Report on Current Situation Facing Chinese Youth Activists

Report on Current Situation Facing Chinese Youth Activists

(Click here to download the report)

Table of Contents

II. Methodology, Definition of Activists, and Major Findings

1. Research Methods and Definition of Chinese Youth Activists

III. Profile of Youth Activists

1. Paths to Public Interest Work

3. Learning Styles and Risk Mitigation Techniques

IV. Challenges Facing Youth Activists and Impact on Mental Health

2. Lack of Resources, Slowing Growth

3. Internal Conflict within Activist Groups

4. Vulnerability of Individuals under Multiple Pressures

V. Views on Activism and Politics

2. Declining Approval of Government

3. Split between Theory and Practice

4. Complex Relationship to Democratic Values

1. Supportive Environment and Effective Communication

2. Opportunities for Learning, Skill-Building, and Mentorship

I. Background

Since 2003, China’s economy has experienced rapid growth, while politically the country has been fairly open. Despite constant back-and-forth between the government and citizens, on the whole civil society has grown in strength. Under these favorable conditions, a whole crop of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and citizen groups have emerged, especially between 2008 and 2013, including rights-based NGOs and activist networks. Many idealistic young people have joined these groups and NGOs, getting involved in a great variety of public interest work and effecting real change at different levels of society. A youth activist community, whose ranks continue to grow but whose borders are unclear, has taken shape.

However, for reasons political, economic, and global, in 2013 the Chinese government started to reinforce ideological control and progressively clamp down on the political space. A series of political crackdowns on rights-based NGOs and citizen groups occurred from 2013 to 2015, including the series of “shutdowns” of the public health and social justice NGO Yirenping in 2014, an organization which had an enormous impact on the field youth activism; the detention of the “Feminist Five” on the eve of International Women’s Day on March 7,2015, known as the “Three-Seven” feminist incident; arrests of anti-discrimination workers; the nationwide detention of hundreds of human rights lawyers and activists starting July 9, 2015, often referred to as “Seven-Oh-Nine”; and the detention of key labor activists in Guangzhou on December 3, 2015, or the “Twelve-Three” incident.[1] This violent suppression by the combined forces of the government and the state continues to the present. For youth activists who are fairly young and have very little experience with Chinese politics, this is a hard blow at the very outset of their careers.

It seems that the field of social activism in China has entered a fallow period. Against this backdrop, what difficulties are youth activists facing right now?

Through in-depth interviews with 36 youth activists, this report attempts to describe the many-layered circumstances in which youth activists have found themselves since 2015, as well as their mental state under these difficult circumstances. On this basis, the report further seeks to explain how changing circumstances over the past few years have influenced youth activists' understanding of politics and activism, and to tease out what they most need at this time. Research for this report began in January 2018 and was completed in December 2018, taking place over the course of a year. Through this report, the research team seeks to increase global understanding of youth activists in China, and in doing so bring them potential assistance and support.

II. Methodology, Definition of Activists, and Major Findings

1. Research Methods and Definition of Chinese Youth Activists

This study utilizes qualitative research methods. The research materials were gathered from interviews. The interviewers followed an outline jointly formulated by the research team and the principal investigator. Interviews took 2 hours on average. The outline served as the basic framework for the topics covered in the interviews. Outside of this framework, there was limited flexibility on the subject of our conversations. Aside from the oral content obtained during the interviews, the interviewers’ notes were also used as reference materials for this study. All interviews were completed by March 2018.

The majority of youth activists we interviewed for this report work on labor and gender issues; others are involved in environmental protection, disability rights, and other issues. The interviewees are active in Guangdong Province (which includes the cities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan, Dongguan, and Zhongshan) and the cities of Beijing, Wuhan, Hangzhou, Xi’an, and Lanzhou. In terms of age distribution, 83% of interviewees are 25-35 years old, 14% of interviewees are 36-45 years old, and 3% are in other age groups.

Prior to beginning our research, it was first necessary to clarify the parameters defining our subjects and the representativeness of our sample. When selecting interviewees, we focused on activists who had already experienced some form of suppression. In other words, our subjects comprise a more “radical” group of activists chosen from among the already “radical” community of “citizen youth activists.”[2] The term “citizen youth activists” as used in this report primarily refers to young people at a certain stage in life who have been significantly involved in community organizing, protecting the rights of marginalized/vulnerable groups, or campaigning on issues of public interest. In this context, “civil society” refers to a system that is relatively independent of the state and the government as well as market forces, and is comprised of a network of wide-ranging grassroots organizations and volunteer activists. The definition of “marginalized/vulnerable groups” depends on the structural issues facing a given society. Among the vulnerable populations youth activists are concerned about are laborers (seasonal and long-term migrant laborers from rural areas) disabled people, and sexual minorities. The scope of “public interest” is broad, including issues such as environmental protection, social services, and the use of public funds. By emphasizing participation in these tasks as their “primary occupation,” we may easily distinguish youth activists from the large number of young people who occasionally volunteer in actions or who participate in public discussions online. The vast majority of the young people from whom we collected our sample have experience working full-time in grassroots organizations, such as NGOs. Given the diverse forms of engagement in civic action, a portion of our sample group naturally included those who have always worked independently. We emphasize “a certain stage of life” in order to highlight the unsettled nature of this group. Some young people, once they set foot in citizen action, will continue on this path, and some aspect of this work will become their life calling. Others will leave activism after several years for jobs in the for-profit sector, or will return to school to pursue advanced research. “Youth” is also a relative concept. We had no strict age threshold for selecting our subjects, but we did look for people in that crucial phase when they enter society (mainly 30 or younger) and who had begun to engage with social activism.

2. Major Findings

Our study found that the vast majority of youth activists become involved in advocacy out of concern about social inequality. A small number were drawn to the movement by idealistic hopes of changing the sociopolitical system. Their work primarily centers around a single issue, from which standpoint they advocate for the rights of vulnerable populations and promote social progress; once the political crackdown intensified, a portion of our subjects also became involved in helping political prisoners. In general, their work and activities are not overtly political. For the most part, their actions and opinions do not tend towards any “red lines,” such as challenging the legitimacy of the Communist Party or the political regime, ethnic separatism, or Taiwan independence. Our study of the subjects’ personal development also showed that the vast majority of young Chinese activists lack systematic support in their daily work and lives, and that their capacity to respond to and manage political risk is fairly rudimentary.

The most serious problem they face is the relentless escalation of political risk. 94% of interviewees have encountered varying degrees of political suppression. Consequently, the organizations and groups in which youth activists take part have stalled in a period of low growth due to a lack of funds and manpower. Youth activists themselves face a whole host of vulnerabilities, such as economic insecurity, lack of family support, precarious institutional support, and a dearth resources for mental health. They often must bear political risk alone. Add to this that they cannot see any prospects for their personal economic or professional growth, and the result is widespread depression and other mental health problems. As external pressure builds, it becomes more difficult to mediate conflict within activist groups. These internal problems can easily be the last straw for already-stressed youth activists, overwhelming them and harming their mental health. Youth activist groups are fragmenting, and the attrition of individual activists is accelerating.

The general consensus among youth activists is that the activist movement is currently at a low tide. They believe the rise of political risk, the degradation of the space for public discourse, the government’s proliferating tactics of control, and the fragmentation of activist groups are the main reasons why social activism is unable to move forward at this time. Nevertheless, most activists do not want to give up, and are continuing their public interest work despite the difficulty of their situation. At the same time, their approval of the political regime has dropped significantly. For a portion of youth activists, their views on the movement and on politics have radicalized, while their outlook for Chinese society has become even more pessimistic. Amid general hopelessness, youth activists’ plans for the future appear to be to “hibernate” and wait. This study also attempts to understand youth activists’ views of democracy, and finds that they still identify strongly with democratic politics.

Youth activists are in need of a supportive group environment, opportunities to build their knowledge base and skill set, and funding and manpower. Among these needs, a supportive environment consists of three elements support and trust within activist groups, friendly association among the various activist groups, and continued communication between activist groups and society at large. Knowledge and skill development include professional skills, analytical skills, and improvement in the capacity to respond to risk. Since the government crackdown worsened in 2015, many activists also hope to benefit from studying overseas.

III. Profile of Youth Activists

This section describes and evaluates youth activists as a group based on what leads them to invest themselves in public interest work, how they generally work, how they learn, and how they mitigate risk.

1. Paths to Public Interest Work

The average age of the subjects of this study is 29.6 years old. The subjects were born and grew up during China’s “stable period” of rapid economic growth and gradual social opening. Compared to their predecessors, who were born in the 1960s and 70s, youth activists' perception of issues in the political system stem from their everyday lives, rather than major political events, and are therefore more inclined to concentrate on very specific problems. Youth activists’ motivations for working in the public sphere may be put into three categories: the most common is concern about the rights of vulnerable groups and sustainable development; the next most common is that they themselves or someone close to them has dealt with infringement on their rights; there are also a small number of young people who become involved out of concern about the political system.

Due to their self-motivated interest in and pursuit of social justice, once an opportunity presents itself—such as a program to promote educational equality, an NGO platform, a case of rights violation, or a relevant course of study—young people take the initiative in launching or participating in actions Many of the interviewees were exposed to civic actions through various community activities during their time at university. These seemingly ordinary community activities can motivate college students to participate in civic action because they are often linked to a broader network of activists. This network includes organizations that have successfully registered and received government approval, as well as unregistered organizations and groups which nonetheless have not been directly rejected by the authorities. These organizations often focus on social issues, adopting a fairly progressive stance. Through participation in training camps, discussion groups, and other activities, young people come to realize that the issues they care about are rooted in society. Consequently, they are willing to invest in civil actions that exceed their own self-interest. For example, a student who is interested in gender issues will often meet activists and intellectuals from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and even overseas through activities on and off campus. They become conversant in the discourse on feminism and gender studies, transforming into activists through the participation and practice. There are also young people who learn about the grassroots by taking part in collective action. For instance, some youth in the Guangzhou region have become interested in labor issues through their participation in collective rights defense with sanitation workers, gaining deeper awareness of social problems from this activist network.

Some young people are motivated to protect their own rights and those of the people around them. These youth activists or their close friends or relatives have been personally effected by inequality—such as discrimination due to an illness or disability or because of their gender, or an issue of labor rights—and after advocating for this particular issue, decide to continue their work to protect the rights of those in their community.

Then there are those young people who, prior to entering into public interest work, have thought deeply about political and social issues. They join the movement with big-picture aspirations for social and political reform, and are more attuned to current events and the theory behind political issues. However, they have relatively few options outside of institutional forms of public interest work. They primarily get their start in NGOs working on specific social issues, such as countering discrimination or environmental protection. They may switch to a different issue or start working on a trending issue if presented with a new opportunity or a change in circumstances.

In general, youth activists are spurred to action by concern for social justice and social progress. Their work is concentrated on specific social issues, including gender equality, labor rights, and environmental protection.

2. Work Methods

The activists we interviewed have a variety of work methods, which we have put into simple categories: The most common method they have used or currently use is to develop workshops and trainings for different social groups, targeting different issues. The next most common is advocacy work within the parameters of the Chinese government, including policy research and proposals, letters to the delegates of the National People’s Congress (NPC), lawsuits, and applications for open information; followed by public “performance art,” services for social groups or communities, research on social issues, work on representative cases, independent media, labor rights campaigns, and so on. A small number of activists have also run as independent candidates for the first rung of the NPC, participated in street protests, or operated youth spaces. Regardless of whether or not they are identified with an organization, the vast majority of youth activists draw from intersecting methods in their specific work; very few use just one, opting out of other work/actions. As political pressure has increased, nearly one in three interviewees have also come to the aid of political prisoners.[3]

In general, the interviewees had achieved some success and have had a significant social impact in their respective fields, including promoting substantive policy changes; managing an iconic organization or public space; organizing dozens or even hundreds of people in a collective action; gaining widespread coverage in mainstream media, both in China and abroad; garnering a high level of international attention and recognition; training a certain number of next-generation activists; and organizing influential campaigns of support for political prisoners. It is fair to say that a considerable proportion of the respondents in this survey are the iconic figures in their field.

Overall, the survey respondents are distributed across the spectrum of Chinese social activism, from “moderates” to “radicals.” However, the proportion of interviewees who are more “radical” far exceed the proportion in the world of NGOs and civic groups more generally. Therefore, this study may be considered to be a fairly complete distillation of the experiences, thoughts, feelings, and circumstances of youth activists across the spectrum of Chinese activism, but does not necessarily represent a corresponding proportion of the Chinese youth activist community.

The approaches of the youth activists we interviewed all exhibit three characteristics:

1) The vast majority of youth activists take a progressive approach to social issues. From empowerment training, policy advocacy, and performance art, to labor movements and independent campaigns for office, activists want to change structural inequality and to promote laws and policies. Politically, their work focuses on reform, rather than resistance. A small proportion of activist work, such as running independent media and operating youth spaces, is relatively neutral. Individual youth activists have participated in street protests, showing a certain degree of resistance to the political system. Providing assistance to political prisoners also has a certain sense of resistance about it, but the vast majority of youth activists who have provided aid did so after they themselves or their partners were caught in the political crackdown. At the same time, there is an element of humanitarianism to this work. Apart from helping political prisoners, this group of young people has hardly participated in any other work that is overtly oppositional. One can see that the strategies, techniques, and established public forms youth activists adopt are essentially aimed at achieving social progress and promoting real and effective social change; the decision to publicly take a political stance or to directly criticize the government or the regime is based on strategy, not principle.

2) Youth activists are generally professionalized and single-issue focused. This is not to say that all young people who enter into the field will settle into activism full-time. From their first taste of activism to their decision to identify as activists, they go through certain stages of "professionalization": volunteering—engagement with activist networks and organizations—joining an organization/group—full-time activism. Most of the subjects of this study have worked full-time for an organization or body that is focused on a particular issue. They frequently see their participation in the public sphere as an occupation that aligns with their ideals and values. As they go from being individual activists to professionals, they often choose to cultivate their career around a single issue, such as gender, labor, the environment, disability, LGBT, disease discrimination, or education; there are activists who work on intersecting issues, but they are a fraction of the group; outside of their issue-based work, the few activists who are deeply concerned with political issues will personally involve themselves in a trending issue or will quietly participate in politically-focused campaigns. This is not unrelated to opportunities in the public sphere—the political risk inherent in social “hot topics” presents itself as more direct and immediate, while organizations job opportunities in support of such activism are scant.

It is important to note that “expertise” here does not have the same meaning as in the private sector, since not all NGOs and groups are permitted to officially register. Their identity as professionals instead refers to how they organize themselves.

The process of professionalization also includes training in fundamental organizational skills, such as public fundraising, writing project applications, and organizing community training and meetings; individuals may also occasionally participate in training and exchanges related to a specific issue. Over the long term, youth activists’ single-issue work and training has often resulted in the concentration of their skills and experience in a single domain.

3) Most youth activists in rights advocacy must engage in public discourse, primarily through the combined use of social media and traditional forms of media. This need arises directly from China's political system. Without reliable and effective channels to exert pressure on the government, activists must use public discussion to gain the attention of the government, making progress through indirect means that lack clear results.

3. Learning Styles and Risk Mitigation Techniques

For youth activists, education is not only a necessity for personal growth, but is also crucial to supporting their continued participation in the public sphere. Our study shows that their educational efforts touch on four elements: methods and capacity for community organizing, analysis of social issues, theory of social movements and related social sciences, and technical skills (such as fundraising, photography, writing, collaboration, English, etc.).

However, the educational channels that have been or that currently are available to youth activists are essentially informal and unstable. Among the interviewees, the great majority admitted that they lacked in-depth understanding of their respective fields prior to starting work in those fields. This means that both the movement itself and individual activists must pay a higher “learning cost” for their limited experience and knowledge. Most said they have learned or are currently learning on the job. A fairly large number of activists also learn through short-term training and workshops, self-study, and conversations with their peers and senior activists. These learning methods are not systemic and have limited results.

With the tightening of the space for activism after 2015, many youth activists now hope to advance their knowledge and analytical skills by studying abroad, which would also shelter them from risk. However, the prerequisites and high financial costs mean that their willingness to study abroad does not equate with the means to do so.

Youth activists who are just starting out employ fairly rudimentary methods of risk management. Youth activists primarily rely on three main forms of risk mitigation: information security for internal communication (such as using encrypted messaging applications and non-Chinese email accounts), self-censorship (not engaging in riskier work or not making public their participation in such activity), and transparency in their activities (making the substance of their work available to the public, including the police, and canceling plans if the police disapprove). As political risk and police surveillance have soared, the latter two tactics have greatly reduced the ability of youth activists to take action.

As one can see, the youth activists we interviewed begin with a general sense of how to manage risk but a limited ability to respond to risk. This has resulted in blatant suppression of many activists under the worsening political environment. The majority of the activists surveyed have experienced low to moderate push-back, including suspension of activities, phone calls from the police, interrogation, forced relocation, and pressure in their workplace. Some have endured much worse, including detention, court sentences, and the closure of their organizations. The crackdown has been a huge blow to youth activists’ future in the field, as well as to their mental health.

IV. Challenges Facing Youth Activists and Impact on Mental Health

The challenges Chinese youth activists face stem primarily from the escalation of political pressure in recent years. The unfavorable political reality has lead to a lack of resources at these activists' respective organizations or groups, curbing their progress and preventing youth activists from advancing their careers and earning a living; the unfavorable political environment and work conditions have left youth activists with acutely poor economic, familial, and public support. In this vulnerable state, the proportion of activists suffering from clinical depression is fairly large; in addition, internal conflict within the movement is often difficult to resolve in a short period of time, pushing idealistic, energetic young people away. Fragmentation is often seen within activist groups.

1. Escalating Political Risk

The challenges Chinese youth activists face stem primarily from the escalation of political pressure. Over the past few years, about two-thirds of interviewees have encountered various levels and types of harassment from the authorities (primarily the police), reaching into their professional and personal lives. They are harassed both within and beyond normal enforcement of the law, most often in the forms of censorship, interrogation, and demands to cease activities.

As China’s political reality increasingly limits the forms movements can take (for example, the government has employed a series of tactics to restrict citizen organizing, assembling, and demonstrating), the vast majority of youth activists must work through online platforms or the mainstream media system in order to influence public opinion to advance their demands/reach their goals . With the restriction of speech since 2013, it has become increasingly difficult for youth activists to garner the attention and exposure of the mainstream media. Even “self-media” channels such as WeChat, Weibo, and other social media platforms are subject to rigorous and meticulous censorship and frequent deletion of posts and accounts. Activists working in independent media said that it has become routine for them to “forget how many of their accounts have been deleted” and to see their most effective content removed or blocked; after the implementation of the real name registration system, they have had even more problems signing up for new accounts. Furthermore, online communication can also lead to offline harassment. A portion of activists were interrogated or pressured by the police or their schools after they had signed an online petition or reposted an article about a current event. The censorship brought about by the tightening of the political space has led to a sharp decline in the visibility and influence of youth activists in mainstream society.

The encroachment of the police into activists’ work and even into their personal lives has markedly increased in recent years. Some activists described the intensity of this harassment as “endless.” On the one hand, the police’s tolerance for activist work has significantly diminished: activities which the authorities have allowed in the past, such as petitions, lectures, writing, and various types of meetings and training camps, can now lead to inspection, interrogation of the person responsible for the activity, or a forced stop to the activity. On the other hand, causes that were previously acceptable, such as women’s rights, LGBT rights, environmental protection, disease discrimination, and labor rights, have by turns been cracked down on, suddenly increasing the political sensitivity of these issues. Several activists mentioned that if the authorities simply observed a “sensitive person” participate in a given activity, the organization/organizer of that activity would be subject to police investigation or forced to stop the activity altogether. This has also led different activist groups to censor themselves and censure other groups for their sensitivity, creating an atmosphere of mutual judgment and isolation.

Another common form of harassment is “forced relocation,” using intermediaries and landlords to threaten and prevent activists from continuing to rent their homes or offices. This not only uproots activists, but also hurts them economically by depriving them of their deposits; forced relocation also sows conflict in activists’ daily interactions with landlords, neighbors, roommates, and even family, leaving them with a heavy psychological burden and a sense of instability.

In addition to the routine measures mentioned above, since 2013 youth activists have been targeted with forms of political suppression which previously would have not been visited on them, including restrictions on personal freedom, forced closure of organizations, and harassment of activists’ family. Many activists admit that the pressure on themselves and their work partners has far exceeded their expectations. Nearly one third of interviewees have experienced situations in which their organization was shut down or their property was confiscated, their family members were harassed, or they or their colleagues were detained by the police and convicted of a crime. Almost every one of these activists had not been detained prior to 2013; many were first detained in or after 2015.

Such crackdowns are likely to be devastating to an activist, an organization, or even a particular cause. Most of the activists who have experienced suppression have difficulty continuing their work over the long term, or must significantly reduce the intensity and visibility of their work. The shuttering of organizations also robs activists of a stable, collaborative platform, forcing them to disperse. Nearly everyone who had encountered official retaliation showed the symptoms of trauma, such as anxiety, fear, vigilance, and depression.

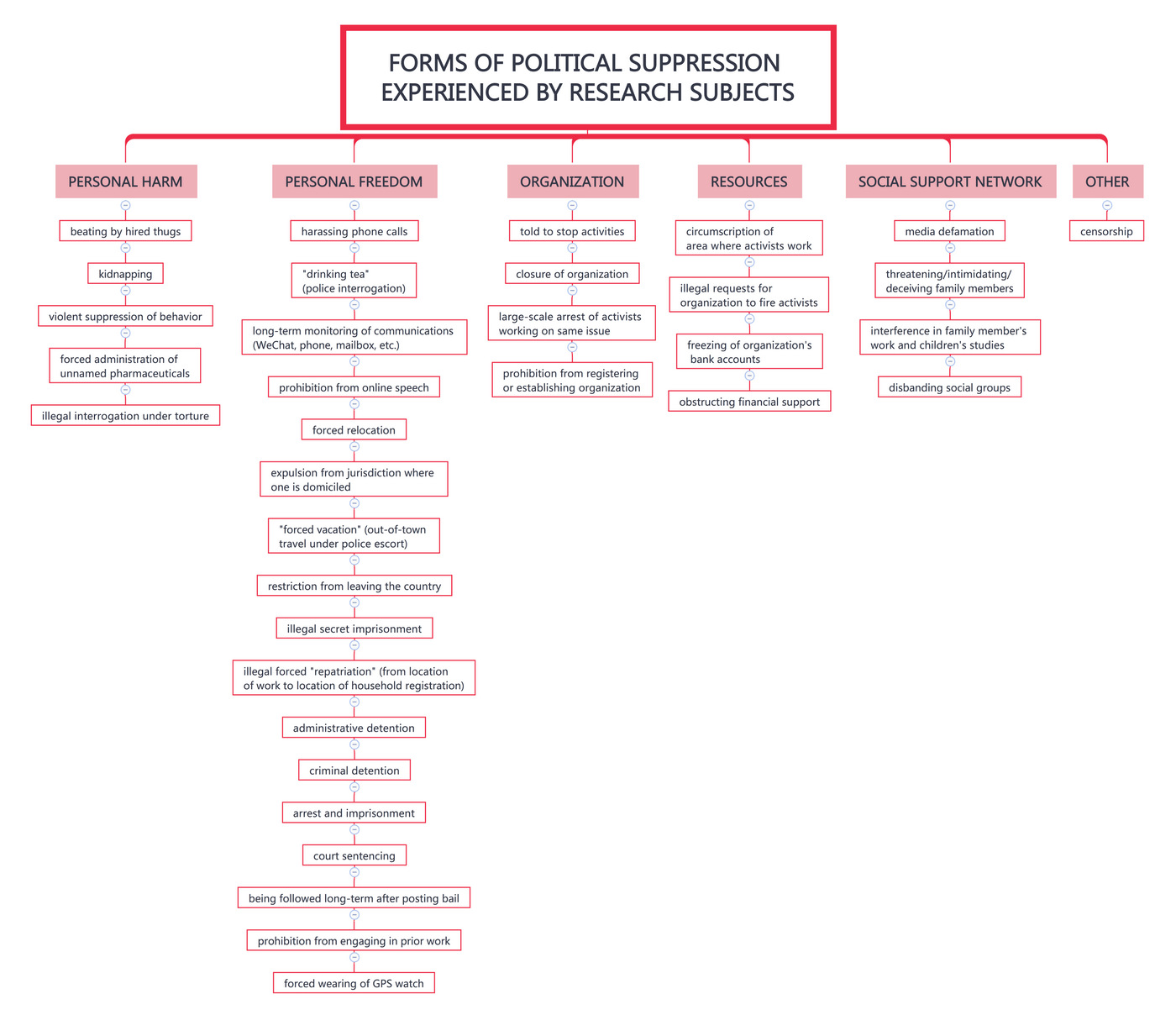

We have combed through the incidences of political suppression the research subjects experienced, from which one may see that the diversity and intensity of these tactics are impossible to stand up against.

As the crackdown continues, some of these activists have begun to rethink how they manage risk and to reconsider the logic behind the government’s suppression of civil society, as well as its trajectory. Funders have also started to attach importance to training projects addressing the crackdown.

2. Lack of Resources, Slowing Growth

The deterioration of the political environment has lead directly to a resource shortage for activist groups most notably a lack of funds and manpower.

The promulgation of the Charity Law and the Law on Administration of Activities of Overseas Nongovernmental Organizations in the Mainland of China (Foreign NGO Law) on September 1, 2016 and January 1, 2017, respectively, have had a direct impact on the funding opportunities available to civil action groups, turning the screw even tighter on grassroots rights advocacy organizations. Charitable foundations have flourished in China over the past decade. However, youth activists involved in civic action, especially of a more progressive and confrontational nature, have not benefited much from this charitable expansion. In this restrictive environment, domestic funders have increased self-censorship and keep a “respectful distance” from rights-based organizations and groups. At the same time, some international funders that were previously more active in supporting rights-based groups in China have significantly reduced their investment in order to gain legal status for activities in mainland China. Crowdfunding, which has grown in popularity in recent years, is not much help to youth activists, since the broader public has a limited understanding of the work they do. These pressures are sapping the energy of youth activists.

The dearth of funding sources has financially cut off some activist and rights-based organizations, and many activists have labored without compensation or do not have a stable income. The funding problems of individual organizations continue to be unresolved, leading to a reduction in personnel and projects. If they are cracked down on again, they will often choose to close their doors. Although some organizations or groups with more resources use all means available to them to maintain capital flow, it is still difficult for them to develop and grow, impossible to give anyone a raise the salary, and thus also impossible to attract new talent. Other rights-based institutions have tried to adjust the nature of their work and launch projects that will be acceptable to the government and domestic foundations.

Over the past 4 years, the shortage of funds, lack of manpower, and intermittent political interference have slowed the growth of the entire nonprofit sector. At this time, many youth activists are solely responsible for managing a project as soon as they enter the sector. While such experience can quickly bring them a sense of excitement and accomplishment, the lack of resources often means that their organization or team cannot continue to supply them with work opportunities or support, funds for education, or opportunities for advancement.

In the current low tide of the movement, many activists still hold on tightly to their ideals and their hope to stay in the nonprofit sector. However, the long stretch of time without professional growth or increased income, as well as the lack of effective and systematic professional support from outside of the field, can erode the enthusiasm and confidence of those just starting in activism.

3. Internal Conflict within Activist Groups

Just as in other fields of work, questions of power relations and unequal distribution of resources can create conflict within nonprofit organizations. Most youth activists come to the movement with ideals of social equality and public participation, and are particularly sensitive to, and critical of, inequality. When it comes to unfair and undemocratic power dynamics within their group, youth activists are more likely to notice these issues and less likely to be accepting of them. If such problems are not solved fairly and effectively, it will inevitably lead youth activists to lose faith in the movement, making it even more difficult for them to stay motivated.

Most internal conflicts spring either from ideological or strategic disagreements, or from issues with the allocation of resources and responsibilities within the organization.

In the former category, many conflicts involve the organization and activists deeming each other to be “moderate” or “radical.” For example, organizational heads who have gradually turned to more moderate platforms tend to distance themselves from “radical” or “sensitive” groups, issues, and activists. They do not give support to colleagues who have faced persecution, they leave out the discussion of rights from their own work, they ask their staff to continue to communicate and compromise with authorities, and they refuse to let activists labeled as “sensitive” by the government participate in their organization’s activities. Some activists feel let down by these leaders. This can cause resentment among activists and groups who are “kept at a distance,” and may also stir controversy within the organization. Some activists will lose faith in the organization and its leaders, believing they have violated the principles and intent of nonprofit work, and the two parties will gradually part ways.

However, ideological and tactical disagreements do far less damage than disputes over the allocation of power and resources. About three times as many interviewees were hurt by the latter as opposed to the former. Conflicts over funding and power distribution may touch upon a number of issues, such as gender and interpersonal problems within the group, disagreements over which organization is responsible for a given campaign, problems with internal communication, and workload issues.

Still, compared to the given problem itself, the way a group handles internal conflict are more likely often tear a group apart. Some activists who have been hurt by group conflict believe that the strong oppositional consciousness can easily lead to intense disagreement that escalates to the level of ideology; at the same time they are limited by the influence of the movement’s culture and by insufficient training in public discussion—the group can easily split into factions and find it hard to reconcile with each other. In the politically restrictive environment, where nonprofit organizations have trouble making ends meet, it is objectively easy for resource hoarding to occur. Once a conflict occurs, the weaker side is reluctant to share resources. Marginal and low-growth groups also lack a system of mediation, often forcing the weaker party to face out of the “circle.”

When the rewards are so grossly disproportionate to their effort over the long term, it effects youth activists' motivation to continue their activism and their sense of belonging. The disappointment brought by group conflict can also be the final straw that breaks them psychologically.

4. Vulnerability of Individuals under Multiple Pressures

The lack of resources and slowed development of their profession has weakened youth activists in terms of their economic security, family relations, ability to bear risk, and mental health.

Income from nonprofit work often covers only basic needs. The majority of activists have gone without pay for some period of time or have been forced to rely on family funds, while others have spent down their savings. While a portion of organizations are able to purchase basic social insurance for their employees, most activists do not have access to insurance, either because their employment is unstable or because their organization is unable to legally register. Activists who have just graduated from university may accept lower pay out of their faith in, and enthusiasm for, the ideals of social movements. As activists get older, the demands on them grow, from paying rent and building a household to raising their children and leading a stable life. At the same time, the gap will continue to widen between their incomes and those of their peers in mainstream industries. Youth activists will feel increased pressure and will start to think about changing careers. The attrition of senior staff exacerbates the low level of growth in the sector, creating a vicious cycle.

Pressure from family members is also difficult to avoid. It is difficult for mainstream society to understand the direct and indirect political risk inherent in activism. Most youth activists’ parents do not support their children’s work, and it is rare for youth activists to have good family relationships. To lessen their parents' concerns and prevent parental interventions, some activists have no choice but to conceal the true nature of their work; while there are also a few parents who accept their child’s social ideals and career choice, they inevitably worry about their child’s safety. Several interviewees revealed that the police had pressured or threatened their family members in order to force them to stop their activist work.

External pressure also affects intimate relationships. Many activists, consciously or not, find their partners and develop intimate relationships within their group. To a certain extent, being in the same environment can promote mutual trust and mutual understanding: in fact, during our interviews a number of activists said that they received the most care and support from their partner. But for others, working in the same field as your partner is more like a nightmare. Differences of opinion on politics and methods of activism between partners can build tension and magnify each other in a constrained environment. This has harmed many activists.

It is important here to point out that past experience has shown that no matter how much support a group can provide, political suppression is aimed directly at the individual activist, and that individual must bear the burden themselves. This is a weighty test for a youth activist. In recent years, mental health support geared toward the trauma of political suppression (as well as the aforementioned trauma of internal division) has been extremely limited. The vast majority of youth activists get through their mental crisis on their own, through patience, exercise, confiding in a companion, or by consoling themselves.

Squeezed on all sides by these pressures, youth activists cannot avoid their worsening vulnerability. An obvious outcome of this situation is the large proportion of youth activists who have developed some form of depression since 2015. Nearly half of interviewees mentioned that they were under enormous psychological pressure (stemming from fear of state violence, anxiety about their inability to get more support, and doubts about the value of their activism) and that they are prone to feeling powerless, confused, and lonely, perceiving themselves as marginalized and unsupported within both the activist community and in mainstream society; almost 20% of interviewees have been clinically diagnosed with depression and require medication and counseling.

V. Views on Activism and Politics

“We are in the winter of activism”—this is the general consensus of Chinese youth activists on the current state of affairs. This “winter” has been brought on by political austerity and a series chilling effects. While activists do not speak lightly of giving up, the ties within activist groups are nonetheless weakening during this “winter.” At the same time, youth activists’ approval of state power has sank, and their political views are becoming more radical. They are pessimistic about the future of Chinese society, expressed in their real work and individual plans as “hibernating and waiting.” A portion of activists have also been thinking more deeply and critically about democratic politics and social ideals.

1. Not Resigned to “Winter”

This study found that the most common view of the current political situation is this: the government’s authoritarianism has grown stronger, while its tolerance of the grassroots and of dissent has declined, and the space for civil action continues to shrink; therefore, the conditions for activism are fundamentally lacking, and the movement is in a difficult period of “low tide.” Nearly two thirds of interviewees expressed this type of judgment, emphasizing different points in their characterization of “not having the right conditions”: political risk is high, the environment for public discourse is poor, government controls are increasing, funds are lacking. The issue of funding is described in Section III of this report and will not be repeated here.

High political risk mainly refers to the increased risk of activists being detained and harassed and of their organizations being shut down. A number of interviewees said that the successive detention of activists over the past few years has greatly impacted their evaluation of risk, as well as their mental health. At the same time, they believe that the suppression of civil society will continue, that “this really is winter.” Some activists pointed out that because the risk involved in organizing work is so large, their team has now adopted an online action plan, but is not carrying out serious mobilization efforts. Even so, the results of this method are not consistent. Some interviewees who work on labor rights said that is basically impossible to organize workers at this time. Many others noted that the government’s “red line,” which previously was fairly obvious, is now almost impossible to discern. Some activists are starting to think of the crackdowns and the sacrifice of personal freedom as the price that must be paid to sustain the movement and their social ideals.

One interviewee told the survey team, “The government’s control over public discourse has just ballooned… It’s like an unknown creature, evolving in ways we couldn’t imagine.” Aside from online censorship, deletion of content, and closing of social media accounts, some activists who have paid particular attention to public discourse said that the lack of a stable, open space for discussion has changed the rules for self-media, which measure their success by the level of audience engagement. Many traditional values and commonly held ways of thinking have become impossible to dispute, and there is no way to have reasoned, reciprocal conversation. This is extremely detrimental to raising public awareness about discrimination and similar issues. Activists often fall into the trap of being smeared by official and mainstream media as “anti-China” forces. At the same time, content that aligns with modern values, such as liberty and equality, may be deleted. Independent “self-media” have trouble building their readership, and their social media accounts could be expunged at any time. This makes it impossible to effectively disseminate clear information. Rights-based organizations or groups have no advantages with self-media—it is almost impossible for them to reach the public under the current restrictions.

Activists’ feelings about the government’s increasing controls are even more predictable. On the one hand, police surveillance methods. Have advanced. Some activists have long been tracked, expelled, and monitored, and have faced the prohibition of their activities, all of which seriously influence their ability to continue their work; some organizations strictly censor themselves in order to maintain their legal status, weakening the force of their actions. On the other hand, the advancement of government management and control are also reflected in the diversification of repressive measures, such as using schools to put pressure on activists involved in particular incidents, and working with self-media to discredit rights-based organizations and activists. Several activists pointed out that, as the movement has hit low tide and activist groups face shortages of resources and energy, organizations are losing their appeal for youth activists, and have had few newcomers in recent years; they are also losing their platform for speech, inevitably putting them out of sync with mainstream society.

The interviewees went a step further in articulating their worries for activist groups: “There’s a strong feeling of being scattered, of circumstances scattering us.” Under intense political pressure, activist groups that differ on matters of philosophy, focus, and methods are pushing each other away and siloing themselves; activist groups that have been cracked down on are breaking apart from the inside; and groups that have not yet been pressured are also being weakened by the drop in vitality of the movement. Many of the subjects we interviewed expressed hope that in their future work they will consciously maintain their connections in the activist community, while also promoting cooperation and communication among different issue groups.

A number of interviewees said that the severity of this “winter” continues to exceed what they could have imagined, often making them feel helpless and hesitant. However, many activists do not want to “resign” themselves to this:

“Under this [China’s] centralized system, there is basically no space for activism [like there was before], but as an activist who has been involved for so many years, I feel that I still want to do something.”

“Maybe if you’re just starting out you may want [to take a break], but if you’re already closer to 30 years old, there’s no need to run away. This [civil action] is what you want to do.”

“If [the activist community] scatters, it will be scattered forever... [so] we have to stay together, no matter what. As soon as we scatter, it’s over.”

2. Declining Approval of Government

Before the crackdown on civil society began, the vast majority of activists came to the movement hoping to solve social problems. They attributed these problems to shortcomings in policy, poor governance at the local level, or the influence of vested interests on policy making. For the most part, youth activists diverge from mainstream ideology, but few publicly disagree with the regime or the system or engage in direct opposition to the regime. On the contrary, they tend to be “politically cold.” However, after experiencing political suppression and witnessing the government throttle civil society—even though a few interviewees stressed that they are not seeking a fundamental change in the political system—over one third of youth activists are beginning to seriously question the regime. In order to protect the identity of the interviewees, idiosyncrasies have been removed from the following two representative quotations:

“When they first cracked down, I was in disbelief. How could this happen to us?… Slowly I came to accept that the government was suppressing us, that the government doesn’t like you.”

“Before, we… were [working] within a lawful framework. I still thought this crackdown on us was because of the conservatism of the local government… Later, I came to believe this was a question of the Chinese Communist Party’s power. These social conflicts, including social chaos and cracking down on us, is completely about maintaining their position of power. It’s not simply the inappropriate behavior by local governments that we have seen before.”

One can see that a portion of youth activists, after experiencing suppression and witnessing political change, have gone from disbelief, or assumption that the crackdown was an aberration, to believing that the current regime does not accept the people’s demands or their autonomy, and that the regime’s basic goal is to maintain its power. What cannot be ignored is that the increase in political pressure has prompted a considerable proportion of activists to question the regime as a whole.

Based on the shift in their understanding of the political reality, activists are also beginning to think critically about the relationship of their own work to the regime. A number of interviewees noted that, due to the authorities’ long-standing lack of awareness or interest in the opinions of the masses, past civic actions often used public opinion to force the government to “capitulate.” After the tightening of the political space, this method has become “more and more useless.” Since the power of the government and the activist community is so mismatched, the authorities are perceived as more closed-off and arrogant. Activists can no longer rouse public opinion to gain the government’s attention; the possibility of influencing the government’s behavior, or even working with the government, has practically dropped to zero. By contrast, some interviewees have noticed that some grassroots groups will now pander to the government, or even let themselves be infiltrated by the government, in order to gain access to resources.

With the deterioration of the conditions for civil action, youth activists have lost what little space they once had. Some activists who left the country to study abroad after the crackdowns began have said that China’s undemocratic political system itself has determined that there is no space for the establishment or development of civil society.

3. Split between Theory and Practice

About 30% of interviewees said that after they or their fellow activists were cracked down on, their work was viewed by others to be more politically sensitive. Their attitudes toward activism and politics have also become more radicalized. For example, some activists started to help political prisoners after their friends were detained, continuing this work after their friends regained their freedom. Compared to previous rights advocacy work, the sensitivity of these actions are clearly much higher. Additionally, when reflecting on the progress of their work, a number of interviewees pointed out that providing social services or working on individual cases are unlikely to bring about large-scale, meaningful social changes in the current climate, because without structural change, those who receive social services cannot truly improve their situation, while cases of rights violation will continue to emerge. These interviewees are losing faith in moderate actions.

At the same time, several interviewees stressed that radical actions should not be separated from civic actions. Many interview subjects feel pessimistic about the future of Chinese society, and see no possibility for China to have a democratic transition. One said, “For the mainland, if you don’t take any violent action, if you don’t make any sacrifice of blood, then you can’t really accomplish anything.” Our study suggests that after the tightening of the political space, at least a portion of activists have become more radical in their views of the movement and of politics.

However, one cannot ignore that the polar opposite opinion also came up during research. Roughly the same number of interviewees as have been radicalized argued to the contrary, “You have to learn to compromise. Don’t look at the relationship between the activist community and the authorities as a confrontation. It is more pragmatic to work with the authorities to solve specific problems.” Judging from these interviews, the activist movement could split into opposing “radicalized” and “moderatized” factions.

In addition, we must complicate and qualify youth activists’ tendency toward more radical ideas. When asked about their current plans, interviewees who expressed more radical tendencies generally were not engaging in radical actions or intending to participate in politically sensitive work. They were willing to take on more sensitive tasks when the time came, such as advocating for political prisoners, but their daily work shows a tendency toward hibernation: some have already left the country to study abroad or are planning to do so, or else plan to build their skills in other ways; some would like to work on normalizing activism, for example by raising rights-awareness among the people around them; yet others hope to take care of their mental health and get their lives back on track, to alleviate their trauma and depression, before returning to contribute what they can to the movement.

On the surface, the radicalization of viewpoints and “hibernation” of activity among these activists evince a split between theory and practice. Indeed, this split has lead to widespread depression and a sense of helplessness. While radicalization and retreat seem contradictory, there is a logic to this pairing: activists feel pessimistic and defeated, are putting their activities into hibernation, and want to wait for opportunities and save their energy. This phenomenon supports activists’ sense that the possibility for China’s peaceful transformation has plummeted.

4. Complex Relationship to Democratic Values

Our study found that youth activists have maintained their high level of identification with democratic politics and the basic values of civil society. In describing their ideals for society, the interviewees raised two concerns: one is that the individual needs to have rights-consciousness and the power to make their own decisions; the other is that the public needs channels of participation that are systematically protected. The interviewees often used words like “[political] game,” “consultation,” and “checks” when discussing democratic politics. These concepts conform to the basic elements of democracy.

Nevertheless, as much as 80% of interviewees no longer talk about “civil society,” and rarely hear discussion of civil society at work or elsewhere. The extinction-level crackdown on all sorts of activist groups has given the majority of activists personal experience of just how little possibility there is for civil society in China right now.

A number of interview subjects brought up the recent democratic crises in the US and Europe, saying these developments reflect shortcomings in the democratic system that are difficult to overcome. New ideas and vocabulary are needed to refresh the discussion. We found that Chinese youth activists do not completely idealize democratic politics, nor do they believe that democracy can solve every problem. Instead, they regard the democratic process strategically, as a necessity for social transformation in China. Some of the interview subjects suggested that at this stage, a democratic system is a prerequisite in order for the public and the ruling party to play the “political game.” Chinese youth activists do not completely idealize democratic politics, nor do they believe that democracy can solve every problem.

In addition, some interviewees challenged traditional democratic politics and civil society from the perspectives of gender and class. They believe that women, workers, and other vulnerable groups are missing from the conversation, and that traditional democratic discourse has not dealt with structural inequality.

Although the majority of youth activists are fairly simplistic in their discussions of democratic politics and social ideals, a sizable number have applied international and post-modern contexts to their complex understanding of democracy, reflecting the interlinking of international politics and social activism that is taking place.

VI. What Youth Activists Need

Faced with the closing political space and the weakening of the activist community, many youth activists intend to adopt a more defensive position. This does not mean they want to give up on their work. We asked the subjects of this study to rank their needs according to importance. Our review of their answers indicates the following hierarchy: group and team support is at the top of the list for youth activists, followed by educational resources and mental health support, financial resources and mentoring, and finally the need for risk mitigation.[4] During the interview process, the research team and the respondents confirmed the specifics of these needs. The primary needs of youth activists may be placed into three categories: first, a supportive environment and effective communication, both within and beyond their particular group; second, opportunities for learning, skill-building, and mentorship; and third, funding and human resources.

1. Supportive Environment and Effective Communication

When asked about their needs, interviewees often mentioned support from the community and for mental health in the same breath. This shows that many youth activists tend to look for moral support within their activist group. From an outsider’s perspective, this phenomenon arises from the level of difficulty activists face in seeking professional mental health treatment.

Psychotherapy is expensive. When discussing their financial difficulties, a number of interviewees specifically brought up that they are unable to afford counseling. There is also concern that counseling and mental health treatment presents personal risk in China, since therapists may be pressured by the police to disclose patient information, and because the psychiatric departments of hospitals are by nature entities of the state. Some interviewees said they were afraid to continue treatment after they or their organization’s partners had been pressured by the authorities, and often run out of medication and suffer mental breakdowns. More critically, the resources that are available to activists are extremely limited. Counselors trained in China’s medical system will not necessarily be able to handle the special needs of activists who have suffered political violence and trauma; while it is even more difficult for activists to find and utilize overseas counseling. Their lack of access to mental health care may also be what has lead activists to list it as an important need.

In addition to psychological support, interviewees also said they need mutual support, a deep level of understanding, and an atmosphere of confidentiality within their team; amicability, communication, and partnership among activist groups, across the ideological spectrum; and space and opportunity to interact with the public, in order to break through the continued marginalization and vilification of activist groups.

The interviewees ranked group and partner support above mental health care, on the one hand, because youth activists believe a supportive group environment can buffer the mental pain caused by the worsening situation; and on the other hand, because the mental anguish caused by group discord is even greater than the pressure of the surrounding environment. Several subjects pointed out that the companionship and support of the group could relieve them of the stress and fear that come with encountering risk; while others said that isolation and marginalization was worse than the pain of losing their freedom. There are also many interviewees who had gotten caught in internal conflicts, saying the blow from those disputes was the main reason they had retreated from the group and taken a break from activist activities.

Clearly, the support or lack thereof for the members of a given activist group is often a determining factor in an individual's ability to continue their activism in a hostile environment. As for how to inculcate a supportive environment within the group, Chinese youth activists have only just begun to look for answers.

2. Opportunities for Learning, Skill-Building, and Mentorship

There are three main capacities youth activists would like to improve through study: professional skills, theoretical analysis, and risk mitigation.

While youth activists often have the opportunity for short-term trainings and workshops, the majority would like to have a more systematic course of professional study available to them in order to expand their skillset, for instance, acting, video editing, and team management.

Given the dramatic political changes in China over the past few years, many activists also want to have the tools to discuss political and social theory, in order to better understand the current political environment, formulate actions and policies that are more applicable to China, and make professional plans for the medium and long term. In addition, some interviewees would like to improve their theoretical understanding of class and gender. It is clear that Chinese youth activists have great expectations for their macro-understanding of politics and society.

In terms of risk mitigation, activists not only want better training in encrypted messaging and digital security, but also emphasized their hope to learn how to process and handle political risk, such as what to do during a police interrogation and how to evaluate the risk involved in a particular activity.

“Work supervision” was also placed in an important position. A number of respondents mentioned that, aside from domain training held at irregular intervals, they hope to benefit from the mentoring of experienced, highly capable activists while on the job. Youth activists not only want to improve how they do their work. They also believe mentorship will help to decrease the anxiety and sense of isolation they feel at work.

Since 2015, wave upon wave of political crackdown has spurred more and more youth activists to either actively or passively make the choice to study abroad, allowing them temporary respite from the risks at home while they engage in formalized study of theory, broaden their perspectives, and try to find new ideas and new opportunities for social activism in China. However, the bar for study abroad is set high, as are its financial costs. During the interview sessions, activists who had access to fewer resources admitted that they were waiting for outside sources to provide them with the funds and opportunities to study overseas.

3. Funding and Manpower

In the current political environment, the funding and staffing problems faced by activist groups are even more serious than during more open periods. These needs are directly linked to the field’s ability to support activists and provide them with educational resources. As described in Part V of this report, activist groups lack the funds and manpower they require to continue and to grow.

VII. Conclusion

Since 2013, the relentless constricting of the political environment has either directly or indirectly created a number of predicaments and vulnerabilities for the Chinese youth activist community. The most notable of these developments is the direct harm caused by political suppression, such as harassment, forced relocation, restrictions on personal freedom, and closure of organizations. At the same time, political austerity has severely restricted the resources available to civil society groups, slowing their long-term growth and leaving them unable to provide adequate support for young people. This in turn makes it difficult for youth activists to achieve economic security and receive family support. The vulnerability of youth activists is significant; under the tense atmosphere and limitation of their personal development, their mental health has continued to deteriorate. At the same time, we cannot deny that activist groups are no “utopias” of camaraderie and equality. Unresolvable conflicts, and unequal distribution of power and resources often lead activists to lose hope in the movement. Fragmentation and attrition are unavoidable issues.

The rise of political risk, the worsening environment for public discourse, the escalation of government controls, the splintering of activist groups, and a whole host of other negative factors have lead youth activists to reach consensus on the “low tide of the movement.” Still, most have not yet abandoned their hope to improve society. Faced with challenges from all angles, they are finding time for self-care, to return to school, to quietly continue their work, or to rethink activist culture and try new ways forward. At the same time, youth activists’ approval of state power has sank. Dissatisfaction with policies and social problems has lead them to question the regime itself. Their attitudes toward activism and politics have become more radical, while in practice they are hibernating and waiting. In line with international trends, youth activists have started to have more complex views of democracy and do not consider it to be a “panacea,” but still have some faith in democratic society and the democratic system, and consider democracy to be essential to social progress.

Even as their situation continues to worsen, youth activist do not intend to stop here. They are even more aware of their need to learn more and to acquire more skills, and they hope to improve conditions within and outside of their social circles, and to give each other more support. However, the shortage of funds and manpower creates a bottleneck for the long-term development of activist groups. The winter of China's social movements will not pass anytime soon. To survive, youth activists will need the support of the world and their own perseverance.

_________________________

[1] “Beijing Yirenping Center to Lodge Complaint Against Police for Raid” (北 京 益 仁 平 中 心 将 对 警 方 查 抄 提 起 投 诉 控 告), Radio Free Asia, March 27, 2015 (https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/renquanfazhi/yl-03272015123943.html); “Yirenping Responds to Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Accusation of ‘Suspected Illegal Activity’” (益 仁 平 回 应 中 国 外 交 部“涉 嫌 违 法”指 控), BBC, April 15, 2015 (https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/china/2015/04/150415_beijing_yirenping); “Five Chinese Feminists ‘All Released’ from Detention” (中国 5 名被拘女权人士“已经全部获释”), BBC, April 13, 2015 (https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/china/2015/04/150413_three_women_activista_release); Beijing Yirenping Center: Statement on Criminal Detention of Charity Workers Guo Bin and Yang Zhanqing, and on the Recent Spate of Crackdowns on Grassroots Social Service Organizations (北京益仁平中心:就公益人士郭彬、杨占青遭刑留及近来当局对民间公益事业密集打压的声明), Weiquanwang, June 15, 2015 (http://wqw2010.blogspot.com/2015/06/2015-6-12-6-12-6-15-2007-2015-4-4-30.html ); 709 Mass Detention of Chinese Rights Defense Lawyers (中 国 709 维 权 律 师 大 抓 捕 事 件), Wikipedia (https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/中國709維權律師大抓捕事件), last accessed May 7, 2019; Series of Crackdowns on Guangdong Labor Rights NGOs; At Least 3 People Criminally Detained (广东劳工 NGO 遭连串打压,至少 3 人被刑拘), The Initium, December 5, 2015 (https://theinitium.com/article/20151205-mainland-guangdong-worker-ngo).

[2] Here “moderate” and “radical” refer to the definitions of these terms used in the common parlance of the Chinese NGO and civil society community. “Radical” denotes ideals that lean toward democratic values and tactics of a public nature, while “moderate” refers to less politicized ideals and low-key efforts made in cooperation with the government.

[3] Someone who the government claims has committed a crime on account of certain political activities or political factors. In China, activities which involve demanding rights or systemic change are often considered to be politically sensitive. In serious cases, those who engaged in such activities may face criminal accusations.

[4] The research team asked the interviewees to rank their needs by importance. 34 valid responses were collected from the 36 research subjects. They were asked to assign a point value to six types of needs: funding, team and partner support, educational resources, mental health support, risk mitigation, and guidance at work. The interviewee would give 6 points to the need they thought was the most important, 5 points to the second-most, and so on. If they thought an option had no importance, they would give it 0 points. Options that a respondent considered to be equal in importance would each receive the average of the remaining points. For example, if a respondent thought that team support was the most important and that all other needs were equal to each other in importance, then [they would give 6 points to team support], leaving 15 points to distribute evenly among the other options. The remaining 5 options would therefore each be given 3 points. The total points assigned to each option across all 34 valid responses were as follows: team support, 157; educational resources, 123.5; mental health, 120.5; work guidance, 103.5; funding, 102.5; risk mitigation, 78.

China Youth Activists Development Concern Group

中国青年行动者发展关注组

chinayouth@protonmail.com

* Based on respect for intellectual property rights and the retention of author signatures, this report is freely available to the public/group/organization for reprinting, printing and distribution, and any form of research/discussion.