Learn how to create space in fiction from this extraordinary literary master

Fyodor Dostoevsky was born on Double Eleven before 199.

01 Dostoevsky's artistic style is unique, and its space is also different from the way of creation of other authors

In this article, I try to analyze the space created in Dostoevsky's novels. "Idiot" and "Crime and Punishment" will be the main material.

Compared with Tolstoy and Turgenev in the "Big Three", Dostoyevsky's writing is neither neat nor dignified, using Tolstoy's writing after reading "The Brothers Karamazov" in his later years. In the diary, it was "unclean and totally unnatural". But this perverse, convulsive, hysterical style gives the novel a black hole-like appeal. This violent and brutal writing achieves a sense of power that other authors can hardly achieve, allowing the reader to be mobilized and fully engaged and involved in the world he has created.

The treatment of space is an inescapable part of discussing Tuo's literary achievements. I have attempted to analyze this remarkable spatial creation, to distill some inspirations, both as a devoted, ongoing reader, and as a creator of architecture, urban design, and other fictional forms. I believe that whether it is architectural design, literary creation, movie scene layout or game scene design, you can draw a lot of nutrients from it.

We mentioned the value of "space" in fictional works in the previous dialogue activity "Space of Literature, Literature of Space (click to jump)" by the Dune Institute. In a more traditional definition, space in a literary work "is the scene, situation, and background in which characters move and move in a story." But in Tuo's analysis, this definition will be challenged.

02 Petersburg as a symbol of "life"

From a macro scale, it can be said that the world in Tuo’s writings is the city of Petersburg; the Russian capital at that time was the place and important background for almost all of Tuo’s stories. These fictional works are set up in real fields, and the streets, bridges, and squares in the novels have their counterparts that do exist in real cities.

However, reading Tuo's works will soon lead to the feeling that the city, the basic space in which this story takes place, is not an inorganic stage background, it seems to be like a certain character, with exuberant vitality and emotional expression. . Belaf also pointed out in "On Dostoevsky's <Crime and Punishment>", "... The degree determines a person's behavior." The saying in the Chinese world "All Jingyu is a love language" is also applicable, although it is inevitably a bit simplified.

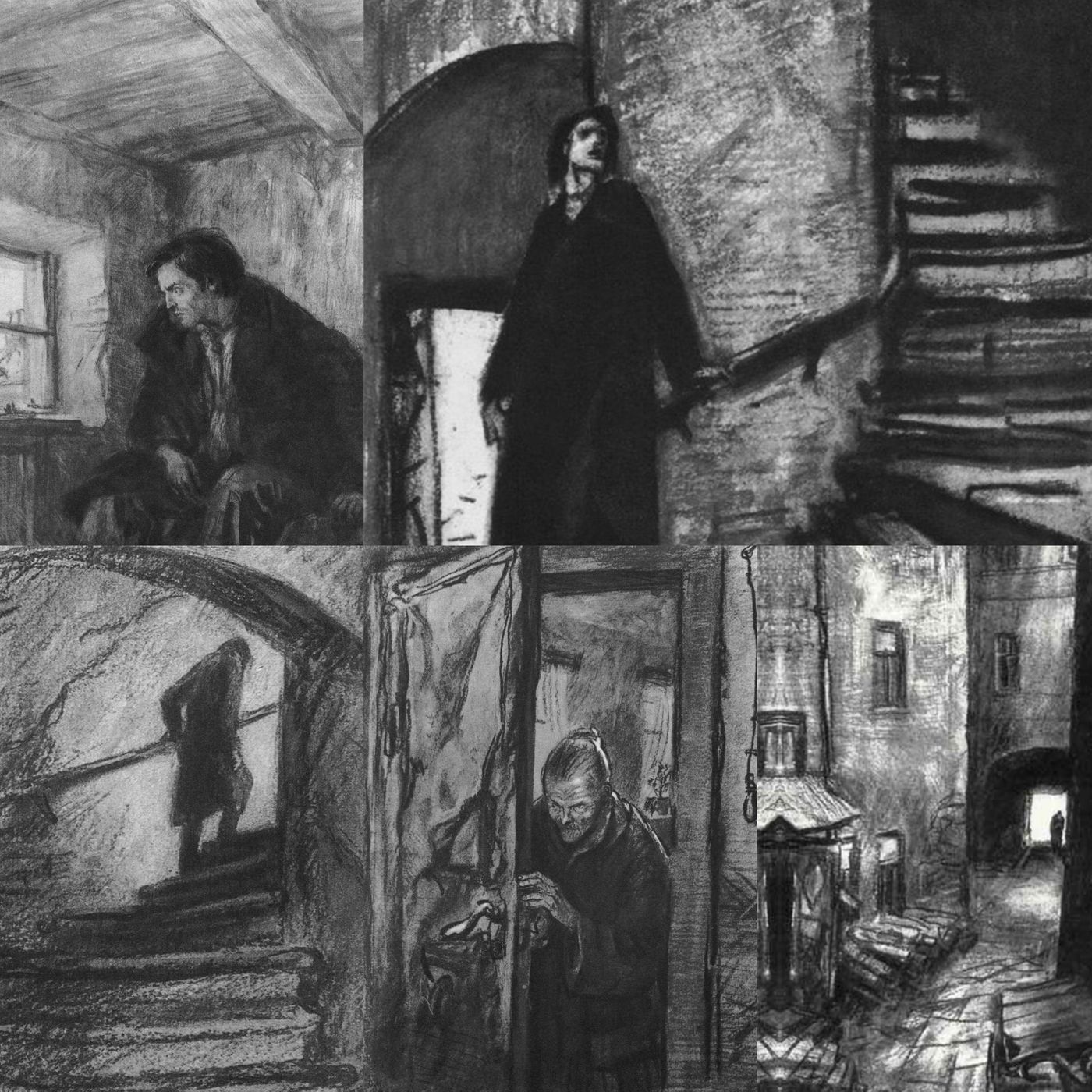

Toshi's Petersburg is not static, not just a foil for the characters at the back of the stage. The city merges with characters, emotions and tragic passions as a whole and moves with the camera. In his fictional world, the city itself represents the mundane world, the cobweb-like system of human relationships, and the messy "life". Apparently, the word "life" here is not sunny and light, it foreshadows a sinking trend - in this city there seems to be a morbid force constantly exerting its influence on the characters, impelling them Show your ugly side. In Crime and Punishment, Petersburg is hot, dirty, and noisy, with bricks and scaffolding haphazardly stacked along the streets, and the sidewalks filled with dust and stench. The spires of streets, buildings, squares, bridges, and churches no longer have a stable relative position and coordinates. They seem to be tightly grasped by an invisible hand, and they have lost their shape when played, leaving only vague positional relationships and A certain poetic impression and silhouette. At this time, the urban space in the real world looks like a labyrinth in the dream of a deranged person. The characters in Crime and Punishment are here to conspire, drink, prostitute, blaspheme, suspect and hurt each other, and keep getting lost in it.

We can say that Tuo's Petersburg symbolizes an unfortunate gravitational field, where the characters fall fatally to the "evil" side of the scale, and ultimately slide toward the catastrophe and destruction of life.

We can also note that there is the end of Crime and Punishment, when the protagonist Raskolnikov is put on trial and subsequently exiled to Siberia , an area that is only briefly described and the long one that precedes it set in cities in great contrast. This desolate and remote place in the north of Russia is far away from the city that is crowded with sinners and overlaps with nightmarish moods, so it can be said that it is no longer subject to the "gravity" of that dark side. As a result, Siberia has acquired a very different extended meaning - here, the sinking life can rise up, the repressed lungs can breathe, and the filthy soul can finally be cleaned up. It is here by a cold and vast river that pulls Skolnikov fell to his knees and was spiritually reborn, as well as Tuo's label-style "salvation of suffering".

Petersburg in Tuo's universe is certainly not without any bright spots. In "Crime and Punishment", the magnificent Neva River and the splendid church roof are some good scenery to cleanse the soul. But just as Belaf thought, the city in Tuo's works is not an external landscape, but the "inner landscape of the human mind", and these bright moments in Petersburg also serve the emotional fluctuations of the characters. Raskolnikov, whose name means "split" in Russian, is constantly divided and polarized in his good and evil, reason and emotion, his attempts to transcend morality and his intuition to recognize morality. The city of Petersburg is also moving synchronously with his contradictory inner world, so the light and the dark are repeatedly projected on the protagonist's eyeballs, and also on the readers' eyeballs.

If we indent our gaze from the scale of the city to the scale of the building, the rented house where Raskolnikov lives, the cramped dorm is like a coffin of despair, the one outside the house of the old woman in the murder scene. The stairwell was like an abyss, and Sonya's three-window room seemed to mean a kind of release and liberation of the soul.

In "Idiot", which was published after "Crime and Punishment", Petersburg is also a quagmire that makes people sink into it, sometimes even with the shadow of hell. Also from the architectural scale, this feature is vividly expressed in the residence of Garnia - this is the place where the protagonist Duke Meshkin rests after arriving in Petersburg. When the protagonist had just settled in his small room, one after another, like crazy and drunk, stuck his head out from behind his door, pushed open the door, came uninvited, and said some abrupt, absurd, and out-of-the-ordinary things to the Duke. In George Steiner's words, the house was like a "Tower of Babel", with a large number of low-income people "gushing out of the damp room like infested bats".

03 Set up somewhere "elsewhere" to form a strong contrast with the main space

If there is a sinful human world, there should be a sinless world outside the world; these two sets of spaces are contrasted with each other, and the characteristics of each other can be clearly displayed. In "Crime and Punishment", we can see that the place where the soul is finally released is far away Siberia , and in "Idiot" there is also this innocent world; Elsewhere" is the equally cold northern country of Switzerland . At the beginning of "Idiot", Duke "Idiot" Meshkin travels from Switzerland to Petersburg (and adjacent Pavlovsk), and at the end he leaves Petersburg again and returns to Switzerland. The two spaces are formed in a contrasting relationship, one as pollution and one as healing.

In the United States in 1961, Robert Heinlein's sci-fi novel "Stranger in a Foreign Land" was published. The premise of its story is that humans send an expedition to Mars. Unfortunately, they all died, but they left an orphan on Mars who was raised by Martians. When the protagonist was 25 years old, he was brought back to Earth by the second expedition. In appearance, he is no different from a normal human young man, but his behavior and understanding of the world are "Mars". He gradually came into contact with the culture and conventions of the human world, and these intriguing and intricate political relationships made him extremely confused and surprised. Of course, at the same time, this "strange guest" in a "foreign land" also reflects many problems and diseases that have long been taken for granted in the human world like a mirror.

It may be said that Duke Meshkin, the "Holy Fool" in "Idiot", is also like a foreign visitor: Duke Meshkin lost his parents since childhood and was raised by Pavliszev. He was sent to Switzerland for treatment for mental illness and epilepsy. Years later, the 26-year-old duke took the train back to Petersburg, a city that was actually unfamiliar to him. But his straight-line attitude of absolute sincerity, kindness, and forgiveness penetrates deeply into the tangled webs of other characters.

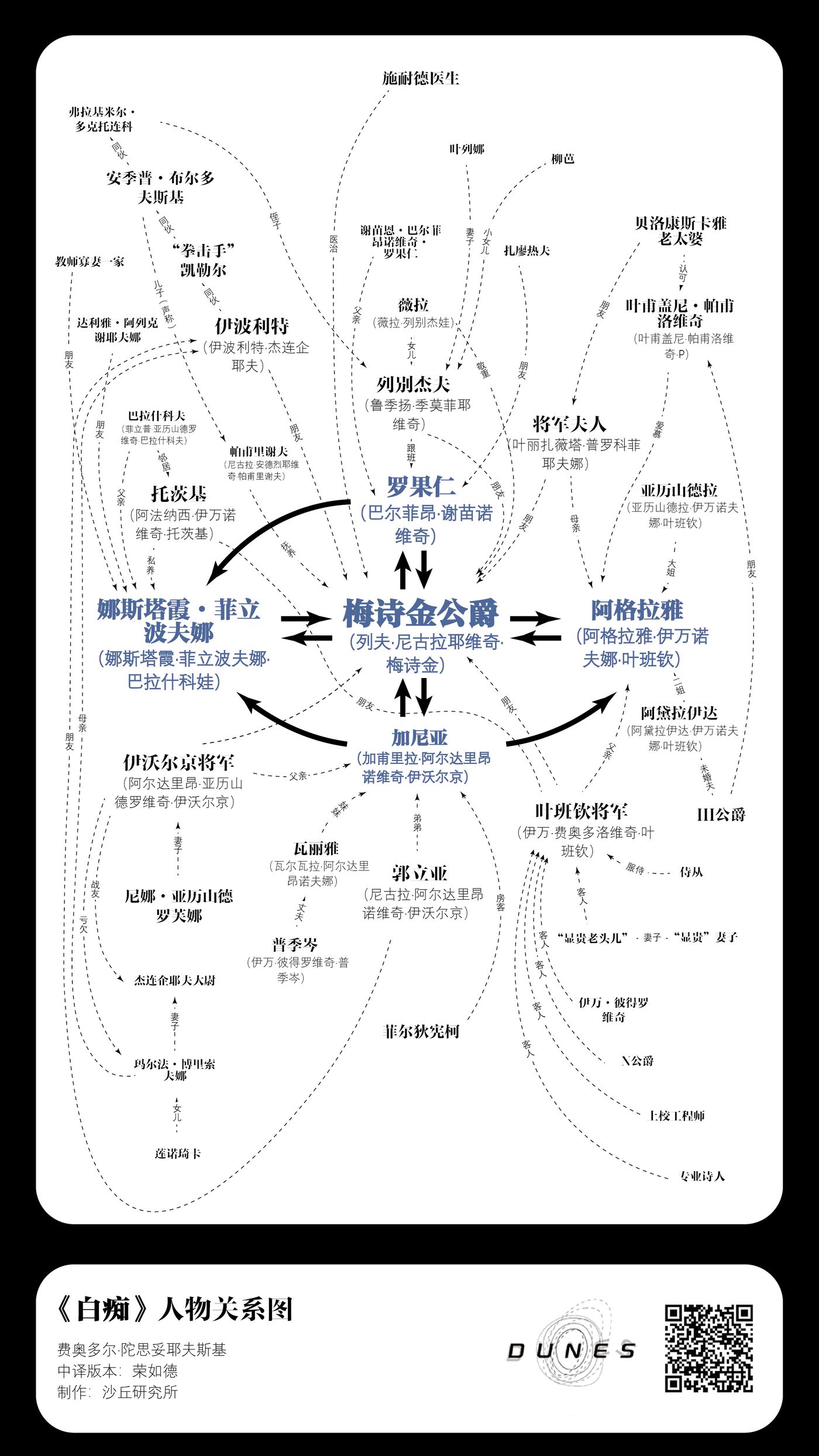

In this character relationship diagram, we can see that the protagonist, Duke Meshkin, is the pivot point where all the storylines rotate and grow, but beyond his "circle", there are many hidden relationships. The space formed by the relationship between the characters is like a picture of a stone thrown into a pond and waves of ripples. Duke Meshkin has no shrewdness, no scheming, and no thoughts to hide from others. Here, we cannot ignore Tuo's strong religious references in the writing of "The Idiot" - he directly called Meishijin " the Duke of Christ " on the manuscript, and when the "villain" Luo Guoren saw the "villain" adding When he was in Niah, he shouted directly: "Ah! You are here, this Judas!"

In Duke Meshkin, what Tuo wants to create is a "completely beautiful person", a "perfect person". The protagonist has infinite love, compassion, forgiveness, and salvation for everyone and everyone. In the opening part, Duke Meshkin said to the mother and daughter of the general's family:

"I left a lot there (Switzerland), just too much. It all came to nothing. I sat on the train (back to Petersburg) and thought: ' Now I'm going to go among people; maybe I don't know anything, but a new life begins.' I am determined to do my business honestly and firmly. I may feel tedious and embarrassed with people. First of all, I am determined to be polite to all people, Be candid..."

- Dostoevsky, The Idiot, Part 1

But it is almost certain and already written that such a one-sided rescue will ultimately end in failure and destruction. In addition to the biblical story, another prototype of the Duke of Meshkin is Cervantes' Don Quixote . The "poor knight" charged with his sword even if he was facing a windmill. When the good, the ideal, the people and emotions worth saving all die at the end of the story, Duke Meshkin finally loses his mind, becomes a real idiot, and is sent to Switzerland again. Spatially, Petersburg, where he came and finally left, represented a turbid world.

04 On the scale of architecture or interior, space is arranged as a stage

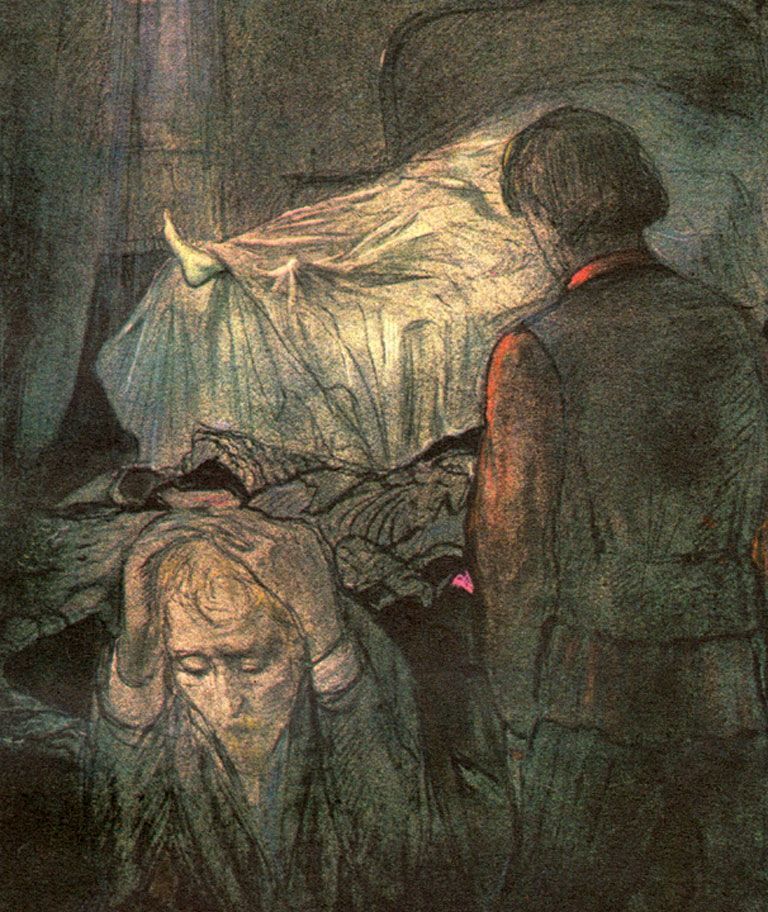

When we cut into indoor places from a macroscopic analysis, we can see that at this scale, the space in Tuo’s work has a peculiar, even bizarre, unreal texture. It is not a clear and definable building, but more like a The stage where the drama takes place. In this sense, what Tuo does in his fictional world is not "architectural design", but the stage design.

Bakhtin, Steiner and Tuo's contemporaries all emphasized the strong dramatic conflict in Tuo's novels. Tuo believes that "theatrical approach is most suitable for expressing the reality of the human condition." The dramatic approach relies on his unique "dynamism", which requires a masterful arrangement of space and time.

Relatively speaking, Tolstoy's novels are visual. He gives us a bird's-eye view, and then passes the big and small characters in turn, and we can see the heroism between their eyebrows and the shiny boots; Dan Tuo's The novel is sound , and we hear their fate and temperament from the long monologues of the characters rolling in excitement. So when we say that Tuo's writing has a strong dramatic feature, it is not only because of the tension inherent in the setting of the novel and the extremeness of the characters (every wicked villain has the appearance of a hero and a giant in some aspects, but on the contrary The hesitant mediocrity is the most pathetic and hateful), but in terms of the operation of the work, Tuo's novels are the same as the dramas in the performances. Only with the help of the voices of the characters - dialogues and monologues - the plot can be obtained. Substantial advancement . As soon as the characters open their mouths, their voices can be several or even dozens of pages long, as if their emotions have been strongly suppressed, and then, like a speaker, they throw themselves absolutely, transparently, and unabashedly in the audience. before. In addition to these "character voices", other plots, that is, the "author's voice" part, are more like description, fast-forward or foreshadowing, and in the end, this part must give way or serve the next The moment a conversation takes place.

The sparkling ensemble shows Tuo's staggering writing ability and energy. In the key scenes of the conflict in "Idiot", nearly 20 people fill a room for a long time, and each character has an ink, - it may be a sentence, a look, a smile or an action -, each The characters are presented three-dimensionally in front of the reader, expressing diverse, rich and changing emotions.

Tuo's lens and what the space he created hides, the two complement each other. Tolstoy provided us with bird's-eye views and panoramas in his works, Turgenev observed the natural scenery from a "quiet and beautiful studio", and writers such as Hugo and Dumas provided us with It provides axonometric maps and HNA maps as clear spatial relationships, but in Tuo's case, these lenses are not available at all. With him, we have no God perspective. Merezhkovsky put it this way:

Dostoevsky is kinder, closer to us. He lives among us, in our melancholy, indifferent city... a man who has just come from life, just now suffering and crying.

——De S. Merezhkovsky, "On Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment" translated by Feng Zengyi

We can probably imagine that in the dark corridors and rental houses, Tuo quietly followed behind the characters, or stood aside in the room of the group show, shooting with a shaking lens (the above is a microphone for sound-receiving) and records. In the lens of this person's perspective, the characters are more stalwart and humbler.

"Idiot" is divided into one, two, three, four plus a short epilogue. Perhaps because of debt avoidance and traveling abroad, the about 400 pages in the middle are loosely written, and some branches seem to be lacking in pruning. But the 200 pages of the first part and the 100 pages of the second half of the fourth part are written naturally. Especially in the first part, time is like being put into a pressure cooker, and the two hundred pages chronicle the less than 23 hours after Duke Meshkin came to Petersburg (within a day and a night--perfect, so to speak). Interpretation of Aristotle's play "Three Uniforms" in Poetics).

In this part, the space always seems to be in a state of being stuffed, and each small room of the finite element is filled with the body of the characters and the abundant motivation and emotion of the characters. In this kind of writing, the density of information is extremely high, and the pressure driven by the plot is extremely high—from the chat of three people on the train, to the first acquaintance and dinner of seven or eight members of Ye Banqin’s family, to the farce of more than ten members of Ganya’s family , and finally everyone gathered, in the "last big play" at Nastasya Filipovna's birthday banquet, the narrative potential was not released in these 150,000 words, until the famous literary history "" One hundred thousand rubles" was staged.

In these group plays, the inking of the room is not very much. It is the moving bodies of the characters and some briefly mentioned layouts that make the space three-dimensional. When we understand that the "spatiality" of the room is constructed by the human body , it seems easier to understand the reason why the characters appear and disappear almost randomly in the middle chapter of "The Idiot". In Pavlovsk, there is a dizzying narrative sequence: Duke Meshkin argues to Aglaya at the villa of General Yebanchin that "I have not proposed to you", to a group of people walking past the green The bench went to the concert. At the concert, they met Nastasya Filipovna and a group of clown-like followers who came to "make trouble." Talk to Aglaya, talk to General Yebanchin, then wander aimlessly at the Duke, meet Keiler, meet Luo Guoren, and finally go to Lebedev’s villa, where a group of people gathered here almost inexplicably, Celebrate Duke Meshkin's birthday until dawn breaks when Hippolyte's forty-page monologue ends.

In this narration from dusk, night to dawn, the time fluctuates fast and slow, the rhythm is sometimes very slow, and sometimes it is suddenly rushed, and the whereabouts of the protagonist and supporting roles are erratic. Besides, everyone seems to have no idea at all. There's also the matter of sleeping. If we understand Tuo's writing from the perspective of a "playwright", we may be able to understand this strange plot advancement a little - a group play, the space of which must be composed of bodies and voices, and a play full of His emotions must be supported by the presence of a number of characters, this is his "chorus". So they have to be on this stage whenever they need it, whether it's a nightly concert, or an early morning villa living room, whether the supporting role was in Petersburg before, or it hasn't been mentioned for hundreds of pages pass. Just like a domineering stage set designer, actors must be present for the key scenes he needs, because they are the pillars and beams of his space.

05 Behind the visible space, fatal tragedy is the driving force of the story

It has to be mentioned that these dispatches for conflict finally serve a classical tragic ending. These stories seem to have been first written in a mysterious destiny, and the ending is already dimly revealed when the beginning appears, and in between these two points, the narrative is compressed, at a rate of elapse that is unreal, The hallucinatory texture is pushed towards the ending, and the characters and emotions are stretched out in the limited space covered by the clouds and mountains.

From this structure, the world of reason and logic only governs a thin layer above the glacier, and what really dominates the movement of the glacier is the huge irrational part of the underwater, which is the mysterious will and the fate in the dark . In Crime and Punishment, we already mentioned that Petersburg was like a dizzying vortex that pushed Raskolnikov to the guilty side. At this time , the characters do not seem to be their own masters, but only a tool used by a certain destiny to express themselves.

In the tavern, he heard the words of the old woman at the side table talking about loan sharks, the idea of murder being read through the mouths of others, like a hint of fate; in Hay Square, he heard by chance the time when the old woman's housemate would be Duan was not in the house, which was the perfect time for him to do it, and it seemed like an invisible force was helping his decision to murder; finally, on the day of his action, the axe he was going to take was not in its place, when he was close to When he gave up, "something suddenly lit up" in the housekeeper's hut, and when he got closer, he saw that it was actually an axe. In Zeng Siyi's translation, Raskolnikov smiled and thought:

Reason is useless, the devil shows his powers!

In Tuo's fictional world, there are often demons. In The Idiot, this coincidence of space and events is also deeply embedded in the text, decisively affecting the direction of the story. On the train bound for Petersburg at the beginning, it was right that the Duke Meshkin and Luo Guoren, who had a long love-hate entanglement, were sitting opposite each other. Rong Rude's translation reads: "If they knew what was so special about each other at this moment, they would have been amazed by the odd chance that they had sat opposite each other in the third-class compartment of the Petersburg-Warsaw train."

The other end of this complicated love-hate relationship, Nastasya Filipovna, also met the Duke in this "destined" gesture. If we compare "Idiot" with "A Dream of Red Mansions" at this point, it may not be as far-fetched as it seems. At Ganya's house, when the duke saw Nastasya Filipovna herself, he murmured to her:

"...Because that's what I think of you.... I think I've seen you somewhere ?"

"Where? Where?"

"I seem to have seen these eyes of yours somewhere...but it's impossible! It's just my hallucination...I've never been here. Maybe, in a dream..."

06 Conclusion

I did not "decipher" the way of writing on Tuo's space, and such a claim would be foolish. Suffice it to say, at some angles, I tried to capture the character of these spaces. Tuo's space is not a static set, it is a role.

On the urban scale, Petersburg and a certain "elsewhere" can form a contrasting relationship, carrying symbolic meanings, laying the basics of good and evil judgments, as well as the basic materials of tone and atmosphere for the story. On the architectural scale, rooms and scenery are internalized "image scenery", which can change and move with the movement of the camera and the characters.

On the other hand, those FE interior rooms deserve our attention in particular because they are, or are about to be, the revolving stage when the group play "starts" - the monologues of the characters, the body movements, the table in the room, the wine glasses, The fire can form an organic group dance together. At this time, the space and people must need each other. In these places designated by Tuo, the characters "sing on the stage", and in turn, the characters' bodies and voices in turn support the space. form. Finally, if we want to really go deep into Tuo's role relationship and space placement intention, something called "accident" or "fate" governs these arrangements in depth, or, in other words, these "devils" and " fortunes" "It is fundamentally the larger and more prior premise that the novel is prior to space and time. These mystical shades polish the shape of the characters and spaces—if it could have ended more selfishly, that's what fascinates me most about Tuo's work.

references:

Leo Tolstoy, translated by Ren Jun, "The Last Days of Tolstoy", Tianjin People's Publishing House, 2020, see chapters "October 12" and "October 18";

[1] Fei Dostoevsky, translated by Rong Rude, "Idiot", Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 2015;

[2] Fei Dostoevsky, translated by Zeng Siyi, Crime and Punishment, Zhejiang Literature and Art Publishing House, 2019;

[3] Fyodor Dostoevsky, translated by Rong Rude, The Brothers Karamazov, Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 2015;

[4] George Steiner, translated by Yan Zhongzhi, Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, Zhejiang University Press, 2011;

[5] De Sze Merezhkovsky, translated by Yang Deyu, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (Top and Bottom), Huaxia Publishing House, 2009;

[6] De S. Merezhkovsky, translated by Feng Zengyi, Cao Guowei, "On Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment", "Russian Review" Vol. 2 Vol. 3, 1890 ;

[7] John Middleton Murray, "Crime and Punishment" translated by Dai Dahong, "Fyodor Dostoevsky: A Critical Study", London: Martin Secker, 1923;

[8] Lei Peter Grossman, translated by Mi Xuyang, "The City and the People of "Crime and Punishment", Moscow: State Literary Publishing House, 1935;

[9] Joseph Frank, translated by Dai Dahong, "The World of Raskolnikov", "Wenhui" magazine, pp. 30-35, 1966;

[10] Mi Xuyang, "The Poetics of Names in "Crime and Punishment", Beijing Youth Daily, 2016;

[11] Bakhtin, translated by Bai Chunren and Gu Yaling, Problems in Dostoevsky's Poetics: Theory of Polyphonic Novels, Sanlian Publishing House, 1988;

[12] Fei Dostoevsky, translated by Feng Zengyi and Xu Zhenya, "Man Does Not Live by Bread: Selected Letters of Dostoevsky" Shanghai Translation Publishing House, 2013;

[13] He Yunbo, "Dostoevsky and the Spirit of Russian Culture", Hunan Education Press, 1997;

[14] Fan Jinxin, "Time and Space in Dostoevsky's Art", "Peking University Journal - Foreign Literature", 1983

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!

- Author

- More