Matters 社區官方帳號 Official account of Matters Community For English community: @Matterslab Everything related to Web3

"Presence" Nonfiction Writing Season 1 Press Conference | Digging and Burying: Personal Life Narrative as a Kind of Nonfiction

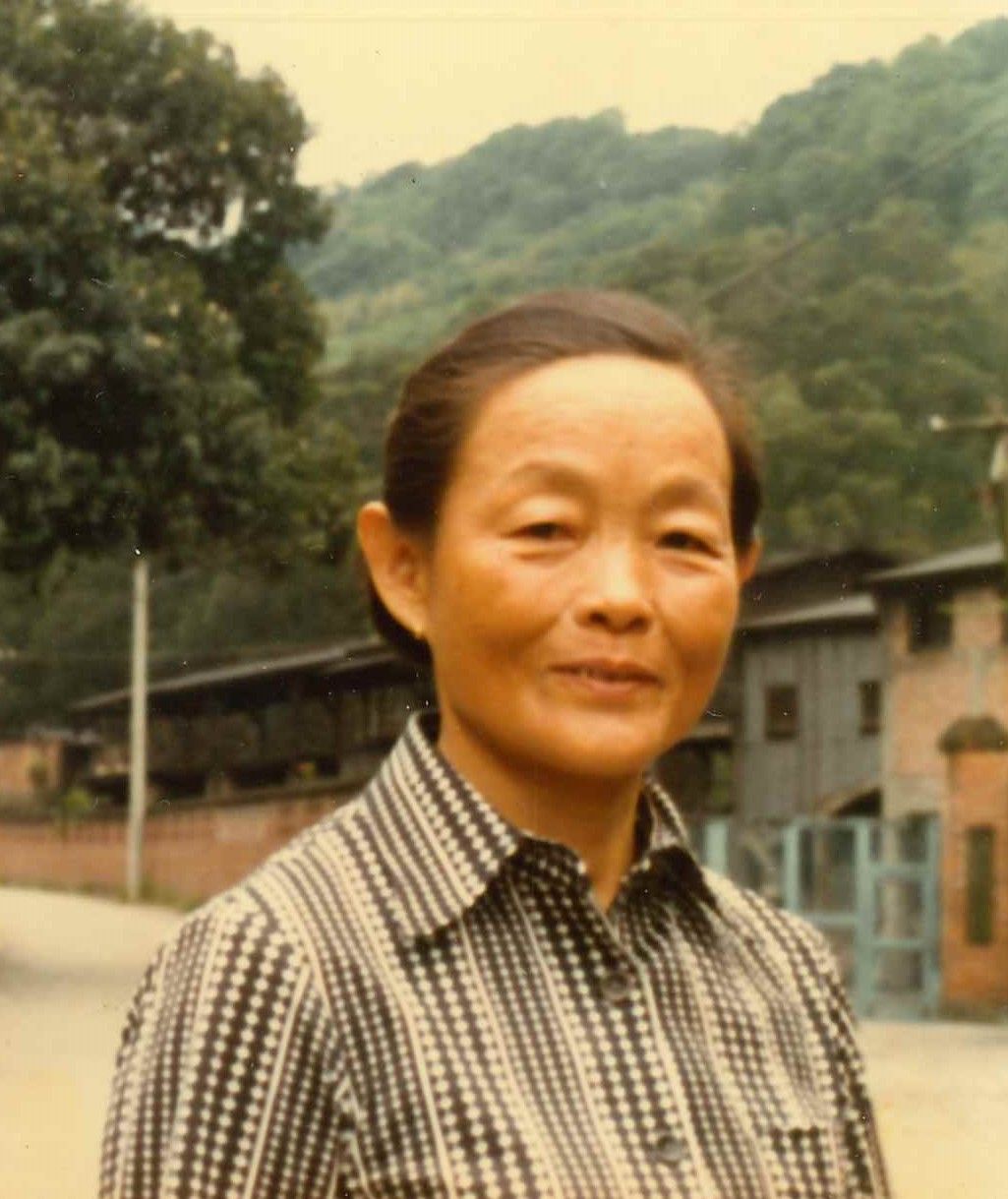

Speaker: Dai Bofen's "Presence" Season 1 Second Prize, author of "The Last Female Miner - Zhang Gui's Life Narrative"

Gu Yuling Writer, Assistant Professor, General Education Center, Taipei University of the Arts

Debbie:

When it comes to miners, most people picture male miners, but I knew from a young age that my grandmother (grandmother, mother's adoptive mother) was a miner and the whole family lived in the mine dormitory. I was born and raised in Taipei. When I was a child, my parents had already left the mine, and my father didn't like our return to my parents' home. My relationship with the mine was very estranged, and my grandmother was like a distant relative. In the past 30 years, I have done sociological research on many different topics, but when I came back to myself, I suddenly found that my life experience and my own were broken, and I was indifferent to such a break. It's someone else's rights, why didn't I see the close grandma?

About ten years ago, I wanted to write about the grandmother who lived in the Haishan mine. This seed was buried for a long time. In the field of sociology, writing is less in the form of self-narrative, and most of it is based on psychology. Now that I am over 500 years old, I am very familiar with academic norms and censorship systems, and I have fulfilled the requirements of the academic world, but what do I want to do? The academics I talk to often don’t understand the ideas I want to express, and they have to entangle with foreign literature and Taiwan’s local experience. After playing this game for a long time, I feel tired of the way of text production in academia and want to seek breakthroughs. . One of the things I want to do most is get to know my grandma.

Before I got the "Present" scholarship and started writing, I had no idea about Mamaw's story, especially the details of life in the mines. For the people at the bottom, their life world is so ordinary that it is not worthy of a big book like the biographies of great men. They rarely tell about their life experiences, let alone painful and unbearable memories.

I haven't done "non-fiction writing" before, and this is even the first time I've heard it. Thanks to the affirmation of the "present" reviewers, I had to complete the first draft in just three months, which is shorter than the normal academic research cycle (including fieldwork, dissertation, etc.). If it weren't for the deadline pressure of being "present", I would probably have kept it in my mind.

sociological imagination

After writing this story, I saw Mamaw's upbringing and her plight. Of course, the predicament was not caused by her, and the personal predicament must be understood within the social structure. C. Wright Mills' The Sociological Imagination helped me understand why Mamaw's life was so hard. As a female researcher, I will also consider from a feminist perspective what kind of experiences a female miner might encounter, and what are the differences in the life experiences and family roles of female miners and male miners. In order to link my grandmother's personal experience with the structural changes in Taiwan's history, I listed my grandmother's life events as a chronology on the one hand, and the historical chronology of Taiwanese society on the other. The historical materials after the Restoration, including Taiwan's political changes, as well as special materials on the history of Taiwan's mining industry.

With reference to the two, we can understand whether the changes in Grandma's life were due to changes in the great times, or because of changes in the family structure?

In the process of interpretation, I have to make some trade-offs: what themes are to be reproduced and in what way? As a sociology scholar, I am used to asking or responding to questions from others. For example, many people will wonder, do women have jobs in the pit? If women can't enter the pit, why? The most popular argument at present is political theory, that is, Jiang Song Meiling once visited the mining village and found that it is very dangerous for husband and wife to work in the pit at the same time. If a disaster occurs, the children in the family will lose their parents at the same time. After combing through the information, I found that Jiang Song Meiling did visit the "Mining Association New Village" in Pingtung, but this was not a mining village, but an air force military dependents' village; instead, Mr. Jiang Jingguo did visit the mining village, and it was Haishan where Mama worked. coal mine. Perhaps this statement is just to present the people-friendly image of politicians.

There is another saying that it is a taboo that women will attract bad luck if they enter the pit, but it is obviously inconsistent with the facts and is anecdotal. The most ridiculous thing is the theory of order, which believes that it is hot in the pit, mixed with men and women, and will cause emotional disputes. The mine tunnel is two or three kilometers deep underground, and the coal lanes are far apart. The miners work in the dark pit and cannot see each other at all. Coupled with the rotation of the work in the coal lane, whoever works next to them often doesn't work. I don't know, why is the relationship between men and women ambiguous?

But why is it considered taboo for women to work in pits, while women miners seem to have disappeared in history? Probably because women are marginal characters in the mines and are not seen. During the Japanese occupation period, the number of female miners was only one-tenth of the total number of miners. The working hours were not stable (4-13 hours), and the wages were far lower than that of male miners (1.3-2.1 times that of female workers in Taiwanese male workers in the pit. Taiwanese male workers outside the pit are 1.1-1.9 times as many as female workers), and most of them also do second-hand work to assist men.

There are frequent mining disasters in Taiwan. After the mine disaster, women lose their husbands and the financial support of their families. How should women deal with themselves at this time? Who will provide for the family, who will raise the children, and what will happen to family relationships? Under the changes of the mine environment, the workplace environment has also undergone great changes. When Taiwan's mining industry faces the depletion of its veins, it needs to continue to dig deeper, and the miners take higher risks, so that three major mining disasters occurred in 1984. It is morally unacceptable for the general public to exchange the life of miners for coal mines. From an economic point of view, the cost of producing coal mines in Taiwan is more than double that of importing coal mines. Variety. First of all, from the perspective of family economy, after the death of her husband, female miners can only get by with debts. In fact, most miners are unable to make ends meet and keep borrowing money from the company, which also leads to being bound by the company; this is also due to the risk of mining work. , Many people don't know whether they can come out alive after going into the mine, so "the present is drunk and the present is drunk", there is a kind of hedonistic atmosphere. Secondly, it will cause children to drop out of school, such as my mother and uncle who dropped out of school because of this. Finally, women may also go out to work underworld as a stopgap measure.

In terms of household labor, some changes have also taken place after the death of my grandfather. The responsibility for raising children and running the house falls on Azu (grandmother's mother-in-law). This mother-in-law has always been regarded as a "kefu" by her neighbors because her two husbands died. After the mine disaster, she vented her grievances on her grandmother, believing that she killed her son. Mammy had to rely on Azu for help and endure the physical and verbal violence she inflicted on her. At the same time, grandma had to endure the bullying of her uncle, and finally took care of her son and mother-in-law.

Through interviews, I learned that Grandma is such a resilient woman; in an environment where she could barely survive, Grandma still went her own way. The mine is an environment where there are more men than women, and women without men’s protection are often harassed by men. Later, in the mine dormitory, Mamaw also met her second man, Jin Fa. In this relationship, in addition to financial support, Mamaw also received family and spiritual support. Although they did not have a formal marriage relationship, they supported and understood each other for a period of time until Jinfa passed away. Without his support, it might be difficult for Mamaw to go on.

Separation is a process that most people must go through in their entire lives, but it is really heavy on Grandma. Grandma lost three sons and two husbands at the same time. Because there were too many dead relatives, she decided to unite all the deceased relatives to worship together on August 15th, turning grief into a fate that can be accepted and responded to in life. . The parting of life and death in the past is now a light cloud for grandma, and I can still feel the pain and torture she experienced at every moment.

In addition to mining, at the end of the Japanese occupation, grandma also participated in the "Taiwan Island Fortification Project" (in 1944, in order to resist the invasion of the US military, construction was being carried out everywhere in Taiwan) to dig air defense trenches. After the war, Yamamoto Mining ended. When grandma left Tainan to marry her, she happened to encounter the "February 28 Incident". She witnessed the Kuomintang troops entering the city and many people were caught and executed by "stone statues". These experiences in her life constitute the testimony of Taiwan's modern history.

Reflexivity in the Field

In sociology, "reflexivity" means that the actor consciously faces the society, understands the meaning of the situation he faces, and responds appropriately. What kind of questions would a modern person who does not know about mining villages and mining at all ask a person who has lived in a mining village all his life? I put myself in an anthropological-like state of infantile ignorance, going into fieldwork where I was constantly reflecting on my relationship with them. This writing also shallowly buried my personal life experience. I did interviews, family genealogy, and selection of events, looking at how events complement and corroborate each other. But I always seem to feel that there are some things that should not be said. For example, I wrote some about how I can make up for the broken identity between generations, but I also deleted it because of hesitation and struggle.

I also tried to answer the dilemma of women in a patriarchal society. For example, the resentment and reconciliation between my mother and her own parents, through interviews or communication between family members, let my mother understand the adoption process and resolve the resentment in her heart, which was unexpected.

In the following chapters, I have already left the life history of my grandmother, and entered into a reflexive criticism of the social level, such as why there are continuous mining disasters in Taiwan, how the miners respond after the mining disaster, and how the country and society respond to the trauma of the mining disaster. In reflexive thinking, I also hide some topics that I don’t want to touch, such as the daily life of a male miner, the role of my father (I only realized my incomprehension towards my father during the writing process), and understanding the limits of self-disclosure .

The last question for reflection is the relationship between man and nature. Should tragic memories be preserved or forgotten? Before seeing the Haishan mine, I intuitively thought that it should be preserved because of its historical significance; but when I found the abandoned site, I realized that nature had taken it back. I also saw that after Mama left the mining village, her life was much happier than before. Should the mine be turned into a tourist attraction, or should it be left to nature? I still haven't found an answer.

"Presence" Discussion: Dai Bofen & Gu Yuling

"Present" host:

Mr. Dai has completely combed Zhang Gui's life history for us, and we seem to have heard a good story. Next, I hope Mr. Gu can respond to Mr. Dai's work, because the writings of the two authors are similar. They both face Shen Zhong's history, pursue memory, understand and explore the oppression of the system, and have expectations for the future.

Gu Yuling:

For me, this lecture is actually a supplementary lesson. When the mining industry in Taiwan ended at the end of the last century, I had just joined the labor movement. I also met miners who were fighting because of pneumoconiosis. I also visited Pingxi, Houtong and other places. Until now, I still have an important case in my hands, the occupational disease case of a MRT worker with diver's disease. In the 1980s and 1990s, with the decline of Taiwan's mining industry, many workers left the mines and entered the construction industry. Because they were familiar with tunnel operations, some people entered the construction site of the Taipei MRT; Got diver's disease again. After listening to Mr. Dai's narration, the whole story is coherent.

With his excellent writing skills, the author intersperses historical events with the stories of the female miners. He not only uses historical materials to create a panoramic view and clearly arranges the historical context, but also has many ingenious connections between chapters and chapters. The whole book is as beautiful as a historical novel. . In just over 40,000 words, we not only saw the history of mining and labor in Taiwan, but also the history of women. During the reading process, we got a lot of information and knowledge. The female perspective runs through the whole text. The author grasps the female narratives such as small foot binding, menstruation, pregnancy, domestic violence, workplace sexual harassment, etc., and meticulously writes four women of different generations-Azu, grandmother, mother, and the author. relationship and tension. The writing is full of emotion, but at the same time quite restrained. This kind of restraint is especially reflected in the author's almost non-judgmental writing about how many choices these women have in their time and space, and how much mainstream society's views on women have been inherited. Although the author is in it and has close observations of these relatives, I think it is very difficult for her to "present without evaluation", which is also the core position of "non-fiction writing".

The first question I want to ask the author is, being in the family field where the relationship is tugging, and knowing the tension between each other very well, but when writing, how to consciously let these women's appearance without evaluation Real appearance? I hope the author can share more.

In addition, I have also observed that the author's writing on Taiwan's mining industry follows two interrelated axes, one is "capital" and the other is "labor". The latter includes historical materials and oral collections of mining environment and labor. The process, especially the details of the gender division of labor; the transfer of capital ownership in the former is closely linked to the change of regime, from the Qing Dynasty, the Japanese colonization, the early post-war period, to the post-mortem. About mine operations. For the first time, I learned about the usual preserved cabbage in bento. It turns out that it is not only because of the meal, but also to replenish the salt lost through sweat. This kind of scene description is very familiar to me. It reminds me that the MRT workers also work in the high temperature of over 40 degrees in the tunnel. When they came out of the pit, the workers described that they took off their rain boots and hung them upside down, and sweat gushed from the rubber shoes like rain. run off. Another example is when writing about the bathhouse, the author used the metaphor of the grandmother who helped the bathhouse to boil water, which is very expressive. On the other hand, De Boffin, as a sociologist, in a limited space, accurately grasps which events to choose to describe capital, so that we can see how to combine the transfer of capital with the political situation. For example, during the First World War, the war brought the international coal demand to a peak, and the Japanese Empire developed coal mines in colonial Taiwan in combination with the needs of Japanese capital. At the end of World War II in 1944, miners were mobilized to dig air defense trenches in Pingtung, which also reflected Japan's "fortified Taiwan" strategy in military expansion. Taiwanese were forced or recruited into the Nanyang battlefield.

After World War II, the Kuomintang took over the mining industry, and then liberalized the business and transferred it to private capital. After entering the 21st century, the mining farms ended, and the urban planning was followed by the problem of land change and land appreciation. The land capital has brought huge wealth in the resale, but the old miners who stayed in the mining villages, including the aborigines who entered the field in the 1980s, are facing displacement, and temporary tribes living on the edge of the city live together by the river. , such as the Sanying Tribe and the Xizhou Tribe, were forced to relocate by the local government at the beginning of the next century. These problems are not over until today, and the article also proposes a struggle in 2021 at the end, pointing out that after the Haishan Coal Mine disaster, there are still many miner families who have not received subsidies for 30 years.

My second question is, although the author said at the end of the sharing that nature has reclaimed the mines, the remaining practical problems such as occupational diseases, compensation, and housing are still closely related to the families of the miners. How does the author’s writing communicate with reality?

Debbie:

Regarding the writing of women, I initially wanted to use the perspective of ordinary people to easily identify "who is the bad guy" in the story. For Grandma, the first bad person is Azu (Grandma's mother-in-law) who abused Grandma, and the second bad person is my Abba (from grandma, mother and me standpoint). If the "bad person" refers to the person who causes the suffering of other people's life experience and dominates the life of others. But writing and writing makes me reconsider whether hateful people must be pitiful.

When I learned about Azu's story, I found that Azu was a woman with her feet tied and unable to be free. She had to rely on her husband, but both husbands died unexpectedly. Everyone regarded her as a broom star. Going back to her context, she was very dissatisfied with the sweetness of her son and daughter-in-law when they were newly married, and blamed her son's death on her daughter-in-law (grandmother). Later, Azu was bedridden in the dormitory without anyone to take care of her (life was so poor that there was no labor force to take care of a bedridden patient), and her later years were actually quite miserable. She is a poor woman made by the times, with more sympathy than hatred, and I hope she is not simply seen as a bad person.

Another "bad guy" was my father, who forbade my mother to go back to her parents' home. I also saw my father's verbal and physical violence towards my mother when I was a child, and hated and feared my father. The comparison of patriarchy between generations was also written, but now that my father is still alive, I don't think this part should be written. But in the process of writing, I found that my father also came from a miner's family at the bottom. He was an orphan and widowed mother since childhood. He was bullied and could only vent on his mother in the end. To some extent, the plight of my father is actually similar to that of Azu. I finally removed the father part, which is also the limitation of self-disclosure in "reflexive writing". What I can understand myself may not be what everyone can understand when I write it down. The twists and turns in the middle are actually to protect my family.

There is also a "bad guy" who seems to be my uncle. He eats, drinks, prostitutes and gambles, wastes a lot of money, and ends up in debt. He escaped several mine disasters, but was never able to find a suitable job, and was later affected by pneumoconiosis. But in his veins, he can also see children who have lost their parents growing up with the experience of middle-aged and elderly miners, eating, drinking, prostitution and gambling. When I go into their life experience and understand their background, I am not willing to bully the weak and look at these people at the bottom who are shaped by the environment with a critical perspective.

As a sociologist and activist, after writing this article, I feel that there is still more to do. For example, after the three major mining disasters, the public donated more than 300 million yuan to charity, but these donations were not distributed to the miners who were affected by the disaster, so that when my grandmother fell ill, she had no money for treatment, and she had to rely on my mother. Go to the hospital to pay for medical bills. Last year (2021), I saw some miners asking the government to subsidize the miners’ allowances, including the previous donations, how the country will redistribute them. I hope I can do more things. After revealing the truth, I will transfer the donations that should belong to the miners’ families. Give them back.

"Present" host:

In the words of Mr. Dai in his off-site notes, "The completion of this work is not the end of a personal life narrative, but the beginning of a new social action." Our second issue still insists that the theme of "presence" is to be at the scene of the times , taking writing as action. Mr. Dai's work is a good response to our philosophy.

During the first "Presence" call for proposals, we received quite a few proposals for writing personal life histories, such as writing the history of a family, or going back to one's own village. When we read proposals, or talk to writers, we discover that the first difficulty in writing personal life histories is authenticity.

Salvage the truth from history, and personal memory will also be somewhat alienated due to the age. How do we screen in writing, and how do we ensure that writing does not deviate from the truth? How to build the authenticity of non-fiction writing beyond dictation?

Gu Yuling:

Memory is inherently unreliable, and neither is history. The truth is impossible to reproduce, because of differences in perspectives, limitations of vision, confrontation of interests, and the time difference between oral and factual occurrence, etc., non-fiction writers can only exhaust all possibilities to approach the truth. According to the current research and knowledge, Write the best story you can tell.

In my opinion, entering the field is a process of "discovery", in which contextual and meaningful connections and narratives are connected between different factual fragments. The horizon of memory has its limitations, and people sometimes justify it and rewrite the past for the benefit of the present.

Non-fiction writers try to reconstruct facts based on historical materials, oral narratives, and return to the field, but this fact "discovered" by the narrator is only a possibility close to the truth, and should not monopolize a single truth. The writer can only guarantee that no character or plot is fabricated for the purpose of rationalizing my inferences, acknowledging the limitedness of our knowledge, and acknowledging that there are far more unknowns than known, but all the responsibilities can only be the author after all. Be conceited, because the interview subjects' interpretation of their life course has actually been reinterpreted by the author.

Debbie:

Authenticity is indeed difficult to determine, and I actually do two things. One is to use other members of the family (such as mothers) to supplement the parts that respondents (especially older respondents, such as grandma) forgot or misremembered. The second is through newspapers and magazines, to understand whether it is true or not, corresponding to personal experience. I also think truth is difficult, but the author has an obligation to present truth that has been tested by different sources.

Gu Yuling:

I would add that fieldwork, making a dual chronology of personal and historical is very important. Sometimes, respondents think that it is just a matter of personal luck, such as being laid off in a certain year, but if you look at the historical chronology, you will find that this is not a single case, but the government's economic policy, the fluctuations of the international stock market. The wave of unemployment that came, where one person lost his job, reflected the end of the entire mining industry.

"Present" host:

The two teachers proposed two methodologies, cross-validation and dual chronology. For the author, "don't monopolize the truth" is also an important reminder.

Readers asked in the question, if we are already in the story, how do we deal with complex emotions and how do we achieve self-disclosure?

Debbie:

On the issue of family affection, I dealt with my mother's dissatisfaction with Mamaw's second husband in the article. My mother had a good relationship with my adoptive father (grandpa), so it was difficult for my grandmother to be "transferred" and be with another man. I have heard my mother's negative comments on my grandmother's second husband since I was a child, but back to what my grandmother and uncle said, I think it was my mother's "prejudice". When confronted with such conflicts, I would switch roles, detach myself, and juxtapose and retain different perspectives and feelings. Sometimes I'm an insider, sometimes I'm a bystander. Perhaps this can maintain objectivity and allow a distanced observation of family conflicts. Of course, at this time, the author must remain rational and cannot stand on one side emotionally to express his support or opposition to a certain party.

With regard to self-disclosure, I feel that there are certain things I don't want to write about, don't write about. I hardly wrote about my father. Actually, before writing, I didn’t know my father’s family background, I didn’t know that my grandfather and grandmother were also miners, and I didn’t know that my grandmother went to work in a mine. The bottom family is actually secretive. Parents desperately expect their children to turn up in the class and don’t want their children to take care of family affairs. When I became a successful university professor, I was farther and farther from my origin. When I entered middle age and saw that my father was an old man in his 80s or 90s, he could already understand him and reconcile with him. This may be the reaction of a certain generation under the common experience or fate.

Also, I didn't see my mother, grandma, or aunt blaming the patriarchy, they just endured it resignedly. As someone from sociology, I immediately think that you have no class consciousness, you are exploited, you are a female victim of patriarchy. But from their perspective, what I see is the resilience of women. In great history, individuals may really have no choice. From the latter point of view, we think they should be this way, they should be that way, but they just couldn't be that way. It also made me re-understand power relations in sociology, and re-think the scope of application of the concepts of perpetrator and victim, dominant and dominated.

"Present" host:

I recommend everyone to read Mr. Dai's off-site notes "The Repair of the Gap between History and Life". When the author is so "present" and so close to the life experience of the interviewees, they can gain a different understanding.

Another reader's question is, if the background of the interviewee is changed in order to protect the privacy of the interviewee, is this still non-fiction writing?

Gu Yuling:

Adopting anonymity, changing the background information of characters, etc., are all means to protect the respondents. The deeper question still needs to be connected to what Mr. Dai discussed before, where is the boundary of exposing the pain of others or oneself? You know there are things written that will hurt the interviewee, and even if you think it's a good story, ethically, you probably shouldn't write it.

But I also want to use Mr. Dai's father's story as an example to illustrate the boundaries of exposure. There is very little writing about her father in this article, but as De Bofen just mentioned, she has a process of understanding her father. I believe that if there is enough space to restore the complete story of her father, she can leave a context, She may not be reluctant to expose the writing of flesh and blood. What I want to say is that all simplified writing will make people fall into binarization and labeling, and for non-fiction writers, you are close to the lifeline of this person, if you can only write in such a limited space, and If it may create a misunderstanding, then it is better not to write. But that doesn't mean it can't be written, it just requires conditions, complex thinking and narrative, to erase the simplified "bad thing" label. We will understand that the so-called "bad things" are under certain time and space conditions. If you make his situation clear and say how many choices he had at the time, or he didn't have to choose at all, you have a more three-dimensional understanding of people, then His writing is not to expose his pain, but to expose the difficult situation of man.

All writers may know that when you write something hesitant about and you are not convinced, it may be that you have insufficient information to verify, insufficient depth of understanding, and insufficient space to accommodate. At this time, you must give priority to protecting the interviewee. . It would be unfair to write it down when knowledge and insight are not enough, and let it become history. "Do not monopolize the truth" also has this meaning. We ourselves are constantly exploring and growing. The writer does not give an answer, but proposes temporary inference results in the process of searching and inquiring. ,

"Present" host:

Another reader asked an interview operational question , how to get into the details through an interview if it is difficult to imagine the scene just relying on the interviewee's description?

Debbie:

This is a good question. I have never been in a mine. I have looked at photos, historical materials, site sites, poems and novels, because it is difficult to imagine a scene based on text descriptions alone. But I have a small advantage in writing: because Mamaw is illiterate, what she has in her mind is not words, but images, so she can tell the scenes of her work in detail. This is also an accidental gain in the writing process.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…