'Enemy of the state' elected president: a sea change in Colombia's political landscape

On June 19, Gustavo Francisco Petro Urrego won the Colombian presidential election with 50.51% of the vote. Before being elected president, Petro was a Colombian senator, former mayor of Bogotá, a socialist, and a partisan of the Movimiento 19 de Abril. He defeated Federico "Fico" Gutiérrez, a representative of the traditional Uribismo, with 40.9 percent of the vote in the first round.

Before that, the left, which was associated with guerrillas and violence, was a dirty word. Rep. Luz Mariana “Luzma” Múnera, the founder of the left-wing party Polo Democrático Alternativo, recalled, “In the past, when we took to the streets to hand out flyers, people would turn towards us. Spit on us and call us "son of a bitch" guerrillas". However, the guerrilla-turned-Petro became Colombia's first left-wing president.

Times have changed.

Full left turn Colombia

In the 19th century, the Colombian Conservative Party (Partido Conservador Colombiano) and the Liberal Party (Partido Liberal Colombiano) were established successively to represent the interests of the rich class, mainly landowners, and the businessmen. The struggle between the two intensified and ended in 54 civil wars. In the early 20th century, violence and murder became the norm in Colombian politics.

On April 9, 1948, a wave of violence swept across Colombia following the riots that followed the assassination of left-wing Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in Bogotá. Although it started out as a popular uprising, the landed elites of the Liberal and Conservative parties participated in the violent conflict to advance their own political and economic interests. Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, commander of the Cali 3rd Brigade, who suppressed the riot, was promoted and in 19512 was promoted to commander-in-chief of the army.

In 1950, the conservative Laureano Gómez Castro came to power and imposed a dictatorship, which was continued by Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez, acting president. this policy. In 1953, Pinilla, with the support of the moderate wing of the Liberal and Conservative parties, staged a military coup that overthrew Gomez's regime. But soon, the duly elected president also began to exercise a dictatorship. In this case, the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party quickly reached a compromise. In 1956, the two parties signed the Benidorm Treaty in Spain, pledging to take turns between the two parties until 1974. In 1957, Pinilla arbitrarily extended the presidency and ordered the arrest of the presidential candidate jointly launched by the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, sparking fierce protests. Under the pressure of the then army commander-in-chief, Pinilla finally stepped down.

Although the Conservatives and Liberals have since shared power, most Colombians are still not represented by either party. Different opposition movements have emerged on the Colombian political scene, and driven by a continuing wave of violence, peasants in southern Colombia have begun to arm themselves to protect themselves. The landlord elite demanded that the government suppress these peasant armed forces. The peasant armed forces eventually became partisans. In the 1980s, large landowners, business leaders, and international drug cartels were also involved, forming various paramilitary groups, which led to the decades-long armed conflict in Colombia.

All parties to an armed conflict inevitably commit war crimes, but it is the Colombian government and paramilitary groups with extensive historical ties to the Colombian government that are responsible for the vast majority of violence against civilians. An official report commissioned by the government found that 70 to 80 percent of the more than 200,000 murders linked to armed conflict were committed by the state and paramilitary groups. Nonetheless, the guerrillas are still blamed for being the makers and initiators of violence, and are mistakenly identified with drug cartels, and the left is stigmatized as a result.

With the peace process in Colombia, though, such animosity has diminished. At the same time, inequality in Colombia has widened since President Álvaro Uribe Vélez took office in 2002. According to statistics, Colombia is the second most unequal country in Latin America after Brazil, and its social mobility rate is the lowest among the 38 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. These reasons have contributed to the rise of left-wing parties in mainstream politics, while protests on the streets of Colombia over the past few years have made Petro's victory possible.

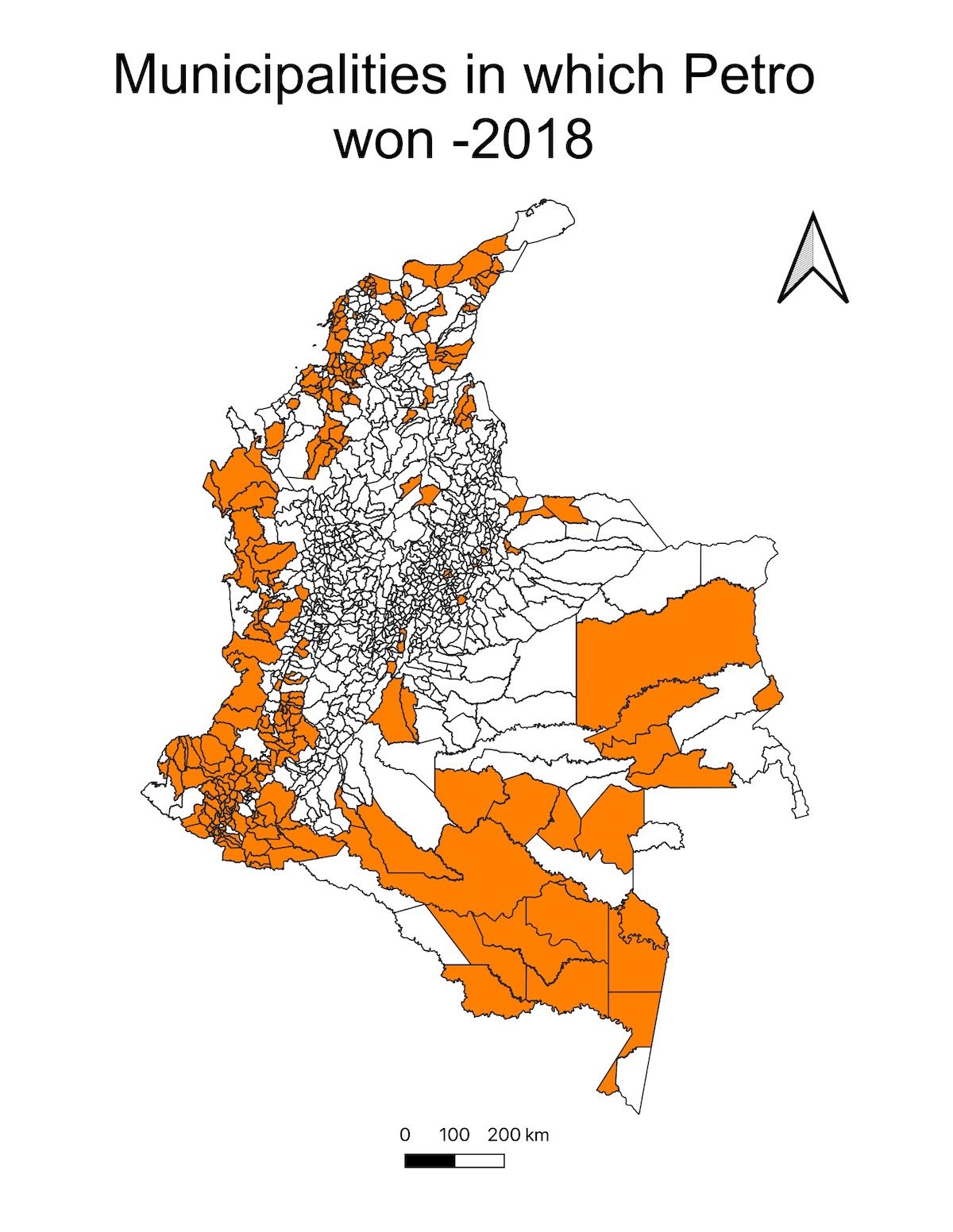

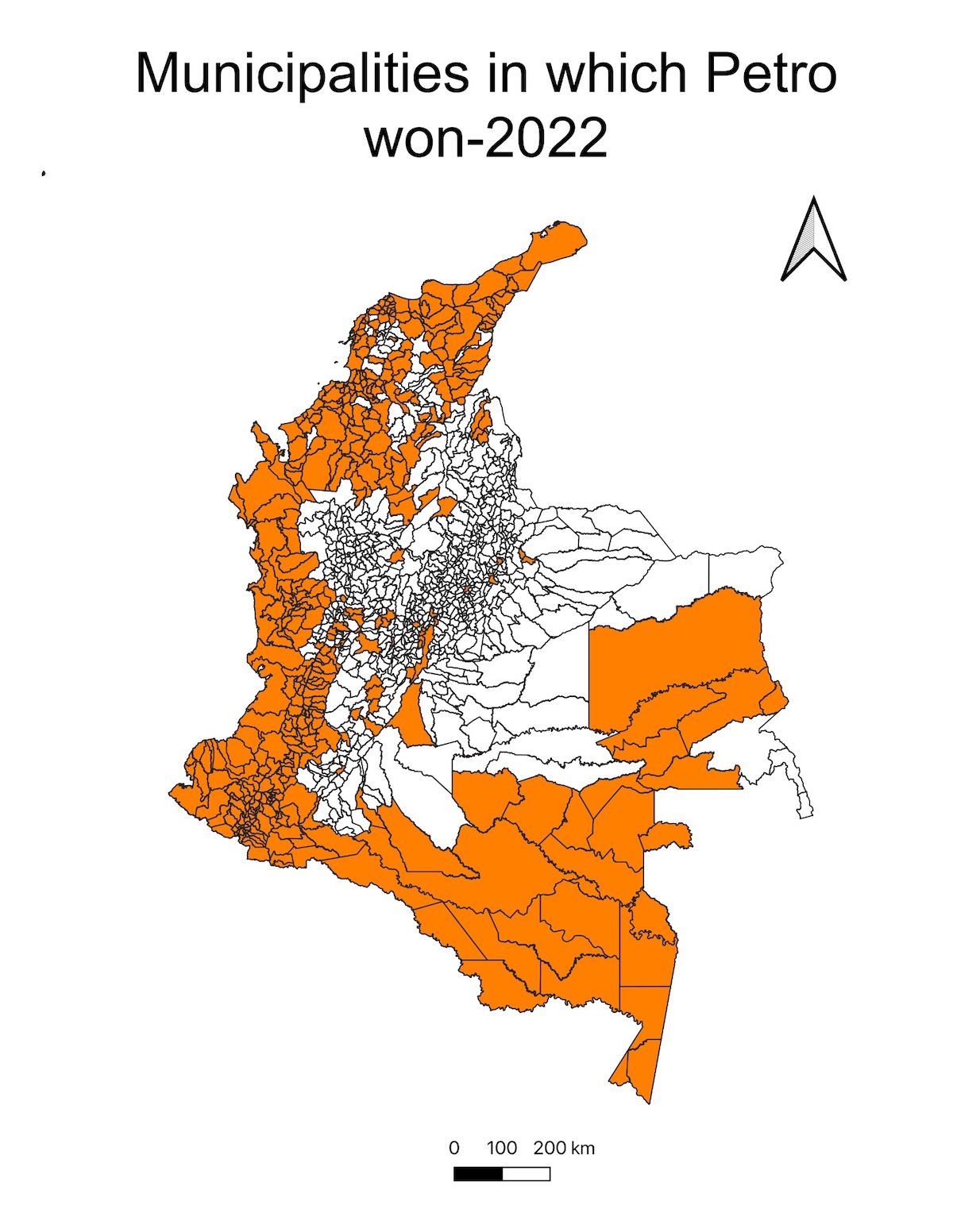

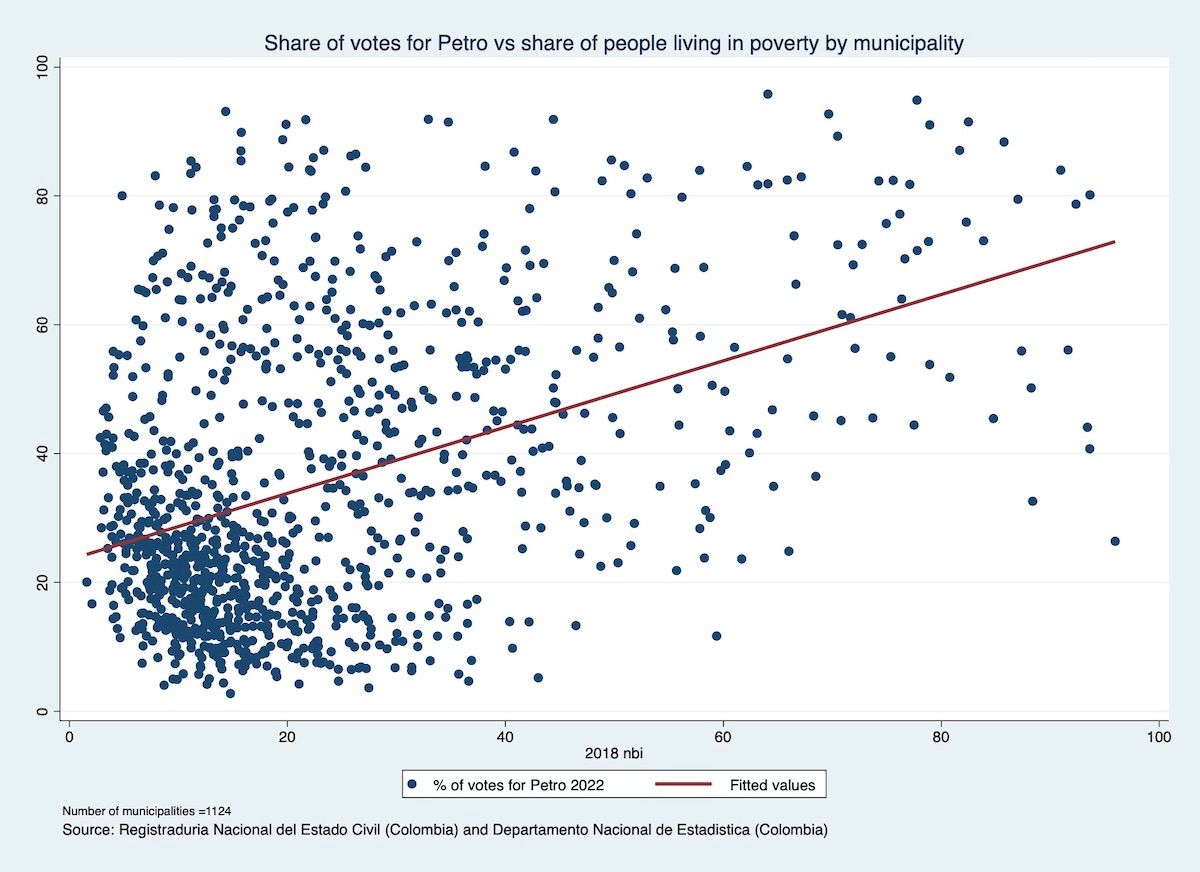

In 2018, Petro also participated in the Colombian presidential election and faced off against the incumbent President Duque (Iván Duque Márquez). At that time, he won 25% of the votes in the first round of voting, and in the first round of voting this year. , he received 40.3% of the vote. He received more votes in 94 percent of Colombian cities than in 2018. According to an analysis by Professor Laura Ortíz of Colombia's Universidad de los Andes, Petro won a landslide victory in Colombia's big cities and fringe rural areas, while , there is a strong correlation between his vote support and the proportion of the poor.

Those who voted for Petro wanted the Colombian government to care more about their demands, which both echoed Petro's political views to end corruption, violence and injustice in Colombia, and that voters are using their votes to rule Colombia for two decades. The Uribe Doctrine says no.

Farewell, Uribe

In 2002, little-known senator Alvaro Uribe was elected president of Colombia under the theme of "security". He promised that when he took office, he would fight guerrillas and the drug trade with tough measures. Of course, it wasn't known at the time that he was in close contact with drug dealers himself. In 2018, cables declassified by the U.S. National Security Archives showed that the U.S. embassy had known in 1993 that the Medellín Cartel, once the largest in Colombia, had funded Uribe’s campaign.

This does not prevent Uribe from maintaining a close cooperative relationship with the United States. Since he took office, the United States has funded Colombia billions of dollars to fight "Marxists" engaged in "drug-trafficking terrorism". This is the most notorious "Uribe Doctrine". On the surface, Uribe Doctrine emphasizes stability, conservatism, and neoliberal concepts such as markets, competition, and entrepreneurship; in fact, it maintains regime stability with a constant state of exception, and uses force to fight drugs. The guise of clearing the way for the expansion of capital.

During Uribe's tenure, all those who questioned him became partisan allies and terrorists, the targets of political persecution. In 2004, Alfredo Correa De Andreis, a prominent Colombian sociologist, was arrested by Colombian security services on entirely fictitious evidence and was admitted shortly after his release. Members of a military group were shot dead. In less than a year since Uribe took office, the Colombian government has carried out 4,362 arbitrary detentions. And from 2002 to 2010, the Colombian army carried out extrajudicial executions of 10,000 civilians.

In 2014, journalist Dawn Marie published Drug War Capitalism, which examines the links between Colombia's drug war and neoliberalization over the past two decades. . Mary noted that the U.S.-funded war on drugs in Colombia has once again legalized paramilitaries as spearheads in the eradication of drugs. However, paramilitary organizations themselves are members or partners of drug cartels. Therefore, their goal is of course not drug cartels, but control of territory and society. The extreme inequality that forces rural areas to work in drug cultivation gives paramilitary groups justification to remove barriers to land development for the multinational corporations they serve. The war on drugs allowed the state to turn a large portion of its population into an enemy, and the resulting fear engulfed society in fear, giving the war on drugs yet another legitimacy.

And thanks to the Uribe Doctrine, Colombia has become America's main ally and spearhead in Latin America. The Uribe government has welcomed U.S. military bases, advisers, troops and guardians into its strategic position to protect what Washington has long considered a backyard.

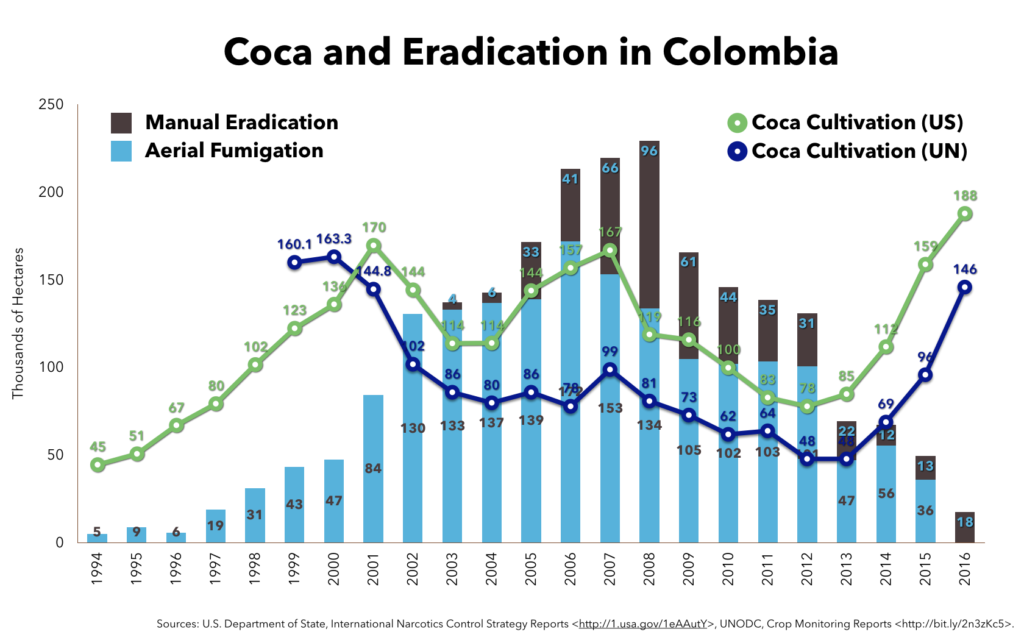

Uribeism, however, has ebbed since the 2016 peace deal was struck. This is both because of the rising inequality described above and because it has been discovered that even more area in Colombia is devoted to the production of coca (the raw material for cocaine) than it was before the war on drugs. And in March 2022 legislative elections, Uribe's Central Democratic Party has gone from the most powerful party in Congress to a minority.

Of course, Uribe is still active in politics, and Petro's coming to power is not a panacea for the country's ills. As president, Petro could face immediate challenges. His relations with the Armed Forces and the U.S. government could deteriorate rapidly, especially if Petro delivers on his promises: to replace the current military high command, rapidly change national security policy; to promote a voluntary alternative, namely coca cultivation A man who plucks illicit crops with state support and turns to other industries to eradicate coca; improves relations with Cuba and Venezuela, or starts a new peace process with the guerrilla National Liberation Army (ELN) will all have a negative impact on his presidency. form a challenge.

Meanwhile, regardless of Petro's progressive agenda, the issues of inequality and insecurity that plagued Duke are likely to resurface. Colombia's main political hurdle -- providing greater security on the country's rural fringes and expanding economic opportunity in impoverished suburbs -- will be his toughest challenge, especially as he hopes to move away from an economy dominated by oil exports. mode to solve this problem. While two decades of neoliberalism have left Colombia's tax base weak, expanding government revenue to support his social-democratic rule will be another challenge.

The road ahead is thorny, but Márquez says the twentieth century begins with Gaitan’s assassination on April 9, 1948, and Yale historian Greg Grandin says June 19, 2022 Maybe a turning point. In any case, from Honduras, Chile, Bolivia to Colombia, the ideal of social democracy in Latin America, through pain, suffering, and overcoming daunting obstacles, will never die.

(Editor in charge: New Bremen)

Like my work? Don't forget to support and clap, let me know that you are with me on the road of creation. Keep this enthusiasm together!