我們是你從Web2到Web3的旅伴,一起發掘NFT藝術的浪漫。 聯絡我們:c2x3.nftpress@gmail.com

Collect Replicas of the Digital Age by Casey Reas

Foreword by Jason Bailey

In the world of generative art, there are a few people I consider heroes. Casey Reas (and Ben Fry) top the list for inventing the Processing programming language. With Processing, Reas and Fry empowered thousands of artists to create code-based art who otherwise would never have learned how to code, and it cannot be overstated how important their contributions are. Likewise, Reas has been elevating the status of digital art—particularly generative art—in his own artistic practice, exhibiting his work in prestigious museums and galleries around the world.

Now, with his seminal article Collecting Replicas in the Digital Age, Reas is leading the way again, this time on how we think about collecting digital art. Immediately after reading the draft, I asked if Reas could be shared with you as a guest post on Artnome, because that's exactly the kind of leadership this space needs and what I advocate for creating the Artnome site. Therefore, I am honored to share this insightful article by Casey Reas with you.

Collect replicas from the digital age

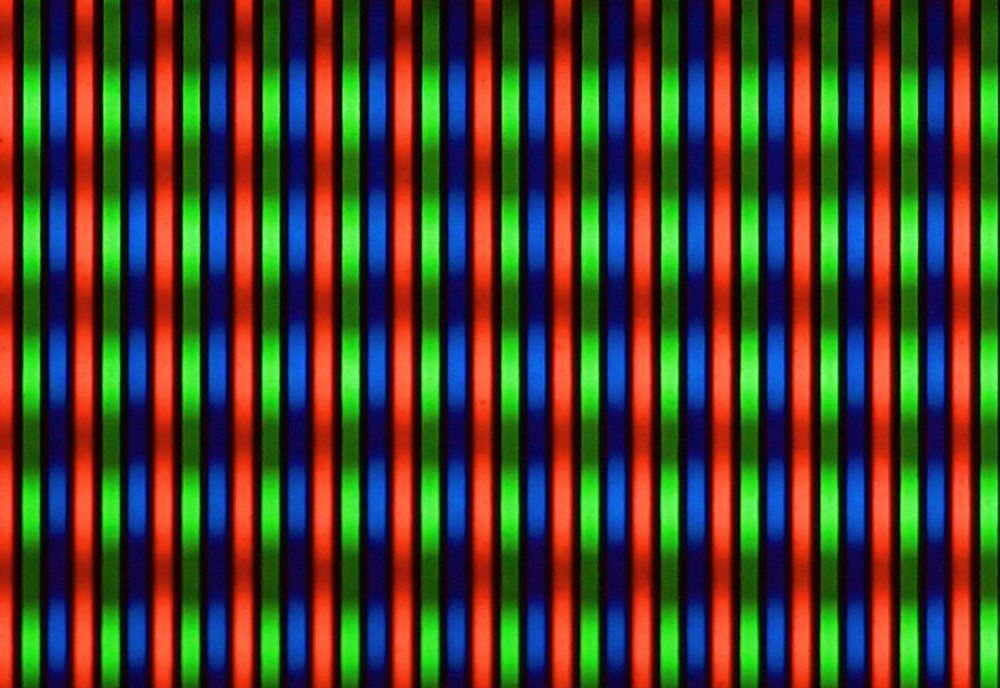

In the art market, almost everything sold is an object, such as a manuscript, a painting, a sculpture, an installation or a photograph, but there are some exceptions. These errors may include a contract, a description, a digital video file or a set of software. These are all examples of art as information rather than material. For example, a purely digital photograph is not the same as a printed photograph or negative. Digital photographs store images as a sequence of colors defined as numbers that can be displayed or projected on a screen. Printed photographs, by contrast, are continuous shades of gray, or color values, embedded into the structure of a sheet of paper.

While more and more works in digital media are created by artists, the art market has been hesitant to collect works that have no physical and tactile nature. In contrast, other types of collections unrelated to the art market have turned to digital, informative archives. The most iconic transition from physical to digital collections is in music. A traditional art collection has nothing in common with a traditional music collection. Works of art are often one-of-a-kind, or limited editions, much smaller than vinyl or CD releases. However, the future of contemporary music collections and contemporary art collections may end up being more similar, not different—this is what this article speculates.

Favorite Archives

The shift to collecting music is one where the media's informational version is more in demand than the physical form -- when people's desire for an album or track's MP3 archive exceeds the desire for vinyl or CD. The catalyst for this shift was a software called Napster and how that software enables people to participate in peer-to-peer (P2P) sharing. This is facilitated by the cultural shift of the Internet and shared media.

When Napster was released in 1999, it opened up a new way of collecting, sharing and trading. Before, people could copy tapes and CDs for friends, but with P2P systems, the scale, speed, and convenience of sharing make this new approach fundamentally different from its predecessors. The distribution system of a brick-and-mortar store is nothing compared to a direct download. Behaviour and thinking about ownership shifted rapidly. In 1999, searching for Aphex Twin made it easy to download the Richard D. James Album and Come to Daddy. People who use the software do not need to pay, nor do they expect to pay. These files are shared by many computers around the world, and they are quickly transferred to any connected computer. This same pattern, time and time again, can lead to hundreds of hours of music being downloaded for no cost. It felt normal at the time, but it wasn't legal. The response from gatekeepers and copyright holders was controversial and punitive—people were sued.

As music distribution transitions from record to tape to disc, the main pattern is the same. Collectors will buy one thing: a grooved vinyl, a tape wrapped around a spool, and a thin polycarbonate loop encased in plastic. Tapes and CDs differ from records in that they are easy to copy. In the case of tapes, they are noisy and the reproduction will degrade; in the case of discs, they are perfect reproductions. However, from vinyl records to compact discs, there is a continuum of patterns in which purchased items become owned. A collector could go to a used record store on Canal Street (New York) and sell her copy of "Remain in Light" because she owns the item. The same collector can also buy a second-hand copy of Dark Side of the Moon that someone previously sold to the store. The complete story of collecting records, tapes and CDs has another meaning. Because these items become property after being bought, the owner can lend them to others whenever he wants. "The Queen is Dead" can be loaned to a friend for a few weeks, and if she likes, the tape can be exchanged for "Three Imaginary Boys." This whole system is flexible and legal, and it works well.

Today, people still buy CDs, cassettes, and records, but the new options are more dominant and, perhaps more importantly, more convenient. Streaming services offer extensive, but still limited, music libraries. When buying music, it's usually a digital archive, either one song at a time or an entire album of tracks. However, if a song is purchased as a digital archive, the price is 99 cents, which is not the same as buying a used cassette single for the same price. Cassettes are property, and digital archives are licensed. The license states that the music does not belong to the person who bought it. The person has no right to lend it to someone else or resell it. In fact, the person doesn't even have the right to give it to someone else. It's legal, but it doesn't feel right. This is the age of the arcane end-user-license agreement (EULA) that defines what we can and cannot do with the media and software we pay for, but not as property.

Focusing on music , it clarifies the difference between ownership and licensing. Additionally, music was the first strong media industry threatened by downloadable digital media, followed by film/audio and then publishing. There has been an interesting turnaround over the past two decades, and it now feels like things have largely settled down.

New collections, new media?

So far, this discussion has raised some difficult questions to answer. Can accessibility be part of art collecting, or is it counter to what attracts people to collecting? Would people still be interested in art if it wasn't exclusive or a sign of status? Will the audience for existing art collections change, or does a new collection need to create a new audience? Can or should the audience for collecting art expand to millions?

The kind of collections in which people participate widely, such as music, cards, and comics, are only possible when the work is mass media, which means that people collect items that are distributed in infinite or large quantities. As mentioned above, this collection may only apply to property, not authorized things. The people who collect these things need to have the right to sell them, trade them, and give them to others.

Some visual artists working in media such as video and software are envious of this type of collection, but also have conflicting feelings. These artists wanted the works to be available to anyone who wanted to collect them, but they also realized that the advantages of the gallery system were in direct opposition to this goal. On the one hand, artists don't want to prevent people from collecting works because of cost barriers, but artists often have specific requirements on how to control the display of works. For example, some works need to be viewed in precise lighting conditions and in specific proportions. Works with these requirements are not mass media, but are created for unique physical spaces and can only be created in controlled environments, such as galleries or museums. The traditional gallery system also supports its artists through administration—responsible for sales, paperwork, publicity, shipping logistics, and press communications. These services exist only to sell unique or editioned high-priced titles.

In theory, an artist might decide to make one work for a gallery and another for mass communication. This decision may be different for each creative work, but such a decision is not possible in traditional visual art with "original". This is the essential difference from digital media creations . In digital media, each so-called copy is identical to the so-called original. The concept of originality does not apply in digital works. Each copy is like every other copy, both an original and not an original. Thus, an artist using digital media may choose to produce work for galleries, or mass media work that can be collected, but in reality this choice does not exist.

Currently, artists who create work in mass media can choose to make their work available through galleries, or publish their work for free and make it available online. To be sure, there have been many initiatives over the past 20 years that have offered a third option, but they have either failed in succession or have not had widespread impact. I think these setbacks are based on the inability to develop the collector base, which is partly a platform issue, the existing technology doesn't support what people want. If the platform does grow, and it cultivates a group of collectors, is it possible for an artist to work in both ways? Can an artist successfully play the gallery game and produce economically acceptable work for a larger audience? Can an artist avoid galleries entirely, only do digital mass media work, and still support himself?

The social and emotional shifts people need to start collecting digital art, just like they collect music, feels like the hard part, and the technical side is now possible. One way of managing it is blockchain , a set of technologies that are often hyped and misunderstood. In the simplest case, a blockchain is a list. A blockchain innovation is the way transactions are verified so they are considered accurate. The blockchain is open, anyone can read it, it is decentralized, so everyone can access the material. Blockchain is the key to moving away from licenses to digital media properties because the information is accurate and decentralized. In addition, the blockchain can record the transaction history of loans and sales of works. The provenance of the work is public and guaranteed to be accurate; it cannot be falsified.

For example, an artist might decide to publish a digital photograph for collection. This photo can be a unique piece or there can be any number of versions. The process starts with entering information about the work: title, medium, size, year, edition size, etc. This information, along with the unique essence of the photo archive, is recorded on the blockchain. This "unique essence" is called a hash, or more colloquially, a digital fingerprint. At this point, the photographic record exists as a negotiable property. If you decide to release 10 versions, there are 10 unique properties. If it is decided to release a 2000 edition, there are 2000 unique properties. As a creator, an artist can transfer ownership to someone as a gift or to the person who bought it. This transaction does not need to be done in person or "by hand". Software can automate this through a website or app, or an authorized agent can handle these transactions. Once the change of ownership is recorded on the blockchain, the new owner has all the rights to sell, loan, etc.

To be clear, the archive itself, the artwork, can be copied and shared with others outside the blockchain. Blockchain has nothing to do with copy protection or digital rights management (DRM). The blockchain tracks transactions, but it does not limit the processing of files; that is up to the owner. For example, if someone sells a digital photo and the transfer of ownership is recorded on the blockchain, the original owner loses ownership, but he can keep a copy of the file (there are ways to change this, but this is not the same as the block chain is separate). The new owner can do whatever he wants with the archive, including copying and distributing those copies as many times as he wants. The person who owns these copies is not the owner of the work.

This is a new way of owning that requires a mindset shift. One way of thinking about this is similar to how copyright works. Imagine that a poem is copyrighted. Anyone can get the poem from a library book or via the internet, but only the owner has the right to approve distribution, among other things. In the case of a photo, someone else may have a copy of the photo, but they do not own the image.

a fork in the road

Digital media collections may develop in two broad ways. One direction is to reflect the existing art world by selling something unique or exclusive. This is the traditional, conservative model of selling digital media archives as unique works of art or limited editions, perhaps at high prices for unique, or digital artifacts with only a few hundred editions. Before this kind of thinking, the market for high-end prints, including editions of lithographs and etchings, made them more affordable than unique paintings and drawings. Many examples of this digital media sales model are being developed by individual artist and venture capital sponsored programs. It could be a great business model if successful, but it's not transformative for artists, art or society. It may expand the possibilities for more people to collect art, especially digital art, but it is still exclusive. While there is promise of success with this model, which will support artists, there is another opportunity.

The unique material of digital media offers a new collection opportunity that was not possible in previous forms of visual art. This is only possible on digital media because there are no originals and all copies look the same. As a hybrid between unique objects and unique qualities of digital objects, each "identical" digital copy can have a unique, verifiable digital signature. Therefore, each version is interchangeable in appearance and performance, but each version is singular. Each version can be registered, bought, sold, loaned, and traded as a unique object; importantly, each version can be accurately verified. This underpins a new model of collecting digital media, in which one edition can be sold in bulk at a lower cost, or a large number of unique works can be managed, but each edition still includes traditional ownership. For example, version 132/500 or version 5243/20000 can be purchased, recorded and verified. In a different direction, the artist can produce any number of unique pieces in a series. Using an old concept from the photography world, imagine that each image on a contact sheet could be sold as a unique piece. Or, more likely, a set of images edited from several rolls of film. The computation that does this is prohibitive in analog media, but digital media can fully support it. As another example, imagine a software body that can generate images. Each image can serve as a series of unique works, rather than the more traditional mode of editing only one of the archives.

There are other unique elements to collecting digital media that were not possible until recently. Finally, to compare music, what makes it possible to collect music on records and tapes is the accessibility of playback hardware. In order to collect this media, there needs to be a way to experience it. For example, turntables range from inexpensive models to fancy devices for audiophiles, but it is possible to listen to vinyl records on a personal, family or community scale. When the record collection started, digital media didn't exist yet. It's only in the past few decades that digital media playback hardware has become readily available and of a quality high enough to attract legions of artists to create for it. More recently, with the development of ultra-thin, high-resolution flat screens and more powerful home media players, including video game systems and hardware embedded directly into TVs, there has been a positive shift in hardware for playing digital media files. Now, millions of people have easy access to digital media files over the Internet to experience on their phones, tablets, and newer TVs. In addition to the devices people already own, there are a growing number of hardware makers specifically designing screens to display digital art.

To have broad impact, new modes of collecting media art will need to be very convenient . It needs to be broadly across cultures, incomes and ages; it needs to be accessible to millions of people. This new model will require decentralization . It must support different groups in curating and selling works without centralized control. The private "store" system created by contemporary tech giants is the exact opposite of what is needed. Individuals and small groups should be able to create their own "gallery" or "tags", and individual artists should have the freedom to directly publish and control their work.

As long as artists continue to live in a capitalist economy, a new form of digital media collecting will require financial support for participating artists. Publishing work online without getting paid is still an option for artists, but there should be an alternative for those who want to pursue pay. The entrenched gallery system does not support this kind of work, and there are too few supporting models for finding grants, fellowships and commissions for digital work. Likewise, some artists have found success on different crowdsourcing platforms, but these systems and audiences prefer narrow practices and discriminations. Artists who create digital media don't have enough opportunities to support themselves with their work.

Dematerialization of artwork

Today, while art is still associated with wealth and traditional media, as early as the twentieth century, art’s requirements for both have disintegrated. It's safe to say that an object's status as art has nothing to do with scarcity, cost, or raw materials. Now is the time to continue work that began decades ago. Artists have long used mass media and explored new materials. For example, more than 50 years have passed since On Kawara started the "I got up" series by sending postcards explaining his daily wake-up time; since Felix Gonzalez-Torres -Torres) for his Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA), it has also been 27 years since he placed a pile of candy in the corner for museum-goers; Dada, The spirit and legacy of Fluxus and Net Art still applies today.

Now is the time to build on these concepts, rather than going backwards, or relying on patronage and exclusionary power relationships. In the future, a native digital media collecting ecosystem may be completely different from the current art market, but this new way of collecting may not affect the existing market. The current art market is a niche market that will continue to develop, but not always in this direction. If a new model succeeds, it will form a new field.

original source

In addition to sharing Taiwanese NFT projects on Matters, c2x3 also appears on Facebook , as well as English versions of Twitter and Medium , and is committed to promoting Taiwanese projects to the world! If you like our content, we sincerely invite you to share our articles for more people to see! c2x3 stepped down and bowed~

Like my work?

Don't forget to support or like, so I know you are with me..

Comment…