世界变成现实,人类文明的各种实体、文化或领域必须清晰地认识到自己的身份,了解自己与别人的差异所在,认识到这种差异性不是一种障碍,而是对人类全球财富的一种贡献。当然,那些对自己的差异性抱优越感的人也必须认识到这一点。

联合国是所有国家和跨国实体能坐在一起平等讨论、并做出决定影响整个世界的最重要组织之一。联合国如果要成功地完成廿一世纪赋予它的任务,必须做重大改革。

联合国的最重要机构安理会,不能继续维持它刚开始成立时的状况。相反,它必须公正合理地反映今日的多极化世界。我们必须思考,某一个国家是否一定有权否决其他各国的共同决定。我们必须考虑,许多重要而强大的国家在安理会内没有代表权这个问题。我们必须探索轮流性的安理会非常任理事国等制度问题。我们还必须减少整个联合国庞大机构的官僚主义,提高其工作效率。我们必须讨论如何才能使联合国机构,特别是其全体大会的决策过程具有真正的弹性。

最重要的是,我们必须使地球上所有居民确实将联合国看成是自己的组织,而不只是一个由各国政府组成的俱乐部。最关键一点是,联合国应该是为地球上全体人类而不是为了个别国家谋利益。因而,联合国的财务程序,会员国申请程序和审批程序,也许应该加以改革。这并不是要剥夺国家的权力并以某种庞大的全球之国取而代之,而是不能让一切事务都一定要而且只能通过国家及其政府来处理。正是为了人类的利益,为了人权、自由以及一般意义上的生命的利益,应该存在多种渠道,使世界领袖的决策到达公民,并使公民达到世界领袖。多种渠道意味著更多的平衡和更广阔的相互监督。

显然,我不是在反对国家机构。一国的首脑在另一国的国会演讲时宣传国家应该废除,这是相当荒谬的。但我讲的是其他问题。我讲的是,事实上存在著一种高於国家的价值。这种价值就是人。众所周知,国家要为人民服务的而不是与此相反。公民服务於自己国家的唯一理由,是因为对於国家为所有公民提供良好服务而言,公民的服务非常必要。人权高於国家权利。人类自由是一种高於国家主权的价值。就国际法体系而言,保护单个人的国际法律优先於保护国家的国际法律。

在当今世界,如果我们各自的命运已融合成单一的一种命运,如果任何人都应对全人类的未来负责,那麽,任何人,任何国家,都不应拥有胡制人民履行自己职责的权利。各国的外交政策应该逐渐脱离那种常见的构成其核心的东西,即自己国家的利益,自己国家外交政策的利益,因为这类利益倾向於分裂而不是团结人类。确实,人人都有某种利益,这是完全自然的,没有理由认为我们应该抛弃自己的合法权利。但有一种东西高於我们的利益,这就是我们信奉的原则。这些原则能团结我们而不是分裂我们。而且,这些原则是衡量我们的利益是否具有合法性的标尺。许多国家的教义是,为了国家的利益而坚持某原则,这种说法站不住脚。原则必须为了其自身而被尊重或坚持。就原则而言,利益应该来源於原则。例如,如果我说,为了捷克的利益才需要有公平合理的世界和平,这是不对的。我应该说,必须有公平合理的世界和平,而捷克的利益必须服从於它。

北约正在进行一场反对米洛谢维奇的种族灭绝统治的战争。这既非一场可以轻易获胜的战争,也非一场人人拥护的战争。对於北约的战略战术,人们可能存在著不同观点。但任何具有正常判断力的人都不能否认一点:这可能是人类并非为了利益、而是为了坚持某种原则和价值所进行的第一场战争。如果可以这样评价战争的话,那麽这确实是一场合乎道德的战争,一场为了道德原因而打的战争。科索伏没有可以使某些人感兴趣的油田,任何北约成员国对科索伏没有任何领土要求,米洛谢维奇也没有威胁任何北约成员国或其他国家的领土主权。尽管如此,北约却在打仗,正在打一场代表人类利益、为了拯救他人命运的战争,因为正派的人不能对国家领导下的系统性地屠杀他人坐视不管。正直的人绝不能容忍这种事,而且,绝不能在能够救援的情况下而不施援手。

这场战争将人权置於优先於国家权利的地位。北约对南斯拉夫的攻击没有获得联合国的直接授权。但北约的行动并非出於肆无忌惮、侵略性或不尊重国际法。恰恰相反,北约的行动是出於对国际法的尊重,出於对其地位高於保护国家主权的国际法的尊重,出於对人权的尊重,因为人权是我们的良心及其他国际法律所明确阐明的。

我认为,这场战争为未来立下了一个重要的先例,它已明确宣告,不允许屠杀人民,不允许将人民驱离家园,不允许虐待人民,不允许剥夺人民的财产。它还表明,人权不可分割,对一些人不公正也就是对所有人的不公正。……

过去我曾经多次思索,为何人拥有的某种权利高於其他任何权利。我得到的结论是,人权、人的自由和人的尊严深深地置根於地球世界之外。它之所以得到这种地位是因为在某些环境下,人类自觉地而不是被迫地把它看成是一种重於自己生命的价值。因而,这些观念只有以无限空间和永恒时间为背景才有意义。我坚信,我们的所有行动,无论它们是否与我们的良心相和谐,其真实价值最终将在某个超出我们视线的地方接受检验。如果我们感觉不到这一点,或者下意识地怀疑这一点,我们将一事无成。

对於国家及其在未来可能扮演的角色,我的结论是:国家是人的产物,而人是上帝的产物。

(戴开元1999年6月译,发表在同月《世界周刊》及《北京之春》)