I know nothing.

Shen Aidi: How was the historical memory of "arrogance and ignorance" formed in modern China?

The copyright belongs to the author, please contact the author for reprinting in any form. Author: Princeton Reading Collection (from Douban) Source: https://www.douban.com/note/831898995/

Editor's note: When people search for the origin of modern Chinese tragedy, they often think of Emperor Qianlong's arrogant attitude towards the Macartney Embassy in the United Kingdom, believing that the "celestial" mentality represented here hinders China's modernization. The "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" has long been regarded as a manifestation of the arrogance and self-reliance of the rulers of the Qing Dynasty.

In Princeton University Press's new book, The Perils of Interpreting, Oxford professor Henrietta Harrison portrays the lives of two translators in the Macartney mission, showing that pre-Opium War China's "arrogance and ignorance" was a semi- artificially created over the centuries, not an inherent trait of the rulers or the culture of a society. And Professor Shen Aidi's article The Qianlong Emperor's Letter to George III and the Early-Twentieth-Century Origins of Ideas about Traditional China's Foreign Relations focuses on the historical document "The Qianlong Emperor's Letter to King George III". This paper studies how this historical perspective of the "arrogant and ignorant" rulers of the Qing Dynasty came into being and what caused it to endure.

This post is a Chinese translation of this paper, "The Emperor Qianlong's Letter to King George III and the Formation of Views on Traditional Chinese Foreign Relations in the Early 20th Century". Professor Shen Aidi emphasized in the article that archival materials are often important materials for historical research, but the positions of the archives compilers, disseminators, and interpreters themselves, as well as their political background, will affect the writing of history. The use of research archives not only helps us understand the different voices in history, but also helps us to think deeply about the history of political transition and diplomacy, the power considerations behind historical writing, and the shaping of reality by ideas.

This article is reproduced from the public account "Global History Center of Capital Normal University". The article was originally published in the 20th series of "Global History Review", translated by Zhang Li and Yang Yang.

The Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III and the Formation of Views on Traditional Chinese Foreign Relations in the Early 20th Century When Lord Macartney led a British mission to China, a passage from the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England":

"The Celestial Dynasty cares about the four seas, but it is hard to govern and manage government affairs. The rare treasures are not precious. The king of you brought in all the things this time, reciting their sincerity and offering them a long way, and specially ordered the yamen to receive them. King of all countries, all kinds of precious things, all of which are all in the collection. You see it yourself by the envoys and others. However, it is never expensive and clever, and there is no need for things made by your country."

Since the 1920s, the above passage has been widely quoted by historians, international relations scholars, journalists, and teachers to illustrate the traditional Chinese misunderstanding of the rising power of the West: Emperor Qianlong foolishly thought that George III was paying tribute to him, and his disparagement of British gifts was seen as a rejection of Western science and even the Industrial Revolution; traditional Chinese foreign relations associated with tribute and embodied in kowtow ceremonies, and emerging European countries Equal diplomacy between the two countries is in stark contrast. The broad interpretation of Qing political culture implied in such conclusions has been criticized by experts for years. However, how did the traditional interpretation of the above citation come to be? What is the reason for it to endure?

Extensive reading of the Qing historical archives shows that the widely quoted text does not represent Qianlong's real response to the British mission, which Qianlong viewed primarily as a security threat; Etiquette concerns, and their impact on Chinese and Western scholars when Qianlong's imperial edicts began to circulate widely in the early 20th century. An examination of how the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" was interpreted shows that both the editorial choices of historical archives and our view of Qing history today are still influenced to a certain extent by changes in China's political situation in the early 20th century.

Criticisms of using a passage from Qianlong's imperial edict to characterize premodern Chinese foreign relations have been around for years. This criticism focuses on two types of studies: first, the study of the influence of Western science on the Qing court; second, the study of the Qing Dynasty as a dynasty of Manchu conquerors. Scholars who study the history of Jesuit priests in China have long pointed out that the Qing court was very interested in Western astronomy and mathematics. Emperor Kangxi studied Euclid's "Principles of Geometry" and other mathematical writings under the guidance of Jesuit priests, while his grandson, Emperor Qianlong, had an extensive collection of European-made clocks, automata and astronomical instruments. In the influential essay "China and Western Technology in the Late Eighteenth Century," Joanna Waley Cohen discusses what the early Qing emperors had to do with the Jesuits. The clergy offered a study of European military technology interest, and Cohen believed that Qianlong's emphasis on China's cultural superiority and self-sufficiency in the above citation was motivated by domestic political considerations. There are also scholars, who use Manchu and Central Asian language documents for their research, and argue that although Qing emperors used Confucian institutions and philosophies to manage their Han subjects, they did not impose these ideas on the frontier peoples of their empire, but rather According to the cultural system and ideology of the frontier peoples, the relationship between the Qing court and them is constructed. Laura Newby argues that the Qing Dynasty also followed this principle in its foreign relations with Central Asia, and did not always adopt the Confucian concept of the tributary system for these regions. More recently, Matthew Mosca argued that 18th-century Qing officials had realized that they were part of the global trading system, and knew that Britain and Russia were important players, and that the Qing insisted on doing business with one mouthful because the Qing The original institutional structure gave local officials such as the Governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, the Governor of Guangdong, and the Guangdong Customs the power to supervise the handling of diplomacy.

Although the above studies challenge traditional interpretations, the perception of Macartney's visit to China as we know it remains deeply influential. In research by James Hevia and Alain Peyrefitte in the 1990s, both culture and etiquette were placed at the center of explaining the Qing emperor's response to Britain, although in other On the one hand, they are completely different in their approach and arguments. In addition, the quotation from the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" remains a familiar way for the public to learn about China. Students in high schools and colleges continue to analyze it, and journalists still cite it; it is also used by current international relations scholars as a historical example of how the international community thinks today, that China-centric Asian diplomacy is The basis for a new interpretation of international relations in Asia today.

01 Where does the influence of the relevant interpretation come from? The above quotation is very influential mainly because it is the original text of the emperor in an important diplomatic document. However, over the years there have also been calls for a critical look at the political process of how historical documents are pushed to historians. It starts with the fact that some scholars today are working on different topics than those who wrote and compiled the archives before. Social historians search for the lives of silent groups in the hope of uncovering underlying information from reading historical documents that differs from the surface text. Further thinking led to Ann Laura Stoler's view that archival compilation is both a record of politics and its power to shape it. In this regard, Kirsten Weld specifically examines how institutions that archive the oppression of people (and hide that oppression) can thwart those seeking redress. The study of how archival materials are used will not only help us understand the voiceless groups, but is also valuable for the study of politics and diplomacy, especially after major political transitions that require a reconstruction of past history in order to legitimize the present. Require.

After the Revolution of 1911, the Qing court archives were no longer used as an anthology to provide information on court decisions and praise the emperor, but instead were used as a source of data to explain the rationale for the fall of the Qing Dynasty. Crucial to this process is the work of a group of Chinese scholars. In the 1920s, when they published the "Paper Story Series", the political situation at the time affected their selection of data on the Qing history of the Macartney mission to China, and these selections became authoritative historical data. In particular, in compiling the archives of the Macartney mission to China, these scholars focused on those documents that showed the Qing court's attention to rituals and etiquette, while ignoring those related to the Qing court's military response to the British threat and these historical texts were disseminated to Western readers through Fairbank's research. Fairbank wanted to use the Chinese archives to balance the popular views of Westerners on China's diplomatic history at that time, but his emphasis on Chinese archives also meant that his research would be seriously affected by the choice of archival materials, and the archival materials he came into contact with were After being screened by Chinese scholars who managed the Qing historical archives at that time, the part of the historical materials that was made public to historians.

Terry Cook calls on historians to seriously consider the role of archivists as historical "cocreators" who can decide which records to keep and which to exclude. In the case of the Macartney mission's visit to China, the "Employment of British Ambassador Macartney" in the "Paper Story Series" published by the archivists of the Republic of China in the 1920s was not published until the 1990s. It was replaced by the more abundant "Compilation of Archives and Historical Materials of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China". These Chinese archival compilers in the early 20th century were all influential intellectuals, and the large amount of existing materials and research also makes it possible to study their attitudes and actions in the process of compiling archival materials. A careful study of the historical documents related to the Macartney mission in the two sets of archives, "The Compilation of History" and "The Compilation of the Archives of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China", not only enables us to interpret the British mission's visit to China from a single one. The well-known story of the feudal rites turned into a story of the Qing court's military response to the British threat, and it also shows us the important force of material choice in the editing process of the archives; the force that shaped what we told ourselves and the history of others.

02 What is the truth? The popular interpretation of the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" is surprisingly little similar to the reaction of the Qing court at the time, which can be found in the Beijing First Historical Archives' 1996 "Book of History". Seen in Compilation of Archives and Historical Materials of British Ambassador Macartney's Visit to China. Since the Qing historical archives are far from being completely preserved, the Compilation of Archives of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China does not include all the archives at that time, nor does it include all documents related to the research of the Macartney mission, but only selects information concerning missions. Despite this, the "Compilation of Archives and Historical Materials of the British Ambassador Macartney's Visit to China" has collected more than 600 relevant documents, including the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III" containing the above quotations, as well as the Emperor Qianlong's thanks to Britain for the gift Letters in Serge Gowns. The Compilation of Archives and Historical Materials of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China is compiled according to the entire archives, but there is a convenient catalogue that people can refer to in chronological order.

If we read the "Compilation of Archives and Historical Materials of the British Envoy Macartney's Visit to China" in chronological order, the story begins with a letter: this is a letter written by the British East India Company to the Governor of Guangdong and Guangxi in October 1792. Inform the King of England that he intends to send an envoy to congratulate Emperor Qianlong on his birthday. This was followed by numerous documents exchanged between the court and officials as they waited for British ships to appear in the coastal provinces of China. In late July 1793, the mission arrived outside Tianjin, and the members of the mission traveled to Beijing by boat, then crossed the Great Wall, and went to Chengde Mountain Resort to visit Emperor Qianlong. There were many official correspondence between Emperor Qianlong and his officials. Most of these documents are about itinerary, and there is also a lot of discussion about gifts brought by the UK: asking the British to provide a list of gifts, and how the gifts are delivered, assembled and displayed, and some are about the etiquette of the embassy when they visited the Qianlong Emperor. During the discussion, only a few documents mentioned the issue of kowtow, and several of them still accused Zhengrui of being arrogant and fancied that the ambassador should kowtow to him.

The Macartney Mission to China The turning point occurred at the end of September 1793, when two major events occurred. First, after the mission returned to Beijing from Chengde, Qing officials began arranging their southward journey to Guangzhou; second, a series of British requests were translated into Chinese. When Emperor Qianlong read these demands, he was very unhappy. The British not only wanted to stay as permanent ambassador in Beijing (in order to bypass the supervision of the Governor of Guangdong and Guangdong and Guangdong Customs), but also wanted to trade with Beijing in the coastal ports, and demanded tax relief, and at the same time asked for an island in the Zhoushan archipelago near the port of Ningbo and demanded A base is established near Guangzhou. These requirements had significant political and financial implications, and the emperor was, of course, quickly aware of this. So the formulaic edict that had been written to the King of England was thrown away, and a new edict was drawn up at the emperor's personal instructions. The newly drafted edicts state and reject all requests made by the mission. Although many readers believe that Macartney was rejected because he refused to kowtow, leading to the anger of the Qianlong Emperor, the edict does not address kowtows or any other etiquette issues, but instead focuses on the statement of various requirements of the mission and rejected on. This edict is the source of the famous quotation in the preceding paragraph. In that quote, Qianlong on the one hand downplayed the British gift; on the other hand, he emphasized his own generosity. The edict was officially handed over to Macartney, and the embassy left Beijing in a hurry.

After this, in the surviving trove of documents, the main concern was how to avoid the possible military consequences of rejecting British demands. Just before the mission left Beijing, the Military Aircraft Office issued an important edict to the governors of the coastal provinces. In the decree, Emperor Qianlong told the governors of the provinces what happened, and warned: "English is relatively strong among the Western countries, and now it has not done what it wants or caused a little trouble." He then urged the governors to strengthen their defenses, and instructed Canton officials should not give the British any excuse for military action.

"Now that the country wants to allocate trade to the offshore areas, the maritime frontier will be sent to the frontier. It is not necessary to rectify the army, and it is advisable to take precautions. For example, the islands such as Zhushan in Ningbo and the nearby islands of Macau should all take care of the situation. The first picture shows that the English barbarians will not be allowed to sneak in and occupy. … Then the Guangdong Customs should collect the barbarian merchant tax according to the rules. The British merchant ships come to Guangdong more than other countries. It is inconvenient to cut their taxes abruptly, and it is also not allowed to float them in the slightest, so that the barbarians in the country can make excuses.”

Immediately following this edict, there were echoes of local officials reporting that they had taken various actions in accordance with the order. There were also many questions about how to get rid of the five British warships that were moored in Zhoushan at that time, especially the heavily armed "Lion" ship. Zhoushan Island has a deep-water harbor, which is one of the reasons why the British hoped to establish a base there. Macartney once explained that many sailors were sick and needed to rest on the island. This was indeed the case, as a severe dysentery outbreak aboard the "Lion" resulted in many deaths. Emperor Qianlong accepted their request to rest on the island, but at the same time urged local officials to let the British ships leave as soon as possible. Captain Ernest Gower recorded in his logbook that they were driven south by Chinese ships and locals threw dirt into their wells as they sailed south along the coast of China. leaving them without clean water. They showed their power by firing their guns, and Chinese ships docked at the port also fired their guns from time to time. There are also memorials reporting to the emperor how they displayed military might to the British embassies that were sailing south (these also appear in the British records, which mention a large number of soldiers patrolling along the way, and showing them to the Qing soldiers The cannon made a dismissive comment.)

Mixed with these decrees of Emperor Qianlong, there are also a series of memorials written by Song Yun and Aixinjueluo Changlin. Song Yun was responsible for the reception of the mission, while Changlin accompanied the mission to Guangzhou and took over as the governor of Guangdong and Guangxi. Take over the mission's escort work in Zhejiang. Their task was to negotiate trade with the embassy, on the one hand to dissuade the embassy of causing trouble, and on the other to make no concessions to the demands of the British. From Song Yun and Chang Lin's memorial to Emperor Qianlong and Macartney's report to Henry Dundas, the British Home Secretary, it can be seen that Song Yun and Chang Lin were very successful. The general impression from the archives is that, in the mind of Emperor Qianlong, an effective military and diplomatic response to British demands was far more important than the kowtows and other matters of etiquette discussed before the Macartney mission arrived in Beijing .

Throughout the 19th century, Chinese accounts of the Macartney mission also presented a similar narrative. The Qianlong dynasty in the Qing Shilu is largely compiled from documents from foreign dynasties, and lacks some of the military details that can be found in the emperor's private decrees to ministers. Nonetheless, the editors' compilation of the historical materials of the Macartney Mission's visit to China was relatively fair, including the "Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III of England" and the emperor's decrees on military operations. Before the 1930s, Qing Shilu was only open to a very small number of readers; some works published in the context of the Opium War also emphasized British territorial claims and the Qing military response. "Guangdong Haiphong Collection" (1838) contains the official edict of Emperor Qianlong to the King of England, as well as an edict that Emperor Qianlong wrote to his officials in response to British demands, with a tougher stance, as well as his decree to Song Yun. Edict of how He Changlin should respond in military and commercial terms. In addition, another stern decree from Qianlong is contained in the Records of Guangdong Customs (1839), emphasizing the importance of not allowing the British to occupy the islands, and ending with an decree establishing coastal defense. The same theme emerges in a history of Qing foreign relations published in the 1890s, placing the Macartney mission in China at the time of the Qing's victory over the Ghurkhas and successful border negotiations with Russia. Against the background of a powerful dynasty. In all Qing Dynasty literature, the Macartney mission is seen as a defense issue, with emphasis on military preparations and the management of British trade in Canton.

03 What is the origin of the so-called "competition of etiquette"? Since the Qing court saw the Macartney mission as a military threat from Britain, how did the popular view on "ceremony disputes" come into being? To understand this question, we must first look at the British literature of the time. Emperor Qianlong seemed to know very well what kind of etiquette should be used for foreign envoys, and he was more flexible, at least he did not ask his officials to conduct some kind of informal conduct with Macartney at the Chengde Mountain Resort outside the Great Wall, far from the capital. During the audience, a full set of kowtow etiquette is implemented. By contrast, Europe was in the midst of a historical context in which relations between rulers were changing dramatically, and diplomatic etiquette was at the heart of negotiations over how those relations should change.

Scholars of early modern European history have pointed out that although the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 is often considered to mark the beginning of the equal diplomacy of sovereign states, in fact, the concept of sovereignty developed gradually until the 18th century, The old palace hierarchy system still exists. As DB Horn remarks in his distinguished study of British diplomacy: "The 18th century [diplomats'] emphasis on etiquette seems to be too much for today's writers." He points out that this period of European powers will not accept ambassadors from other countries unless they are of equal national power. At the same time, he described in detail how it is difficult for different countries to send ambassadors to each other due to etiquette and privilege issues. One example is that the Habsburgs, as rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, refused to grant the title of "His Majesty" to the King of England because he was only a King and not an Emperor. This made it difficult for Britain at the time to send ambassadors to Vienna. The "American Revolution" and the "French Revolution" exacerbated this problem because the powerful new states they created were republics, traditionally the lowest-ranked entity in the court hierarchy. The American Revolution and the French Revolution also brought the Enlightenment idea of "equality" to the fore politically; before that, the idea was mainly directed at the individual, but now it is beginning to extend from the individual to the nation. However, even in the 1790s, this idea was still controversial. After the Macartney embassy returned, Thomas James Mathias published a poem he claimed was a passage from the "Edict of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III of England" In translation, Emperor Qianlong condemned the leaders of the French Revolution in the poem:

"Above the shocked world! The banner of vicious equality is unfurled, the blood is in the air, and the words on the banner: fraternal freedom, death, despair!"

Mathias was a member of the Queen's Chamberlain and a satirist. His anonymous attacks on the literary personalities of the time and French intellectual circles were widely welcomed by conservatives. Equality, as the poem suggests, is far from universally accepted, if only as an ideal. The etiquette of equality among nations was not accepted until the "Congress of Vienna" in 1816. Even so, this ideal, like the ideal of the Chinese tributary system, has not been put into practice.

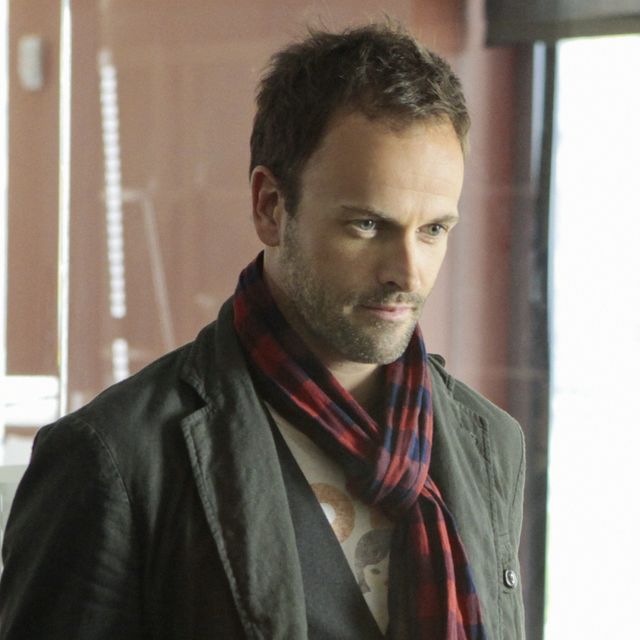

Portrait of Thomas James Mathias (c.1754 – 1835) In the context of hierarchical diplomacy still recognized as a diplomatic relationship in Europe, the British had already begun to pay attention to the etiquette of the Chinese emperor before the British embassy before the embassy left London. It's no surprise. Macartney, in his letter to Dundas, had anticipated the imminent problems of "kneeling, prostrating and other boring Eastern rituals" and said he would deal with them nimbly. In James Gillray's famous cartoon "The Reception of the Diplomatique and His Suite at the Court of Pekin", the Englishman is reclining in a It is often used to show the importance of kowtowing to the Chinese reception of the Macartney mission. In reality, however, the painting was published long before the mission left London. This painting represents not China's attention to etiquette, but the British public's attention to the body posture of British diplomats, and has become a core criterion for judging the success of the mission. Macartney's frequent references to etiquette, especially the issue of kowtow, in his diary expressed his anxiety and apparently to record how carefully he handled the issue. John Barrow of the Macartney Mission wrote an influential book on the mission, in which he emphasized that Macartney had refused to kowtow, claiming that it was in fact the Chinese who were responsible for etiquette issues Too rigid. In this regard, Laurence Williams believes that Barrow's expression precisely reflects the influence of British satire on the description of the mission by later generations, who hoped to subvert satirical criticism through defensive description.

The Reception of the Diplomatique and His Suite at the Court of Pekin© The Trustees of the British Museum This attention to etiquette continued to appear in nineteenth-century English writings on the Macartney mission, as diplomatic etiquette was still the concerns of the European powers. Westerners value the form of etiquette in their diplomacy with China, and their diplomats refuse to follow Qing etiquette, saying they are not representatives of the tributary state. On the Qing court's side, it was oscillating between—or rejecting the reception altogether, unless members of the embassy accepted a kowtow ceremony—or adopting an alternative ritual that avoided a formal reception. In 1816, the British sent a delegation led by Lord Amherst to visit China. The Qing court refused to receive them unless the members of the delegation accepted the kowtow ceremony; however, in the late Qing Dynasty, several times the court adopted a method to avoid formal reception—— - The British therefore do not have to kowtow - to receive the British envoy in an informal ceremony. In Britain, the political importance of etiquette continued to grow, as reflected in James Bromley Eames's influential general history The English in China, published in 1909. China); the book criticizes Macartney's haphazardness in kowtowing and, in the author's preface, dedicates the book to a British officer in the Eight-Power Allied Forces. American William Woodville Rockhill published an article on kowtow in the newly founded American Historical Review in 1897, "Foreign Mission to China: The Question of Kowtow," 1900 He was appointed as the U.S. Plenipotentiary to the "Executive Committee for Reforming Qing Diplomatic Etiquette." It can be said that until the Revolution of 1911, the etiquette of the Macartney mission to China was the focus of Western attention, while the Chinese literature emphasized the threat of the British and the military measures taken to deal with it. .

At that time, the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" was not widely known. The English translation of the decree has long been forgotten in the archives of the British East India Company, even by the tireless Hosea Ballou Morse in his 1910 History of the Foreign Relations of the Chinese Empire. There is no mention of this edict. The original copy of the edict can be found in documents on the defense of Guangdong Customs, but it did not attract attention until the 1884 book "Continued Records of Donghua". In 1896, Edward Harper Parker translated into English the imperial edict of Qianlong, which was extracted from the "Continued Records of Donghua". Parker's interest at the time was to use these new sources to study the Gurkha Wars of the 1790s, and although he published a translation of the Qianlong Edict in a London magazine, it did not elicit any particular response.

It was the demise of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the rise of nationalism that brought the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" to fame. In 1914, two British writers living in China included the English translation of Qianlong's imperial edict into their unofficial history of the Qing Dynasty. It is from this English work that Chinese scholars selected the "Edict of the Emperor Qianlong to the King of Ying". To them, Qianlong's ignorance and complacency in the imperial edict just matched the Revolution of the Republic of China. Qianlong's imperial edict is one of the famous documents that appeared widely and popular in the research of Qing history before and after the 1911 Revolution. The other is "Ten Diaries of Yangzhou", which vividly describes the brutality of the Qing army's conquest in the 17th century, and has also been translated into different languages for publication. The fact is that the Qing historical archives that historians have obtained through the same process make the interpretation of the revolution particularly effective and durable.

For the British authors, the failure of the Macartney mission justified the existence of British power in China. For this purpose, Macartney's demands were summed up as diplomatic relations and free trade (rather than tax breaks and claims for territorial bases). Morse said: "The modest bill of rights to trade proposed by England in 1793 was realized by force in 1842." British writers began with the Macartney mission's visit to China to describe Sino-British relations. The story of Britain's two attempts to achieve legitimate and equal relations between countries through diplomatic means, but both failed miserably, and then justified the use of force by the United Kingdom against China, while avoiding the substantive nature of the mission in writing Require. One effect of this was to make the Qing Dynasty look more like a reaction to a cultural conflict.

Shortly after the 1911 Revolution of 1911, Sir Edmund Backhouse and John Otway Percy Bland published a book on the history of the Qing Dynasty, The Book The book contains the complete translation of "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England". This is a witty and entertaining bestseller. The book presented the Qianlong Edict to the public, and some people took it as evidence of Chinese arrogance, and then justified the British invasion of China. However, Brand and Sir Beckhouse themselves leaned towards romantic conservatism, and they saw the Qianlong decree as evidence of the Qianlong emperor's greatness, in stark contrast to China's later decline: "Since its rulers have put themselves How quickly and thoroughly the process of the decline and humiliation of this great celestial empire has been since it was described as 'the celestial dynasty cares about the four seas'." Since then, the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong's Letter to King George III of England" has quickly become well known to Western readers. Out of confidence in the cultural superiority of the West, Westerners often ridicule the words in Qianlong's imperial edict. Philosopher Bertrand Russell, who had given a lecture tour in China, had read Bland and Backhouse, and in his own 1922 book The Chinese Question In the book, a long excerpt from Qianlong's imperial edict, and then commented: "No one can understand China unless the absurdity of the edict is no longer present." Arnold Toynbee also in the 20th century Quoting the imperial edict of Qianlong in the 1930s, he believed that "the best way to cure this kind of insanity is to laugh at it" (although he believed that a completely similar attitude existed in the West at the time). Toynbee, like Bland, sees poignant irony in the contrast between China's 18th-century arrogance and contemporary weakness. Readers and authors coincided in their mockery of Qianlong's imperial edict, and some authors tried to find the root of some practical problems in China from the language of Qianlong's edict. Part of the reason for its longevity. Previously, the most expressed view was the vastness and power of the Qing Dynasty under the rule of Emperor Qianlong.

Brand and Beckhouse's work also appealed to the conservatism, national pride, and republican sentiments of many Chinese elites, so much so that Brand and Beckhouse's work was popular within a year of publication. Translated into Chinese. Combining the story of the Qing Dynasty's depravity and corruption with the critique of the Qing Dynasty by the Chinese Westernized elites who constituted China's new political authority, the Chinese translation of this book was a sensation when it was published, and it was reprinted four times between 1915 and 1931. However, to Liu Bannong, a Chinese reader, there is nothing to ridicule about the grand speeches of Emperor Qianlong, which are in line with Chinese tradition, are from well-known classic sources, and are also in line with Chinese diplomatic practices. It is simply incorporated into the book's general textual description of the romance and tragedy of the Qing Dynasty of the past. Inspired by the writings of Brand and Bakerhouse, Liu Bannong decided to translate Macartney's diary, which had just been published. In the preface, Liu Bannong's Macartney and the Qianlong Emperor both showed impressive flexibility in their negotiations, and they are models for China's future foreign relations. However, Liu Bannong's fresh take on the Macartney mission, while welcome, was not considered academic. Translators of Brand and Bakerhouse’s work into Chinese feel they have a duty to point out how unreliable Liu’s views are, because Liu Bannong is a novelist, not a historian.

It was through the popularity of these words that English-language documents about the Macartney mission came to the attention of Chinese historians and archivists. In 1924, the remnants of the Qing Dynasty were expelled from the Forbidden City, and the Palace Museum was established. Subsequently, the archives of the Military Aircraft Department originally taken over by the State Council were transferred to the Palace Museum. At the same time, the Palace Museum also took over the surviving case files in the Palace Museum, including the original memorials of provincial officials. What we know today about the popular view of the Macartney Mission events is only part of a larger project of the past to reshape Qing history based on how the archives were acquired and compiled, It's just that the reshaping of the contents of the Qing historical archives is concealed under the story of struggling to rescue and organize historical materials.

Before the fall of the Qing Dynasty, many documents were lost due to poor maintenance and to save space, plus two sabotages by foreign armies. Later, the Republic of China government that came to power after the 1911 Revolution destroyed some of the archives that were considered useless by the officials of the Republic of China. The decision not to retain some documents, while frustrating for historians, is an integral part of national records management. By the 1920s, in addition to political transformation, Rankean historiography also affected Chinese studying abroad. They began to use archival research as a Western method of scientific research. This method is consistent with the tradition of textual research in the Qing Dynasty. So when scholars found bags of Qing Dynasty archival documents being sold as scrap paper in a market in Beijing, they reported it in the press, giving the archives academic (and monetary) access again. of attention.

However, rescuing the Qing historical archives is only part of a larger project with strong political motives to use these archives to "find" the truth about China's modern history. In other words, it is to create a new history that criticizes the Qing Dynasty. Two senior scholars, historians Chen Yuan and Shen Jianshi, were assigned to head the archives department of the Palace Museum. Shen Jianshi is a well-known scholar who is still known today for his work as an archivist. The two invited Xu Baoheng, who had served in the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China government, to manage the archives. These people have experienced the Revolution of 1911, and they are all members of the Republic of China government. Chen Yuan was a member of the China League of Nations. After the Revolution of 1911, he entered the National Assembly and held a series of government positions in the Beijing government. He is also an outstanding expert in the study of the history of early foreigners living in China, and is employed by the Institute of Sinology at Peking University. In addition, he is a member of the newly established Institute of History and Literature of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Shen Jianshi. Xu Baoheng was an official. He and Chen Yuan were active in the same social circle, and they were both members of the "Thinking Mistakes Society". The society meets twice a month to edit texts and discuss academics. Another member of the society is the historian Meng Sen, who is known for his research on how Emperor Yongzheng ascended the throne through conspiracy—one of the biggest scandals in the Qing Dynasty. Shan Shiyuan, who was Xu Baoheng's assistant, selected and transcribed many documents, was a student of Meng Sen. The personal backgrounds of these new archivists and their circles almost inevitably led them to favor historical documents that would help revise Qing history.

Xu Baoheng first visited the archives in December 1927. Like other people who visited the archives, Xu also had the idea of discovering secrets. He found a box that said, "Yongzheng issued an edict in a certain year, and it is forbidden to open it before the Holy Emperor, and those who violate it will do the righteous law." Xu Baoheng then opened the box and found that there were many small file packets in the box, which were about the case of accusing Chinese literati of anti-Manchu script. He decided at that time to select materials from these archives and publish them. A few days later, he discovered a batch of edicts that Emperor Kangxi had written to a eunuch in Beijing when he was away from Beijing. These edicts were "like family letters from ordinary people", which made Xu Baoheng extremely excited. He decided to place these decrees at the beginning of a new volume of his writings.

Over the next few months, under the guidance of Chen Yuan and Shen Jianshi, Xu Baoheng and his assistants compiled the first volume of the "Zhang Gu Congxian". This volume contains 47 documents related to the Macartney mission's visit to China until the publication of the "Compilation of Archives of the British Ambassador Macartney's Visit to China" in the 1990s. These documents are the records of the Macartney mission to China. The primary Chinese source for the event. Some of these documents were translated into English by John Launcelot Cranmer Byng and published under the title "Official Documents of China for the Mission of Lord Macartney to Peking in 1793". Cranmer Baig considers these documents a "very complete record" of the Macartney mission's visit to China, but in fact they are only a small part of the more than 600 documents in the archives, which were selected for The original structure of the archives, the preconceived positions of the compilers, and the influence of the political background at the time.

04 How did the voice of Chinese academia spread to the West? The Qing history archives about Macartney's mission in "Paper Story Series" were also transmitted to the West through Fairbank. Fairbank emphasized the use of Chinese archival materials and passed on this style of research to his graduate students, who later became the leading American scholars of China studies. Fairbank took the Macartney mission, especially the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England", as a symbol of the conflict between equal diplomatic relations in the West and China's view of world domination, and considered this conflict to be part of modern Chinese history. the driving force behind the development. By using archival materials that were being published at the time, he seemed to use the real thoughts of Qing officials to make his case. However, the archival materials he came into contact with were in fact historical materials selected by Chinese historians, and the results were naturally misleading.

Fairbank studied under Ma Shi, a prominent British archival research expert, but decided to engage in Chinese archival research. In 1935, he went to Beijing to collect information. As an American graduate student with limited Chinese proficiency and lack of connections in China, he had little access to senior scholars in charge of archives at the Palace Museum. Through Jiang Tingfu, Fei Zhengqing came into contact with the archives mentioned above. Jiang Tingfu, a few years older than Fairbank, speaks fluent English, and completed his doctoral dissertation on British Labour foreign policy at Columbia University. At that time, Jiang Tingfu was the head of the History Department of Tsinghua University, and was also very active in politics, and was a member of the new Kuomintang government. In the 1950s, Jiang Tingfu served as the representative of the Republic of China to the United Nations, a role he is perhaps best known for. At that time, he had just completed an influential compilation of archives, "Compendium of Modern Chinese Diplomatic History Materials, 1932-1934".

In his analysis of modern Chinese history, Jiang Tingfu combined his generation's fascination with the cultural differences between China and the West with the English writings' assertion that European countries were pursuing the ideal of equality between countries. He pointed out that China's relationship with foreigners in the north has existed for a long time, but it is not a diplomatic relationship. However, he is also skeptical of the idea that European countries are motivated by the pursuit of equality among nations in their diplomatic relations. In his 1938 survey article on modern Chinese history, he wrote ironically: "The relationship between China and the West is special: before the Opium War, we refused to give equal treatment to foreign countries; after that, they refused to give us equal treatment. .” When the Sino-Japanese War broke out, he wrote wistfully, there was only one important question: “Can the Chinese modernize? Can they catch up with the Westerners? Can they use science and machinery? Can they abolish our family and homeland ideas? Or organize a modern nation-state?"

Fairbank was directly involved in the construction of Jiang Tingfu's thought on the tributary system, and he and Deng Siyu (SYTeng) published a series of articles on Qing history archives between 1939 and 1941. Deng Siyu made a detailed study of the book "The Great Qing Dynasty", which covers multiple topics such as the summary of diplomatic concepts and diplomatic etiquette from diplomatic practice. Relying on Deng Siyu's research, Fairbank and Deng Siyu proposed that the tributary system is mainly to solve trade problems, and etiquette is more important than strength in this system. Different from Jiang Tingfu, they agree with the view that Western countries pursue equal diplomacy among countries, and consider it a cultural feature of the West. However, like Jiang Tingfu, Fairbank is using these topics to address the question of whether China can achieve modernization. A few years later, shortly after the Chinese Communist Party took power, Fairbank argued: "China seems to be more incapable of adapting to modern living conditions than any other mature non-Western country." Fairbank believed that modern life was out of step with Chinese traditions, including ethnic doctrine, industrialization, the scientific method, the rule of law, entrepreneurship, and invention; but his own research has primarily focused on the issue of China's foreign relations and placed it within the framework of the tributary system.

These views on Chinese foreign relations were more widely disseminated among English-speaking readers by the great success of Fairbank and Deng Siyu's 1954 textbook, "China's Response to the West." This is an edited source book that combines some "selected and condensed for the greatest possible meaning" with a highly implicit written narrative. The outline of the book was originally written by Deng Siyu according to the general framework of works on the history of Chinese revolution, beginning with the anti-Manchurian nationalism in the early Qing Dynasty and ending with the victory of the CCP revolution. However, this plan was later scrapped by Fairbank and replaced with "Problems and Backgrounds" as the first part of the book. However, the question that plagued Jiang Tingfu and Fairbank's generation remained: can China modernize? Fairbank reformulated the issue so that part of how the Communist Party came to power could be included.

Fairbank answers this question within the framework of the transition from the traditional tributary system to the modern system of international relations, using the tensions that arise during the transition as a driving force for other changes. The first chapter ends with the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England", but the edict has been severely abridged, and all the words about the main requirements of the British mission have been deleted. "Make objects" becomes the last sentence of the edict. Then, Fairbank added a paragraph of his own to make the effect more prominent. He said: "According to this view, the English and Scots who are about to break through the city gates and destroy the ancient superiority of the central empire are still regarded as uneducated barbarians outside the scope of civilization." It was published in the book along with several other documents on the Macartney mission in the "Anecdote Series", but Fairbank reduced these sources to just one decree, which he used as one of the most famous examples, It is used to illustrate that the Qing court once included Western countries in its "traditional and anachronistic tributary framework".

The Cold War was just beginning when the book, "China's Response to the West," was written, and it addresses an important political issue. As Fairbank said, the rise of Chinese communist power is the most terrifying event in "the entire history of American foreign policy in Asia," so "every smart American must try to understand the significance of this event." Then, he came up with a solution—to understand history. In the introduction to the book, Fairbank wrote that if we do not understand China's modern history, then "our foreign policy is blind, and our own subjective assumptions may lead us to disaster." In his depiction of the fall of the Qing Dynasty because its officials did not understand foreign cultures, Fairbank was also reminding the United States that if Americans were not committed to understanding China, something would happen. As one reviewer wrote: "China is not the only nation to suffer because their leaders are unwilling to accept unpleasant truths. But there is no doubt that they paid a heavy price for it, and we should all learn from it. Be warned.” So this book is both a critique of American foreign policy and a call to strengthen research in this field, a view shared by many university teachers in the ensuing decades.

The book "China's Response to the West" became an undergraduate textbook for generations in the United States and Britain, and is not only still in use today, but continues to influence future material compilation. Using the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" as the basis for the defense of the US's foreign policy toward China is as He Weiya pointed out: using this edict to represent China's culturalism and isolation in the 1960s ism and self-sufficiency. Throughout the Cold War, an entire generation of textbooks used the quote from Qianlong's imperial edict to illustrate the isolation of traditional China from the rest of the world (this argument does not convince the author, since it was the large amount of trade that prompted Macal. Nepalese mission to China). From here, the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to George III" has been quoted in world history textbooks and international relations textbooks over the past two decades to help readers understand China's current attitude toward Southeast Asia. Only here, for the first time, the above quote is no longer brought up as a joke: China's rise means that international relations scholars will be prepared to see Emperor Qianlong's statement in their own way. A new generation of scholars aiming to use the Macartney mission event to challenge much of the Eurocentric scholarship in international relations, pointing out that until the recent modern era, it was often the non-Western countries that set the norms of diplomatic relations, and such studies It's hard not to be sympathetic. However, this approach makes it very easy for them to return to the perspective of European egalitarianism and Chinese hierarchy in international relations. This perspective, born of tensions in the transition to equal ceremonial relations among European nations, was written into Chinese history by Chinese scholars to accuse the Qing dynasty they overthrew of failing to distinguish the importance of ceremonies and reality.

05 What conclusions can we draw from the whole story So what conclusions can we draw from the whole story of how the Macartney mission's visit to China was interpreted? On the one hand, we are looking at the cautionary tale that historians are familiar with: historical context is important when interpreting archival documents, and citing a passage in isolation can be potentially misleading; however, we also need to note that , how archives are made available to historians will affect how historians use them. In an age of massive digitization of archives, a story about the publication of archives may seem irrelevant; however, in a massively digitized archive, when certain archives are selected and others are excluded, And when the user doesn't know it, that means the problem is exacerbated when researchers read in search of certain words.

As we begin to examine the issue of archival omissions in archival material compilations, we see that while Emperor Qianlong was responding to the King's Letter within the formal framework of the Qing Dynasty's specific view of world domination, he was also taking action against Macartney Military threats to missions while avoiding potential economic losses. He rightly felt he could avert immediate trouble by placating Macartney with vague promises of future trade talks, but he remained on high alert. Although the Qing court had extremely limited knowledge of the details of Britain's overseas expansion, Emperor Qianlong and his ministers were clearly intelligent and capable politicians. In addition to reading direct sources about missions, we should also remember that the framework we use to interpret Qing history today was developed in the early 20th century, reflecting the concerns of the time, and that framework shaped the archives that are presented to us. There is still much debate about whether these frameworks reflect Chinese or Western perceptions of Chinese history.

In fact, as we have seen, there has been a lot of communication between English writing scholars and Chinese writing scholars. A more important issue we need to understand is that the political context of the early 20th century introduced the particular problems of that era. "Can the Chinese be modernized?" was the core question studied by Chinese and Western scholars at that time, and the "Edict of Emperor Qianlong to King George III of England" was used to raise the question of "whether China can accept equal diplomatic relations, science and industrialization." Today, such questions are clearly outdated, and China's growing power on the world stage is driving a new round of Qing history rewriting.

This article is reproduced from the public account "Global History Center of Capital Normal University". The article was originally published in the twentieth edition of Global History Review, translated by Zhang Li, professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beihang University; Yang Yang, doctoral student at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Beihang University.

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…