connect the dots.

Why a landline is the perfect tool

Ivan Illich would definitely agree with the internet.

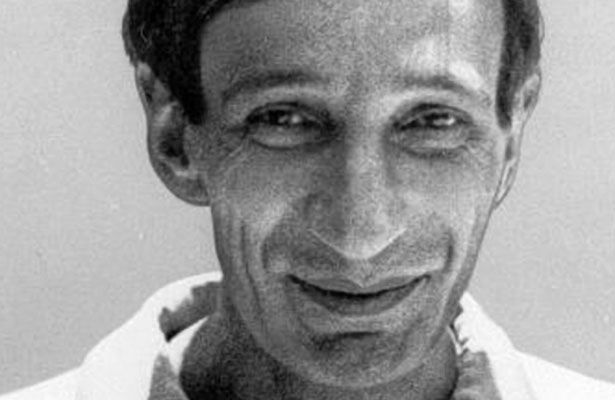

Born in Vienna between the two world wars, public intellectual and radical priest Ivan Illich began to rethink the world in his 30s. In 1961, he arrived in Mexico via New York City and Puerto Rico and founded the Center for Intercultural Documentation (CIDOC) in Cuernavaca, a missionary language school, a free school and a A fantastic combination of radical think tanks, where he brings together thinkers and resources to study how to create a world that empowers the oppressed and promotes justice.

Ivan Illich's achievement is to reconstruct human relationships with systems and societies in everyday, accessible language. He advocates for the reintegration of community decision-making and individual autonomy into all systems that have become oppressive: schools, jobs, law, religion, technology, medicine and the economy. His views had an impact on technologists and the appropriate technology movement in the 1970s—are they still relevant today?

In 1971, Ilyich published one of his most famous books, Deschooling Society. He argues that the commodification and specialization of learning creates a pernicious educational system that has become an end in itself. In other words, "the right to learn is curtailed by the obligation to attend school". For Ilyich, language often points to how toxic thoughts poison our relationships with one another. "I want to learn," he said, has been transformed by industrial capitalism into "I want to get an education," turning the basic human need for learning into something transactional and coercive. He recommends a reorganization of school education to replace manipulative qualification systems with autonomous, community-supported, hands-on learning. One of his suggestions is to create "learning networks," where computers can help match learners with those who have knowledge to share. This skill-sharing model is popular in many activist communities.

In Tools for Conviviality (1973), Ilyich extended his analysis of education to a broader critique of Western capitalist technology. The major turning point in the history of technology, he asserts, is that in the life cycle of every tool or system, the means outnumber the ends. "Tools can rule men sooner than they expect; the plow makes man the lord of the garden but also makes man a refugee in a sandstorm." (Tools can rule men sooner than they expect; the plow makes man the lord of the garden but also the refugee from the dust bowl.) This effect is often accompanied by a rise in power among expert management; Ilyich sees technocracy as a step toward fascism. Tools for Conviviality points to the ways in which a useful tool can evolve into a destructive one, and offers advice on how the community can escape this trap.

So, what makes a tool "convivial"? For Ilyich, "tools foster conviviality to the extent to which they can be easily used by anyone, as often or as rarely as needed, for the purpose chosen by the user." be easily used, by anybody, as often or as seldom as desired, for the accomplishment of a purpose chosen by the user.) That is, "friendly" technology is accessible, flexible, and optional. Many tools are neutral, but some promote friendliness and others kill it. For Ilyich, hand tools are neutral. Ilyich uses the telephone as an example of a "structurally convivial" tool (remember, this is in the age of ubiquitous public payphones): anyone with coins can use it Say what they want to say. "The phone allows anyone to say what he wants to say to whomever he chooses; he can use the phone to do business, to express love, or to stir up an argument. It's impossible for bureaucrats to define what people say on the phone, although they can interfere— Or protect -- the privacy of their communications."

On the other hand, a "manipulatory" tool prevents other options. For Ilyich, the automobile and highway systems are typical examples of this process. Another example is that licensing systems such as compulsory education devalue those who do not receive a license. But these tools, that is, large-scale industrial production, would not be banned in a "friendly" society. "A 'friendly' society is not fundamentally free from manipulative institutions and addictive goods and services, but rather is a balance between those tools that create specific needs and those that facilitate self-actualization." (What is fundamental to a convivial society is not the total absence of manipulative institutions and addictive goods and services, but the balance between those tools which create the specific demands they are specialized to satisfy and those complementary, enabling tools which foster self-realization.)

To promote "convivial" tools, Ilyich proposed a research program with "two main tasks: to provide guidance for the initial stages of detection of murderous logic in tools; and to design tools and tools that optimize life balance. system, thereby maximizing freedom for all." He also suggested that the pioneers of "friendly" societies worked through the legal and political system and demanded justice for them. Ilyich believes that change is possible. There are decision points. We cannot give up our right to self-determination or decide how far is enough. "The crisis I've described," Ilyich said, "is that people are faced with a choice between 'friendly' tools and being run over by machines."

Ilyich’s ideas about technology, like his ideas about schooling, had an impact on those who in the 1970s thought we might be on the cusp of another world. Some of these utopians included early computer innovators, who saw a culture of sharing, self-determination, and DIY as something that should be incorporated into tools.

Computing pioneer Lee Felsenstein talks about the immediate impact of Tools for Conviviality on his work. Ilyich described the radio as a "friendly" tool in Central America, and for him it was a model for the development of computers: "The technology itself was attractive and accessible enough to them that it catalyzed them Inherent propensity to learn. In other words, if you try to mess with it, it won't burn right away. The tube may overheat, but that's ok, it will warn you that you're doing something wrong. The person trying to uncover the secrets of the technology is the same as the technology itself The set of interactions that can exist between the Showed me the way forward. It seems to me that you can do the same thing with a computer." Lee Felsenstein describes the first meeting of the legendary Homebrew Computer Club, where there were 30 Multiple people trying to understand the Altair computer together, it was "the moment when the personal computer became a friendly technology".

In 1978, Valentina Borremans of CIDOC wrote the Reference Guide to Convivial Tools. This resource guide lists many of the new ideas for appropriate technology in the 1970s - food self-sufficiency, environmentally friendly housing construction, new energy sources. But our contemporary friendly tools are mostly in the field of communication. The personal computer, the web, mobile technology, the open source movement, and the maker movement are all tools of contemporary friendliness. What other friendly technologies are we using now? What tools do we need to make us more friendly? Ivan Illich would admonish us to think carefully about the tools we use and what kind of world they are creating.

Compiled from: Why the Landline Telephone Was the Perfect Tool

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…