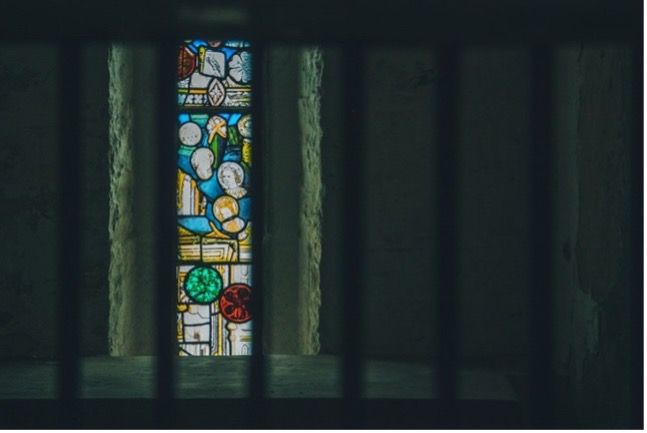

監獄作道場——《Man’s Search for Meaning》

[按:由於網媒如《立場新聞》《眾新聞》已於早前停止運作,我把從前登載在此等媒體之一些文章(或少量早前投稿但未被接納登載的文章)重新發表於此,本文屬其一。]

「我而家當喺修道院,當係修練」,黎智英如是說——他對自己的當下苦況賦予了重要的意義。

這讓我想到Viktor E. Frankl的名著,《Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy》(有中文版);此書是關於作者自己於納粹集中營的親身經歷、此經歷與其發明「意義治療」(Logotherapy)的關係,以及意義治療的核心思想。

此書的第一部分(我手上的版本是1984年的第三版,正文共有三部分),〈Experiences in a Concentration Camp〉,的首段是這樣寫的:

This book does not claim to be an account of facts and events but of personal experiences, experiences which millions of prisoners have suffered time and again. It is the inside story of a concentration camp, told by one of its survivors. This tale is not concerned with the great horrors, which have already been described often enough (though less often believed), but with the multitude of small torments. In other words, it will try to answer this question: How was everyday life in a concentration camp reflected in the mind of the average prisoner?

它的第二部分,〈Logotherapy in a Nutshell〉,的最後兩段說道:

A human being is not one thing among others; things determine each other, but man is ultimately self-determining. What he becomes—within the limits of endowment and environment—he has made out of himself. In the concentration camps, for example, in this living laboratory and on this testing ground, we watched and witnessed some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints. Man has both potentialities within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions but not on conditions.

Our generation is realistic, for we have come to know man as he really is. After all, man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord's Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips.

於第三部分(1984年版本新加的一個後記),〈The Case for a Tragic Optimism〉,的開首,Frankl寫道:

Let us first ask ourselves what should be understood by "a tragic optimism." In brief it means that one is, and remains, optimistic in spite of the "tragic triad," as it is called in logotherapy, a triad which consists of those aspects of human existence which may be circumscribed by: (1) pain; (2) guilt; and (3) death. This chapter, in fact, raises the question, How is it possible to say yes to life in spite of all that? How, to pose the question differently, can life retain its potential meaning in spite of its tragic aspects? After all, "saying yes to life in spite of everything," to use the phrase in which the title of a German book of mine is couched, presupposes that life is potentially meaningful under any conditions, even those which are most miserable. And this in turn presupposes the human capacity to creatively turn life's negative aspects into something positive or constructive. In other words, what matters is to make the best of any given situation. "The best," however, is that which in Latin is called optimum—hence the reason I speak of a tragic optimism, that is, an optimism in the face of tragedy and in view of the human potential which at its best always allows for: (1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life's transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action.

在這個香港抗爭者動輒會被拘捕被囚禁被失蹤的苦難時期(在緬甸,還會被公然謀殺!),相信這本書有一定的參考價值。Frankl喜歡引用尼采的一句名言:「He who has a why to live can bear with almost any how」;相信每個人亦可從自己的生活中舉一些覓得意義而有助克服困苦的例子,但真正的考驗在於當突如其來的巨大苦難降臨時,仍能尋獲並且肯定堅持承受的重要意義。