The quiet diplomats: how Germany kept up pressure on China to free Liu Xia

It had to travel half a world but in April last year a plea from Chinese poet Liu Xia reached the hands of German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Liu Xia, the wife of imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, was under de facto house arrest in Beijing and had written a note clearly expressing her desire to leave China and settle in Germany with her husband and brother.

The note was handed to Merkel by the chancellor’s long-time friend, singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann and included an appeal on Liu Xia’s behalf by the poet’s friend and Berlin-based exiled Chinese writer Liao Yiwu.

“I am all the time in contact with Merkel. She grew up in the beginning in dictatorship and nobody has to teach her what it means,” Biermann said.

That spring day was the end of a long-distance effort to directly petition one of the world’s most powerful politicians. It was also the start of an aggressive 15-month campaign of quiet German diplomacy that resulted in Liu Xia’s release and arrival in Europe on July 10.

Widespread awareness of her ordeal contributed to her release but it was the back-door diplomatic efforts that finally paid off, experts said.

THE DECISION TO LEAVE

Liu Xia’s decision to leave China was a long time coming.

After her husband was sentenced to 11 years behind bars in late 2009, Liu Xia was prepared to wait patiently in silence for his return home from a prison in Jinzhou in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, friends said.

She became a virtual prisoner herself after Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 for co-authoring Charter 08, a manifesto calling for sweeping democratic political reform in China.

Almost immediately, Liu Xia was completely isolated, cut off from the world outside her home except for weekly escorted trips to see parents and buy groceries.

She was also allowed to make monthly trips to Jinzhou for half-hour visits with her husband but prison management forbade her to speak of her own ordeal.

‘Chaos and disbelief’: Liu Xia’s last hours in China before her flight to freedom

The couple had been a priority for Western diplomats for years but the envoys’ hands were tied because both Liu Xia and Liu Xiaobo refused to leave China.

German diplomatic efforts at the time could only focus on improving Liu Xia’s conditions in China.

Liu Xia was never charged with any crime and the Chinese authorities insisted that she enjoyed freedom as a Chinese national according to law.

“It is a matter falls within China’s judicial sovereignty. She is a Chinese national [and] we of course handle the relevant issue in accordance with our laws and regulations,” foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang said in May.

But through repeated and failed attempts to visit her, the German embassy in Beijing showed the Chinese authorities that “the fiction created about Liu Xia being a free person was not convincing”, according to Katrin Kinzelbach, associate director of the Berlin-based Global Public Policy Institute.

“From the very beginning of her house arrest, German diplomats went to her door, tried to see her, delivered books and tried to support her. They persistently asked the Chinese authorities to end the illegal detention against Liu Xia, but all these efforts had little effect,” said Kinzelbach, who tracks diplomatic negotiations related to human rights.

Foreign diplomats blocked by security guards at home of Liu Xiaobo’s widow

Liu Xia’s hardships were compounded in 2013, when her younger brother Liu Hui was convicted of fraud and sentenced to 11 years in a case that critics say was to punish her for speaking to the media and seeing friends several months earlier.

The death of her father in September 2016 and her mother in April 2017 added to her mountain of grief to the point where Liu Xia could no longer cope, according to friends.

It was a turning point. Persuaded by her friends, Liu Xia finally told Liu Xiaobo about her struggles in March last year and he changed his mind about staying in China.

A PERSONAL PLEA

On April 9, 2017, Liu Xia wrote a note to the “relevant [Chinese] officials” overseeing her case for permission to go to Germany with Liu Xiaobo and Liu Hui for medical treatment, offering to live “a quiet life”. A copy of the note was given to Merkel and posted by Liao on social media.

“My friends have been in contact with the German government and they welcome our family. Whenever I have spoken to the German ambassador on the phone, he has always said the German government is willing to provide us with whatever we need and welcomes us to Germany,” Liu Xia wrote.

Kinzelbach said it was essential that Liu Xia stated her desire in unambiguous terms.

“It was very important that she communicated very clearly that she wants to leave China. That changed the entire picture,” she said.

Once a top-level political interest had been established, front-line diplomats would identify their Chinese counterparts to negotiate with, she added.

Merkel appeals to China for ‘humanity’ for ailing Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo

Behind-the-scenes talks were soon under way between Berlin and Beijing but the couple’s plight worsened when her husband was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. Soon, a second letter written by Liao urgently appealing for help with Liu Xiaobo’s critical condition was delivered to Merkel, calling on her to raise Liu’s plight with Chinese President Xi Jinping during the G20 summit in Hamburg that July.

Neither Germany nor China revealed what the two leaders discussed in Hamburg but Merkel’s spokesman said at the time that “the tragic case of Liu Xiaobo is a great concern for the chancellor and she would like a signal of humanity for Liu Xiaobo and his family”.

PUBLIC PRESSURE

While Berlin had embarked on a course of quiet diplomacy, a Berlin-based coalition of influential intellectuals was maintaining pressure in public. The group included Liao, Biermann, Independent Chinese PEN Centre president Tienchi Martin-Liao, Nobel literature laureate Herta Müller and publisher Peter Sillem.

The members lobbied, marshalled resources, mounted protests, made petitions, and promoted Liu Xia’s profile to raise public awareness and keep political attention focused on the couple.

Kristin Shi-Kupfer, director of research on public policy and society at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin, said efforts from civil society helped keep the case on top of the German government’s agenda and persistent high-level intervention expedited her case.

Multiple sources told the South China Morning Post that the US government also pressured China for Liu Xia’s release, with the White House, the US embassy and members of Congress working in step with German diplomats.

The US-German cooperation was most evident when medical specialists from the two countries were granted permission to assess and advise Liu Xiaobo in his intensive care unit ward at a tightly watched Shenyang hospital.

Writers urge China to release Liu Xia, widow of jailed Nobel Peace Prize winner

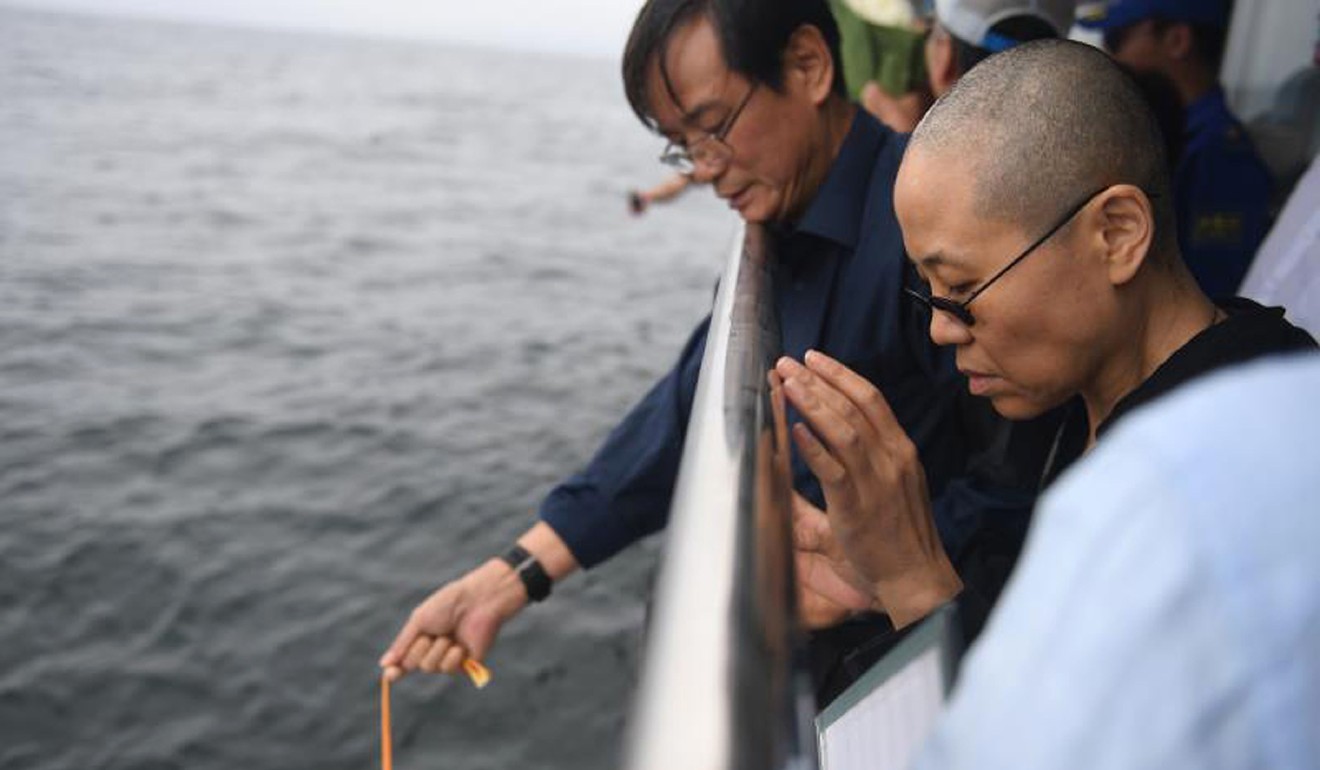

The doctors made a last-ditch appeal for Liu Xiaobo to be treated overseas but to no avail. He died in custody on July 13 at the age of 61, the first Nobel Peace Prize laureate to die in prison since pacifist Carl von Ossietzky died in Nazi Germany in 1938.

According to the transcript of a phone call between Liu Xia and Liao, Liu Xia said it was her husband’s dying wish for her to leave China.

“He [Liu Xiaobo] told me I had to get out of the country … In the end he stopped speaking – he just kicked his leg to show what he meant. His legs kept moving, almost like he was walking, non-stop, for over an hour, both legs walking non-stop … without stopping,” the transcript quoted Liu Xia as saying.

A PASSPORT OUT

With the laureate’s death, the international focus shifted to his widow and ensuring she could leave China.

“After the passing of Liu Xiaobo, the negotiations just focused on pushing to issue her a passport, remove non-official guards from her house and get her on the plane,” Kinzelbach said.

Unlike other political prisoners, Liu Xia was never charged with a crime so technically there was one less barrier to her departure.

Diplomats on the ground kept up their attempts to visit Liu Xia to remind the Chinese authorities that the problem would not go away by itself, Kinzelbach said.

German and US envoys also kept up pressure on the Chinese foreign affairs and public security ministries to give her a passport, trying to convince them that it was in China’s interest to let Liu Xia go.

Kinzelbach said other diplomatic efforts included formal protest notes or requests, negotiations between diplomats and state leaders during visits or summits as well as briefings by the German Federal Foreign Office to other ministers in the hope they would bring the issue up on their visits to China.

Liu Xiaobo’s widow briefly emerges from house arrest during national holiday

It appeared to pay off. In September, Chinese security police made the first of a series promises to Liu Xia that she would be allowed to seek medical treatment overseas if her brother Liu Hui stayed behind and they “cooperated”. It was a coded offer – if her family, her friends and the diplomats working on her case kept quiet the Chinese authorities would live up to their word.

There was cause to believe in the quiet approach.

According to Kinzelbach, Germany began engaging in a rule of law dialogue with China as early as 1999 and a bilateral human rights dialogue in 2003. The first release of a political prisoner occurred in 2005, when dissident Wang Wanxing was released. Wang had been locked up for 13 years in detention centres and psychiatric institutions before he was allowed to go into exile in Germany.

Germany, US renew calls for release of Liu Xiaobo’s widow from house arrest

His release helped to convince the German side that quiet diplomacy was a mutually beneficial negotiation model.

“[The Chinese] always say quiet diplomacy works best to resolve differences, so if you stay quiet in public, they promise to stay cooperative,” Kinzelbach said.

But for quiet diplomacy to work, some concrete actions had to be taken “to prove that it is working, to convince your interlocutors that it is worth the effort” and “to keep the diplomatic apparatus busy and somehow satisfied”, she said.

“Of course, if there is no public pressure, then there is no incentive to act, and nothing happens. That means, you need to skilfully combine quiet diplomacy with public pressure – you really have to show that you are willing and able to escalate the problem. That’s precisely what the German ambassador did in the case of Liu Xia.”

THE LAST PUSH

However, each of Beijing’s promises was met with disappointment. In February, a senior Chinese police official visited Liu Xia and Liu Hui during the Lunar New Year and promised that she could leave China by the end of April after the annual parliamentary sessions. They were so confident that this was this as it that Liu Xia packed her bags and said goodbye to her friends.

When those hopes faded, German ambassador Michael Clauss changed tack and made a public call for Liu Xia to receive medical treatment overseas in an exclusive interview with the Post in late April.

The month came and went and still Liu Xia remained confined to her Beijing home.

The disappointment was devastating. Liao was also sick of waiting quietly and released a recording of a phone call in which Liu Xia said she was ready to “die at home” in protest.

By then, Berlin was more or less alone in its campaign.

“In response to this and to further step up pressure, Chancellor Angela Merkel raised the case with President Xi Jinping during her visit in May,” Kinzelbach said.

“I believe when Merkel came to China in May, she made it clear that Liu Xia’s case was a personal concern.

“At the level of chancellor, Germany can only raise utmost priorities, usually this means just one single case. She directly talked with Xi Jinping during her last visit. I would imagine she did it in a non-confrontational manner but the fact that she did it at all probably shocked him. No one else is doing it,” she said.

Merkel’s trip to China was believed to be pivotal – after her visit, China made a new promise to Liu Xia that she could leave China by the end of August.

“Chancellor Merkel seems to be really committed in this personally because of her background as she grew up in the former [East Germany]. She was also part of the civil movement for peaceful revolution in East Germany,” Shi-Kupfer said. “She … has a really strong commitment to human rights, justice and freedom.”

Liu Xia’s friends ‘planning meeting’ with former German president Joachim Gauck about her brother’s case

The August promise was met with scepticism but everything changed after Liu Hui, who had been released on medical parole, received a sudden phone call from Chinese police on July 4 that a passport was finally being issued to Liu Xia.

She had it in her hands two days later and a German visa was organised the same day. But few knew of the arrangements – even her older brother Liu Tong did not know she was leaving until after her plane left Beijing airport at around 11am on July 10.

While Liu Xia was in Berlin for the first anniversary of her husband’s death, Liu Hui remains in China, unable to leave because of the cloud hanging over his legal status.

In the two weeks since, Liu Xia has said nothing, apparently keeping up her own form of quiet diplomacy.